Each autumn, the pictures return. Mist hangs over the bracken, dawn light glows orange, and in the centre a stag, antlers catching the first rays or head tilted back in a roar. In autumn, the deer in the city parks come into breeding condition, a period known as the rut or rutting season. Their movement increases, and rivalries surface. The local press runs this story year after year, and national outlets, if they pick it up, do much the same. A quick look online at coverage from the last few years shows the pattern repeating: Richmond Park, or another city park, is almost always pictured with a single stag, tightly framed, the background blurred or cropped away.

These long-lens photographs used and re-used may bring drama, but little sense of place. In those pictures, the animal usually stands alone, fog wrapped around it, as if announcing the season. It is easy to see why such images dominate: the antlers of the stag are spectacular. It is all very photogenic. The scene is almost ready-made for the familiar story. Incidentally, I typed “deer” into a popular stock-image site and the results showed a similar approach: endless antlers and heroic poses at the top, while pictures of the herd slip far down the list. But what preconceptions or assumptions do these images carry? A caricature of nature, or simply the kind of seasonal human-interest story the papers favour?

Long lenses

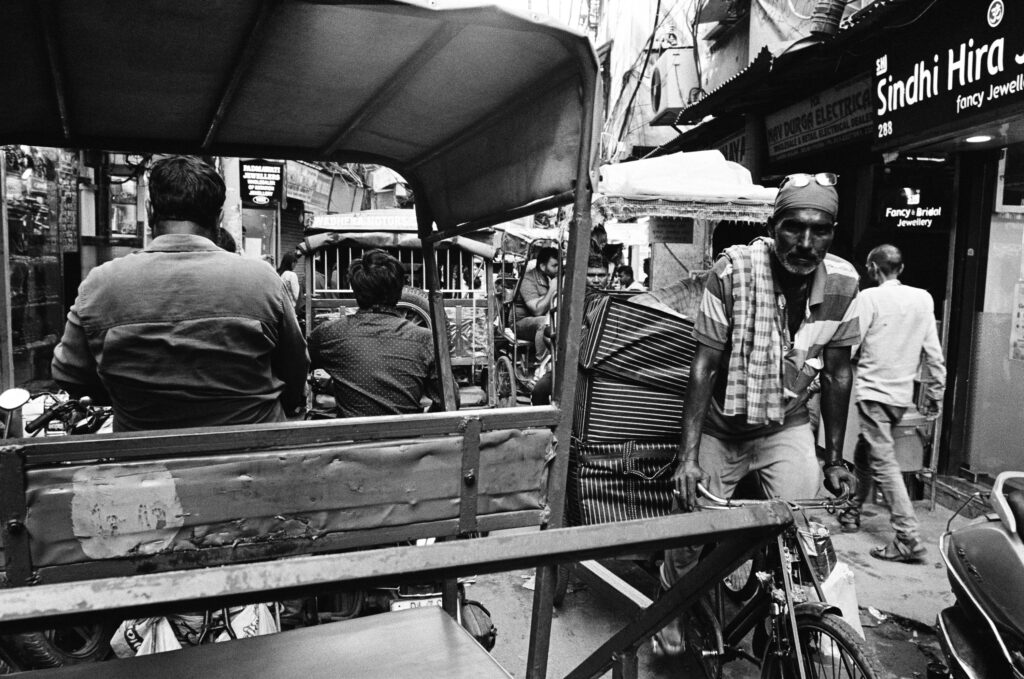

Although I mainly used longer lenses to keep a safe distance and avoid disturbing the animals, I tried to counteract the inherent visual compression created by a long lens by framing in a more “spacious” way. Some of the resulting photographs, therefore, include hinds, other animals, people, vehicles, and even glimpses of the city in the background, the latter an important detail as the park is, after all, a space surrounded by the urban sprawl of London. The pictures in this article were mostly taken at dawn or early morning.

My approach was to let the environment shape the frame, rather than narrowing in on a single “hero” subject. I wanted the photographs to show more of the park’s complexity: the herds, the people passing through, and the details. Often, that meant simply “adding space” so that different presences could share the image.

The photograph that opens this article reflects that choice. A stag lies in the grass while a passer-by, earphones in, walks on. They occupy the same ground but remain separate, as if two worlds overlap without noticing each other. That, too, is part of the story of the parks. A few centuries ago, these were hunting grounds reserved for the nobility. Later, the parks were democratised and opened to everyone.

Antlers In The Fog, Power In The Air

Once you notice how often stags are chosen to dominate the frame in their conventional portrayal you realise that assumptions must be at play: nature is presented as a performance, with stags in the lead and the rest of the herd in the background. The stag posture is supposed to be read as noble and powerful, but also lustful and aggressive. In people, these traits might make us uneasy, yet in animals they seem to entertain. This type of depiction is, therefore, incomplete. The rut is more than a duel of dominance. Females are actively shaping the story too: they watch, move, and choose mates, yet are seldom given the visual space to show agency.

Power seems to direct the usual story, pulling some things into the spotlight while letting others fade to the margins.

Awareness of this hierarchy helped me avoid the default framing.

Avoiding A “Telenovela” Version Of Nature

There is, therefore, a “telenovela” quality to how the animals and the park are conventionally portrayed during the rut. I use the word “telenovela” as shorthand for high drama, predictable emotion, and neatly drawn characters. The drama comes with fog and antlers: the powerful stag and the clashes for dominance. To avoid the cliché of a lone stag in mist, I sought to photograph female deer in alert poses, or the herd moving through the park in collective moments of interaction, framed to show both space and relationships.

The Dangers Of Spreading The Approach To Science

As I was thinking about the conventional reporting of the rutting season, i.e. the “telenovela” of fog, antlers, and lone stags, it became clear to me how these usual images may be simply reflecting assumptions about nature. What happens once a year to the roughly 600 deer in Richmond Park might seem trivial, yet the striking thing is that the same desire for drama that seems to shape those stories may also appear unwittingly in scientific practice, influencing what is studied, collected, and preserved.

A 2019 study by the Natural History Museum in London (details are easily found online) examined over two million specimens from global collections and revealed a significant bias. The study found a persistent male skew: only 25% of bird type specimens and 39% of mammal type specimens were female, with broader collections still biased (about 40% of birds and 48% of mammals female). More visually impressive examples (brightly coloured plumage, etc.) were more likely to be collected, reflecting assumptions about what is deemed important. In an echo of the patterns I saw in media coverage of the rutting season in the city parks, the attention placed on the male animals becomes the default, associated with power and dominance. Images and specimens that emphasise drama, size, or conflict are rewarded by publication. Both the photographer framing a “heroic” stag and the scientist selecting striking specimens for a collection may unconsciously be responding to similar aesthetic and cultural biases.

This has consequences. Research built on skewed collections risks flawed conclusions. What might be harmless in a local newspaper article is, on the contrary, very significant when science repeats the same unconscious biases. The pattern tells us more about ingrained cultural assumptions than about the animals.

Framing A Managed Wilderness

In Richmond Park, the word “wild” needs qualification. The deer in it are not tame. They roam freely and live by their own rhythms. They are, however, part of a managed ecosystem. It is a landscape curated to seem wild. Bracken is cut back, paths are maintained, herds are counted, and numbers culled.

Richmond Park is home to two species of deer: red deer and fallow deer. Red deer are the largest land mammals in the UK. Males, or stags, grow thick necks and large, pointed antlers; females, or hinds, are slender and have no antlers. Fallow deer are smaller animals. Bucks have flattened, palm-like antlers, while does are similarly slender and lack antlers. Male antlers are central to the seasonal display, while females remain less conspicuous.

Both species follow similar annual cycles. In spring, males grow antlers covered in velvet. Females give birth in summer. Velvet is shed in late summer as antlers harden for the rut, when males compete for mates. Red stags roar and fight, fallow bucks groan and display. Winter is the gestation period.

Venison And Leather: Life And Death Under Management

Information about the deer culls carried out in Richmond Park and other Royal Parks can be found online from local media, websites of interest groups, and the posting of responses to Freedom of Information requests. In Richmond Park, roughly one-third of the herd is culled each year, with males in late winter and females in November. Venison and leather goods are produced from the culls.

This practice, once unremarkable, seems to be drawing more public scrutiny as questions of transparency and ethics rise alongside awareness of how management is carried out.

The Dance Of The Observer And The Observed

Seeing is never neutral. How we look at the world is shaped by habits, assumptions, and often by ideas of power. Attention tends to fall on certain details while other elements are overlooked. In order to see Richmond Park more fully, that “telenovela” must be left behind, so that we can notice the herd, the landscape, and the features of the season.

In my photographs, I looked for what is often left at the edges: the urban environment, the bracken, the canopy, the people and vehicles passing through, and the deer that rarely take centre stage. Taken together, my 36 Views of Richmond Park aim to offer a wider frame on what it means to see, for myself, a managed wildness at the edge of the city.

Share this post:

Comments

Alastair Bell on Beyond the Fog: 36 Views of Richmond Park

Comment posted: 01/10/2025

Superbly done.

Comment posted: 01/10/2025

Thomas Wolstenholme on Beyond the Fog: 36 Views of Richmond Park

Comment posted: 01/10/2025

Comment posted: 01/10/2025

Ibraar Hussain on Beyond the Fog: 36 Views of Richmond Park

Comment posted: 01/10/2025

Enjoyed this essay - as being very familiar with Richmond Park over the decades. You’ve really got some fantastic photos !

The deer have been there since the park was made, at the time and I guess as well as now they're the property of the King.

I can’t help but notice the confusion between using science and scientist and conflating them with each other.

Scientists aren’t science - so their opinions aren’t science. Males in the animal kingdom are generally more impressive than females. It’s just a fact of nature. If we were still cave dwellers; hunting and gathering, I’m sure an alien observer would find the Men more impressive with their stature, size, long hair, beards and hairy bodies, than the females.

So naturally any photographer; male or female, will want to photograph a brightly coloured peacock rather than a peahen.

Comment posted: 01/10/2025

Comment posted: 01/10/2025

Eric Rose on Beyond the Fog: 36 Views of Richmond Park

Comment posted: 01/10/2025

Comment posted: 01/10/2025

Gary Smith on Beyond the Fog: 36 Views of Richmond Park

Comment posted: 01/10/2025

Interesting to an old guy in the States!

Comment posted: 01/10/2025

Comment posted: 01/10/2025