This is a near-full rewrite of an article that was originally shared on Casual Photophile in August 2024. In addition to tweaking some content, I also wanted to correct a technical error and address some formatting issues that arose during publication. This revision is also posted at the author’s personal website.

You can follow me on Bluesky and/or Mastodon for reasonably-frequent street photos.

In 2016, I bought a camera, two lenses, and a bag full of accessories that completely changed my relationship with photography.

At the time, I was on a rangefinder kick (via the Leica M6 TTL and Minolta CLE) and had also been dabbling with medium format (using a Mamiya 645, Bronica SQ-A, and a motley assortment of others) on the side.

Within a year, everything else was gone. In the near-decade since, I’ve occasionally tried to get back into “regular” 3:2 shooting through various compacts, but none of them had any staying power. I liked some of them conceptually, sure, but…

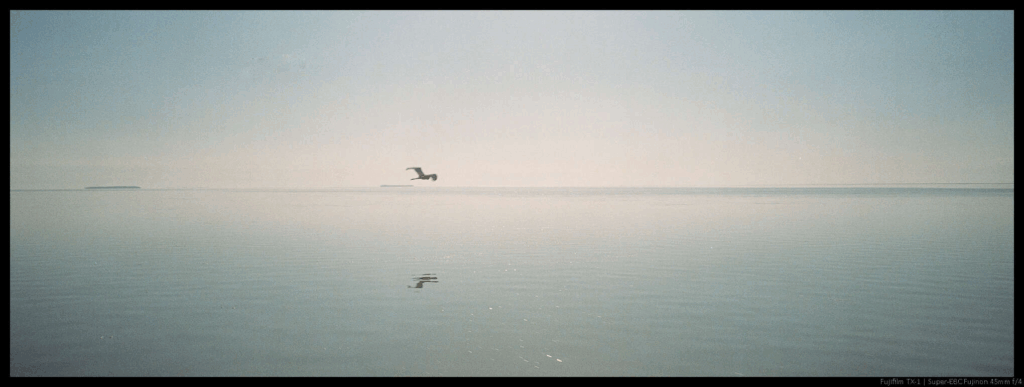

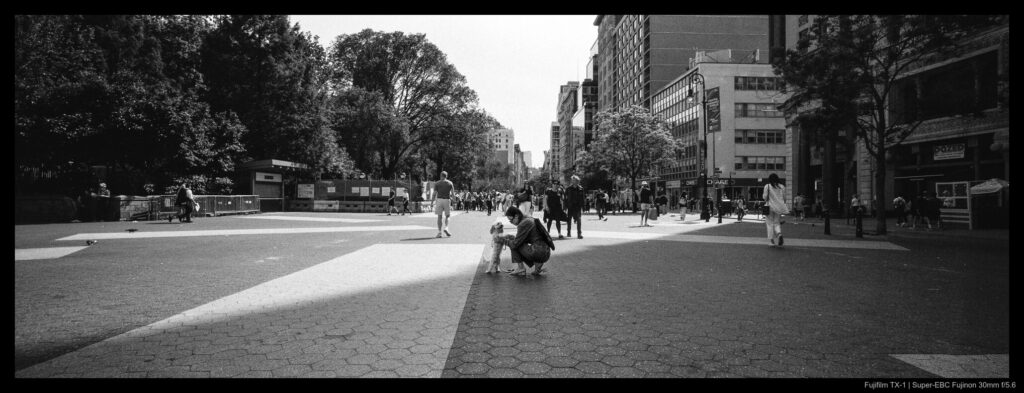

…I was too hooked on the Fujifilm TX-1, a 35mm rangefinder with the unique ability to natively shoot panoramas.

No tricks.

No gimmicks.

No frills.

The Fujifilm TX-1 (also sold by Hasselblad as the X-PAN) is a device designed with singular purpose: to capture “true” panoramic images on 135 film without wasting a millimeter of space or an ounce of material. Despite its quirks and a handful of shortcomings, it executes in a way that no camera has before or since.

It’s a camera that has acquired a strange and near-mythical status since its launch in 1998. It’s a reputation that makes objective discussion difficult– and no amount of poetic prose about the artistic merit of panoramas can (or should) change the very real need to be rational when looking at the eye-watering prices these command on the used market.

There’s no way to get into this system on the cheap, and the supply is only dwindling as turn-of-the-century electronics age and wear.

I’ve run just shy of 2,000 frames (or a bit more than 130m of film by length) through this camera as of November 2025. At this point, it’s the only camera I shoot with (film or digital) with any degree of regularity– the only one that lets me feel as though I’m seeing and depicting the world with both eyes open.

In theory

Format

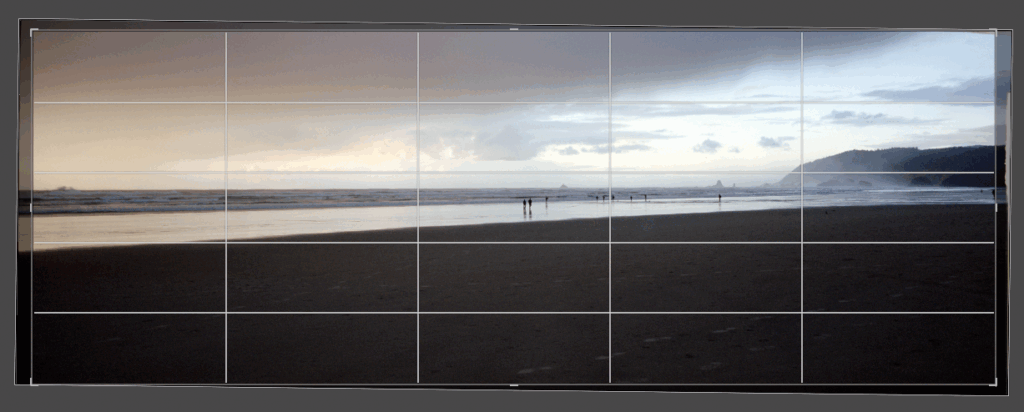

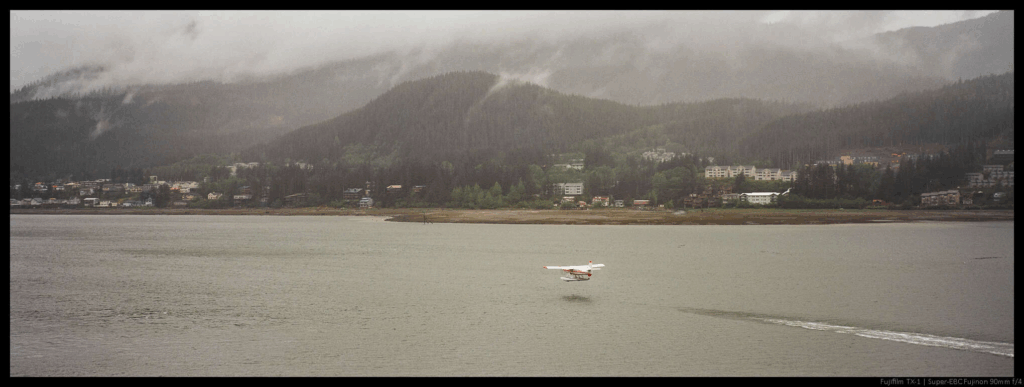

Exposing 65x24mm of 135 film at a time, the Fujifilm TX-1 lives in the space between “small” and “medium” formats. The resulting images have an aspect ratio of approximately 2.74:1, making 16:9 (1.77:1) and even 6×12 (2:1) look tame. The camera’s extra-wide internal mask means that every frame is captured in one take from edge to edge.

By comparison, most other “panoramic” cameras either crop a standard 36x24mm area using retractable gates or physically swing a lens from side to side. Although these approaches have their merits, the first sacrifices usable film area, and the second introduces both geometric (objects and lines appear slightly warped) and chronological (laterally-moving objects blur due to lens motion) distortion.

The three system lenses– the Super-EBC Fujinon 45/4, 90/4, and 30/5.6– were designed to throw an image circle only slightly smaller than those used by 6×7 cameras (67x56mm). Although the lenses are somewhat slow for a 135 camera, this allows them to remain compact while still enabling panoramic coverage.

system field of view (FOV) comparison

| Lens | Horizontal | Vertical | Diagonal |

|---|---|---|---|

| 30/5.6 | 94.6° (61.9°) | 43.6° (43.6°) | 98.2° (71.6°) |

| 45/4 | 71.7° (43.6°) | 29.9° (29.9°) | 75.2° (51.4°) |

| 90/4 | 39.7° (22.6°) | 15.2° (15.2°) | 42.1° (27.0°) |

65x24mm FOV (36x24mm FOV)

At any given time, the camera can be switched between panoramic and normal modes. Both formats can be mixed and matched on the same roll without needing to load/unload film.

Physical

The camera used in these photos is my personal camera and has a spirit level slotted into the hotshoe and strap anchors threaded through the strap lugs. These are not natively part of the camera system.

The Fujifilm TX-1 is large for a camera that uses 135 film, but is far more compact than most medium format cameras (save for folders, depending on how you evaluate size). Sporting a smart two-tone look from its titanium/champagne finish and black rubberized (or wooden) grip, at first glance it looks like a slightly-stretched 135 rangefinder.

A standard 135 cassette measures roughly 32mm in diameter and 50.8mm in height; the Fujifilm TX-1 body measures 166mm long by 51mm wide and 82mm high.

A typical ~350mL (12oz) canned drink has a mass of around ~380g (give or take some– based on beverages in the United States); the Fujifilm TX-1 body has a mass of ~720g (not including batteries, accessories, or material variance).

While small for “medium format” glass, the lenses have some heft to them.

system mass

| Component | Mass |

|---|---|

| Body | 720g |

| 30/5.6 | 298g |

| 45/4 | 222g |

| 90/4 |

Mass without accessories, film, or battery

The 30/5.6 and 90/4 both move the camera’s center of gravity considerably forwards when mounted. With the 45/4 attached, the camera can be balanced on its bottom and remains surprisingly compact.

Even the 30/5.6 doesn’t add too much in the way of bulk (though using the rare lens hood changes this quite a bit). While the camera becomes a bit more front-heavy, it won’t tip without a push (albeit only a small one).

The 90/4, on the other hand, dramatically increases the overall amount of space the camera occupies, making for an ungainly ‘T’ shape that can be awkward to stow or carry.

Controls

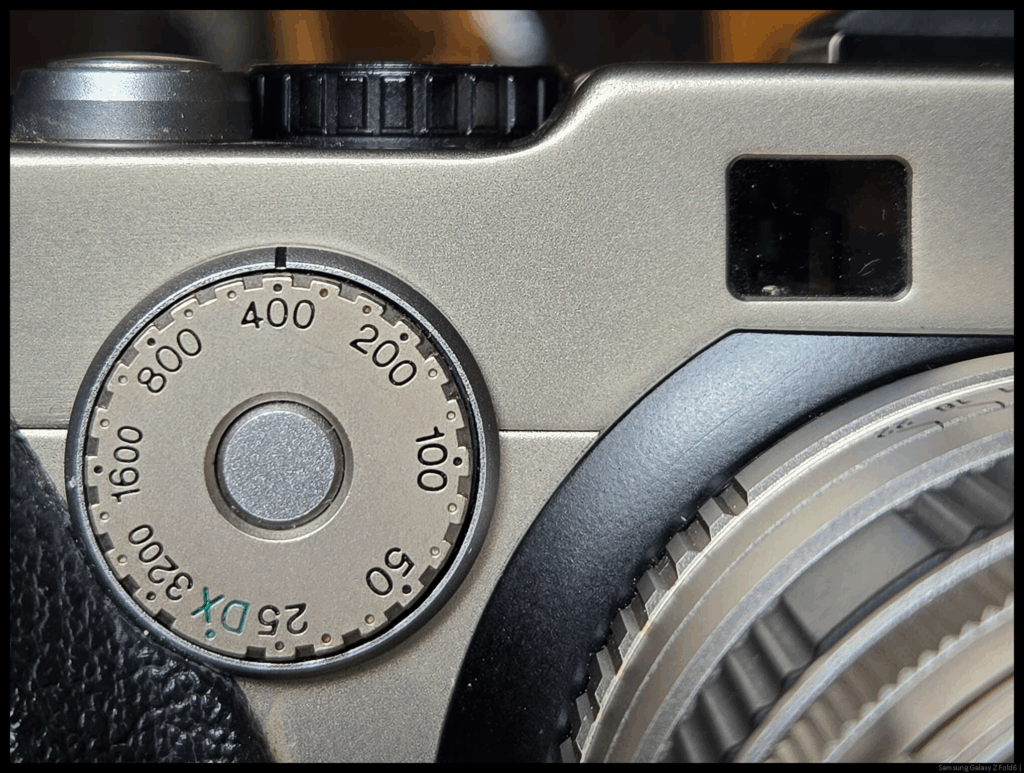

The Fujifilm TX-1’s controls are granular enough to handle a wide variety of shooting conditions. Most inputs are situated along the right-hand side of the top deck, with some auxiliary features accessed via buttons on the back plate. The ISO selector is the sole exception, and is located between the lens mount and hand grip.

This dial locks when set to DX (automatic ISO detection for compatible cassettes), and is released by pressing the center button.

Aperture is set on the mounted lens itself using a frontal ring. These have half-stop detents, with no tactile difference between half- and full-stops.

Shutter speed, power/drive mode, and exposure compensation controls are clustered on the right-hand side of the top deck, along with the shutter release itself. The shutter dial locks when set to [ A ] (aperture priority), and is released by pressing the center button. Speeds can be set in full stops from 8s through 1/1000s (along with a Bulb setting).

The shutter release has a halfway detent that activates the meter.

Drive mode (and the fixed, 10s self-timer) are set by moving a rotary switch that surrounds the exposure compensation controls. Exposure compensation can be set from -2 to +2 by twisting the textured dial.

An ordinary hotshoe sits near the center of the camera. As marked on the shutter speed dial, the camera’s flash sync speed is 1/125s.

When the camera is powered on, a small LCD displays the remaining number of shots based on the current film format. This screen dynamically updates after an exposure or when the shooting format is switched.

The back of the camera hosts a locking rotary switch near the viewfinder that toggles the current image format (between panoramic and 3:2), as well as a larger LCD that reads out basic information and battery status. Beneath the screen are buttons for AEB, illumination, and manual rewind (recessed).

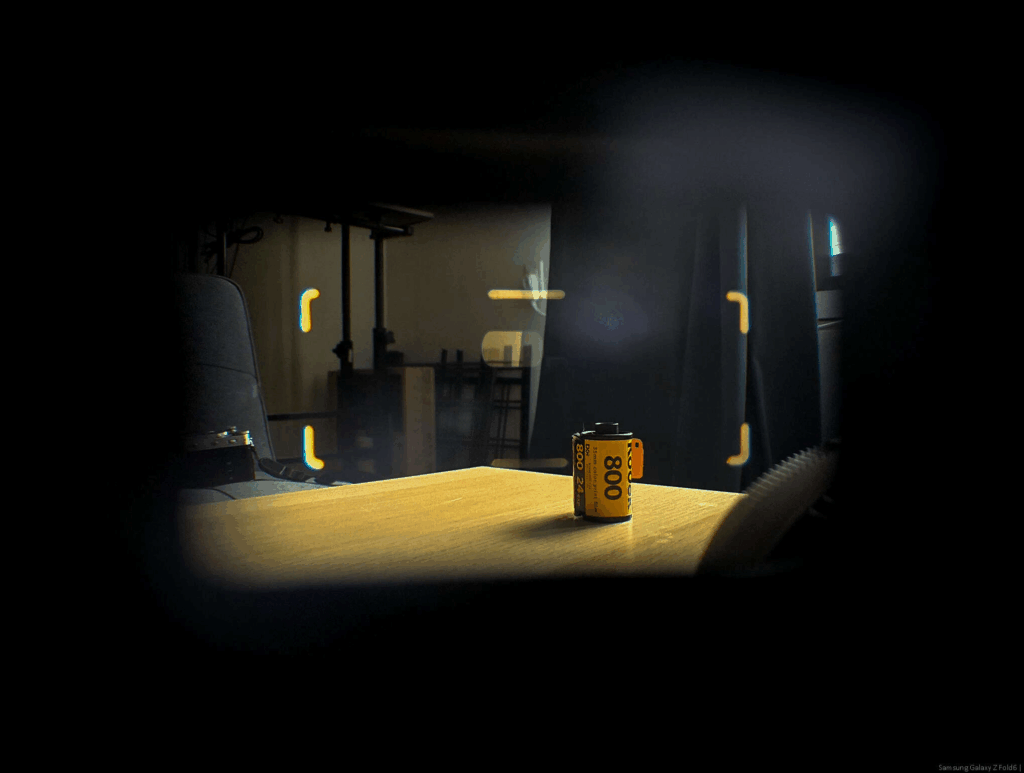

A cutout window on the left-hand side shows the label of the currently loaded film cassette.

The left side of the camera has a flip-up latch that opens the back door.

Viewfinder

Viewfinders are among the most essential parts of a camera, and the classic brightline/split-image one on the Fujifilm TX-1 is well-engineered. Framelines (illuminated by a dedicated frosted window on the front plate) are bright and visible under most lighting conditions, and are keyed to the 45/4 and 90/4 lenses. Only one set of framelines is visible at any given time.

The rangefinder patch is bright and clear, manifesting as a yellow-tinted rectangular oval roughly in the center of view.

The meter display is centered near the bottom of the viewfinder, with fairly typical – ● + lights that illuminate to indicate underexposure (-), correct exposure (●), and overexposure (+). The +/- lights will flash if the center-weighted meter detects significant over/under exposure.

Framelines

The 45/4 framelines come close to the edge of the viewfinder, and are only slightly occluded by the lens itself.

The 90/4 framelines are much smaller, and remain unobstructed despite the lens’ much larger visual footprint.

The 30/5.6 is designed for use with an external hotshoe-mounted viewfinder, and keys up the 45/4 framelines in-camera. Its field of view is wider than the internal finder can show at any eye distance.

filters

All three lenses are threaded to accept standard filters.

| Lens | Filter size |

|---|---|

| 30/5.6 | 58mm |

| 45/4 | 49mm |

| 90/4 | 49mm |

Fujifilm specifically produced special ND filters that darkened the center of the frame in order to reduce perceivable vignetting. These filters were rated for about a stop of light loss, effectively reducing the light-gathering speed of the lenses to f/5.6 and f/8.

These first-party filters can be found online, but as with everything else they carry a hefty price.

In practice

Composing

Identifying and framing a scene is the start of the creative process. The Fujifilm TX-1’s extreme aspect ratio can make this challenging, as many compositions that work in 3:2, 4:3, or 1:1 are very lopsided in a 2.74:1 panorama.

In addition to potentially picking up visual clutter around the frame edges, the format also significantly exaggerates perspective and tilt. Although software can correct for these to some extent, both cropping and geometric distortion rapidly chew up valuable image area.

In general, I find the Fujifilm TX-1’s viewfinder to be more than up to the task. Bright, clear, and expansive, there’s enough room outside both the 45mm and 90mm framelines to maintain awareness of what’s just out of frame and work accordingly (though wearing glasses reduces peripheral vision by a fair bit). Parallax is only pronounced at close focus, and can generally be ignored.

There are two notable omissions.

First, there is no readout of the selected shutter speed, manual or otherwise. If you lose track of what is dialed in or are using aperture priority, you simply have to guess as to what shutter speed the camera will use (the TX-2 / XPAN II remedy this deficiency).

Second, there is no way to ensure that the camera is level in the finder. Because of the format’s proclivity towards distortion, a horizontal horizon guide (or spirit level) would be extremely useful. I use a hotshoe mounted level when shooting from the waist, but most of the time you simply have to eyeball it.

Compositional considerations

There are no hard and fast rules in photography, but I wanted to take a moment to list some of the common trends that surfaced while I was choosing sample photos. I’ve tried to keep these focused on points that work particularly well in panoramic compositions.

Take these as suggestions and starting points rather than as any kind of written law– especially given how much of art is subjective.

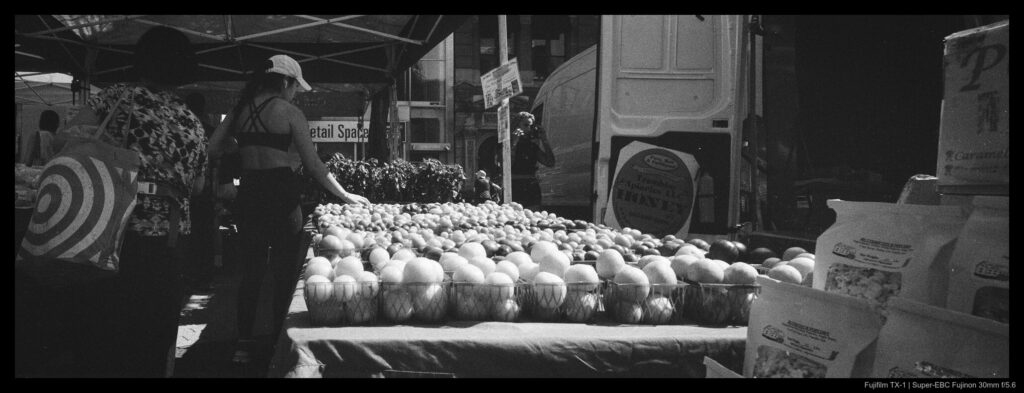

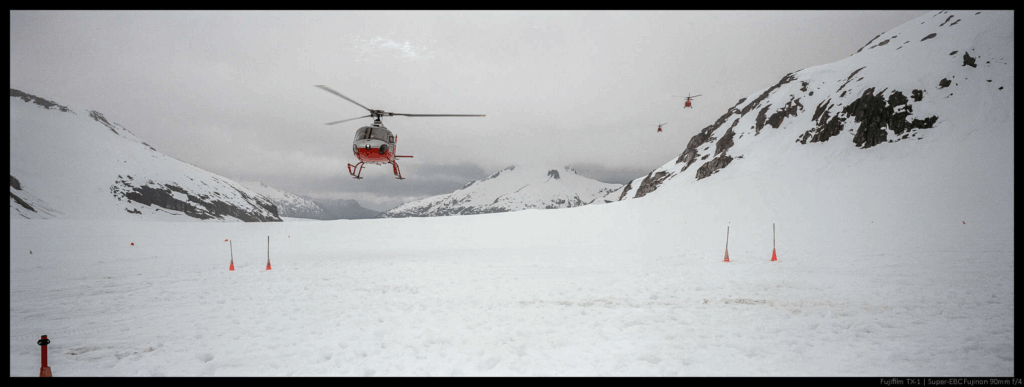

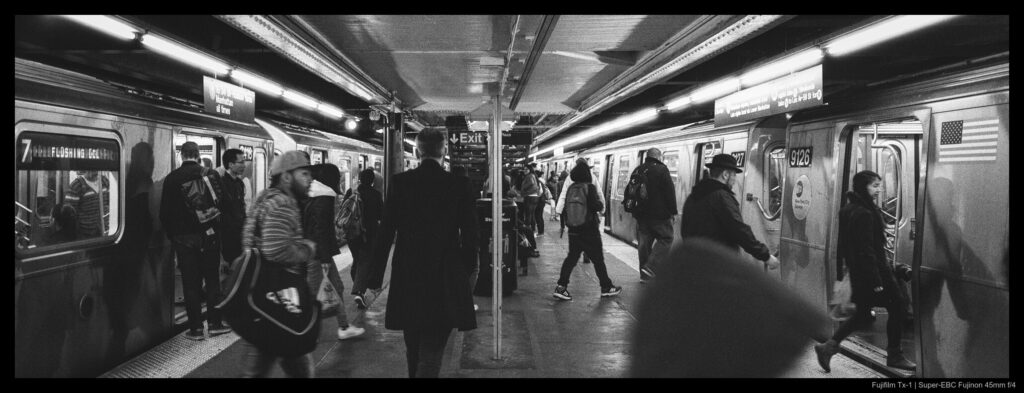

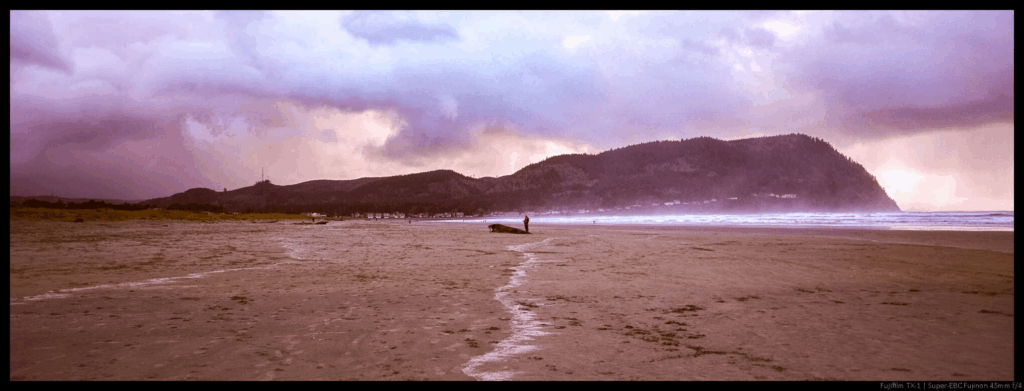

Shots with long, sweeping lines that traverse the length of the frame work well in this format.

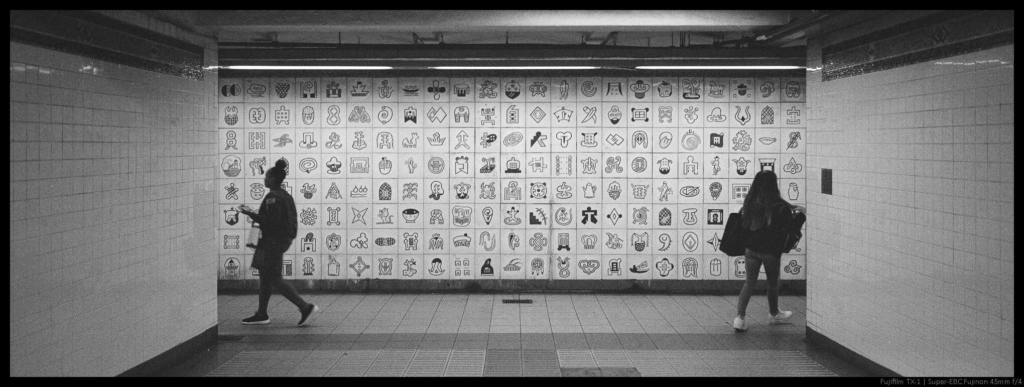

Repeated patterns have time to go through several iterations when arranged along the long dimension.

Emphasized tilt and perspective can be used for dramatic effect.

Leading lines have ample room to breathe and draw the eye through areas of interest.

Balancing subjects on opposite sides of the image can take advantage of increased negative space.

Even when subjects are of different “weight”, lateral division is still compelling.

Some subjects don’t need to be counterbalanced, especially if there is an implicit (or explicit) directional element to the shot.

Centered compositions can take full advantage of the subject being isolated along one axis while not being lost along the other.

These can also be used to emphasize a vanishing point.

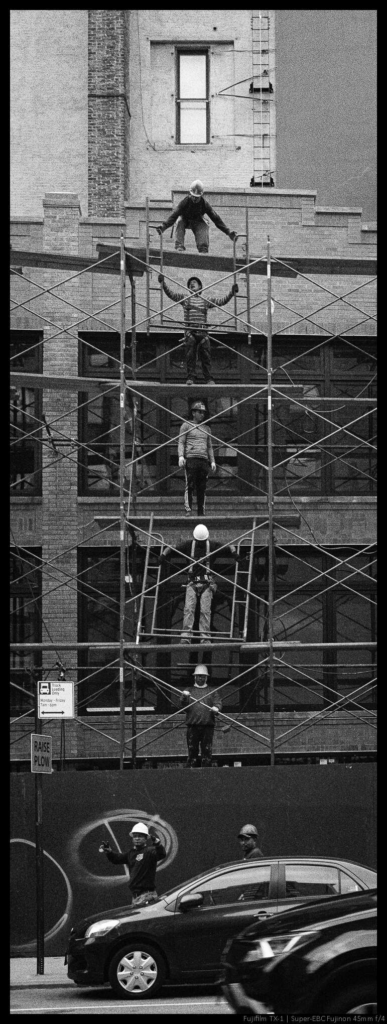

Although opportunities for vertical photos are comparatively rare and more technically challenging, they are still worth looking for.

“Seeing” the world through the Fujifilm TX-1 is a matter of adjusting mental perspective more than anything else; with both eyes open, our view is already panoramic by default. If anything, the more “classical” formats are less like our natural vision, not more.

The challenge of shooting wide frames is distributing interest throughout a picture that can be inspected at the viewer’s leisure. Under most circumstances, we see far less detail in our peripheral vision, meaning that distractions get filtered out by dint of being less clear. This is not true with a still image, so other techniques (both in-camera and in post) are needed to manage the viewer’s perception.

Practice and persistence pay off; familiarity with the style makes it easier to recognize compositional opportunities in everyday life.

Such being said, I’ve perhaps gone too far off the deep end and now have trouble with squarer formats (though I still adore 1:1).

Operation

Deciding on a composition is only part of the creative process– actual execution is just as important. At the most basic level, a camera must be good enough to enable its operator to take their desired shot, be that a portrait or a freeze-frame action moment. Absolute image quality means nothing if the photographer can’t get the shot in the first place.

I’ve heard it said that the most boring thing you can do with a Fujifilm TX-1 is to take landscape photos with it. I don’t think that’s entirely fair, but people definitely pigeonhole this camera into that role when it is quick and responsive enough to handle a variety of circumstances.

With both shutter speed and aperture controls being large and well detented, exposure parameters can be changed by touch while still being easy to set by eye. This is important given the lack of in-finder information: if you’re in a hurry to ready the camera, counting clicks may be all that you have time to do.

Ideally, you want to be able to keep track of both the currently set values and the direction in which the various inputs rotate. This is broadly true of any camera, but it’s a bigger issue when there are no indicators or warnings at the moment of capture other than a rough meter warning.

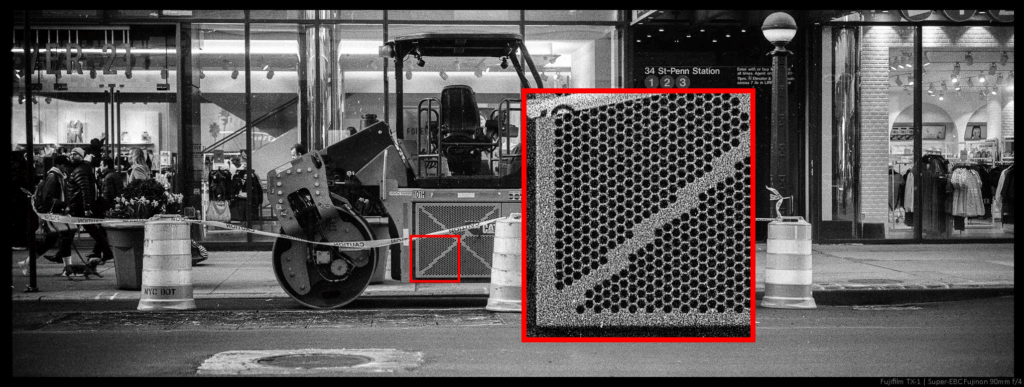

Speed of operation primarily depends on your skill with rangefinder focusing. With a long base length, the Fujifilm TX-1’s rangefinder is very accurate, enabling precise focus with even the long 90/4. If resolution is important to you, know that you can wring every last drop of it from the glass even in the field.

The rangefinder patch works as expected: rotating the lens barrel guides the doubled image in the same direction as the top of the lens (clockwise racks in the focus point, counterclockwise pushes it out).

When shooting with the wider lenses (especially the 30/5.6), the stellar optics and deep depth of field enable similarly excellent results.

Both precise and zone focus are viable. With the 45/4 and 90/4, I prefer using the rangefinder; with the 30/5.6, zone focus is usually safe enough, at least on a sunny day.

Ultimately, I’m simply not very good at estimating distance, and so I avoid it unless I’m certain that even I can’t mess things up. For people who are better at this, the table below provides the various hyperfocal figures (taken from a calculator; the scales printed on the lenses may differ).

hyperfocal settings at f/16

| Lens | Hyperfocal distance | Hyperfocal near limit |

|---|---|---|

| 30/5.6 | 1.13m | .57m |

| 45/4 | 2.52m | 1.26m |

| 90/4 | 9.98m | 4.99m |

Assuming a .03mm circle of confusion (CoC)

If you prefer to go without a lens hood (or simply don’t want to buy one at an exorbitant price), be wary when using the 45/4 and 30/5.6 as these lenses catch stray fingers very easily. While you can sometimes fix this in a black and white image, it’s a pain at the best of times.

The 90/4 is substantially longer and much less prone to this issue, even without using a hood (which is the same between the 45/4 and 90/4).

The shutter release has two clearly-defined stages, making it easy to take a meter reading (with a half-press) without accidentally triggering a shot. The button itself is not threaded, but there is a port on the camera for a cable release if you so desire.

Noise-wise, the shutter is not especially loud, but is certainly not silent. The motorized film wind is surprisingly quick considering the amount of film that has to be transported between exposures, and is of a similar volume as the shutter mechanism. The camera is definitely audible in a quiet room, but is much less noticeable outside.

Delay-wise, the shutter responds quickly enough to capture typical moving subjects (such as cars and people) without much trouble. Higher-speed animals or motions are harder to nail, but at the very least there’s no reflex mirror to increase shutter lag.

The Fujifilm TX-1 is heavy enough with any of the mounted lenses to merit a wrist or neck strap. If I’m primarily expecting to use the 45/4 or 90/4, I’ll use a wrist strap and carry the camera in hand– though this does eventually start to strain your wrist.

When using the 30/5.6, I tend to use a neck strap so that the camera can hang by my waist. Worn like this, I can glance down to check the hotshoe level, then fire knowing that most of what’s in front of me will be recorded. As a bonus, this helps avoid what I’ve heard referred to as “six-foot syndrome”: the tendency for photos to be shot from the same eye-level perspective regardless of circumstance.

Routine tasks

Loading the camera is simple: open the back door by flipping up a latch on the left-hand side, swing the back door open, then slot in a 135 cassette in the usual place. Pull the leader towards the take-up spool until the tip is just short of the right-hand side of the chamber, then close the back.

If done correctly, the camera will then wind the full roll onto the take-up spool, then show the number of exposures you have. At that point, you’re ready to roll. In the event that the winder was unable to engage the loaded film, the top LCD will remain blank and you’ll have to try again.

As a bonus, this means there’s never any uncertainty as to if the camera is loaded or not. If the LCD is blank or reads “E”, you’re safe to open the back. If it’s showing any number at all, something’s currently loaded.

The camera prewinds film in order to determine how many shots are left regardless of what combination of formats is shot. Mix and matched frames will cause problems for scanners expecting regular spacing between exposures.

Winding the film this way does reverse scanning order, but as a (favorable) exchange, it also safeguards your exposed film against any kinds of accidental light leaks from prematurely opening the camera.

A standard 36exp roll of film yields around 20 shots, and a 24exp one produces about 12. I tend to bulk roll somewhere around 20 “regular” frames to get short, 10-shot rolls that are the perfect length for my usual outings.

Two CR2 batteries power the camera, and are installed via a screw-in covered slot set into the bottom of the camera. I use rechargeable batteries and find they last for a very long time. The camera wakes almost instantly from standby and powers on at about the same speed, and with little more than the meter, shutter, and winder to run, it’s rare to run down the batteries while in the field.

I have never experienced significant idle drain, so you’re safe to leave the batteries in the camera for long periods of time (sometimes months between power-ons in my case; I also haven’t recharged my current batteries in over a year, during which I’ve taken at least 349 images).

Stowage

When out and about, the entire system fits into my ONA Prince Street bag very comfortably, with any combination of camera and lens fitting into about half of the bag’s length and the unmounted lenses slotting between dividers.

For my typical loadout (the 90/4 and one other lens), the ONA bond Street works just as well.

In general, I keep my bag arranged such that the camera fits with the 90/4 mounted. Though the hoods add bulk, all three lenses have similar enough profiles to fit in the same spots when detached– but when mounted, it’s a different story.

Thoughts

The highest praise I can afford the Fujifilm TX-1 is that I cannot remember missing an opportunity through some fault of the camera. Everyone loses shots from time to time, but mine have been through operator error (lack of situational awareness, hesitance to commit, or simply forgetting which way the lenses turn).

In the field, the camera has always gotten out of my way and let me focus on taking pictures.

In fairness, the simpler a camera is, the less room there is for it to influence your results. The Fujifilm TX-1 has no autofocus system to fail, and the autoexposure system relies on a simple and predictable center-weighted meter. This is ultimately a light-tight box with a clock and some glass strapped to it, and most of the shooting process falls on the photographer.

You really get the sense that the entire system was designed to execute one specific function– and nothing more.

Personally, I prefer this no-frills approach. In the past, I’ve owned Nikon DSLRs with rock-solid fundamentals and all the bells and whistles– then had to give them up because they were simply unkind to my back. Almost every subsequent camera (particularly in the digital mirrorless world) has felt lacking in comparison– less accurate, less quick, and much more frustrating.

Having a once-in-a-lifetime shot get away because your equipment doesn’t keep up with your expectations is disheartening. I would far rather lose a photo because of my own failings; at least then I know that practice and forethought can help me improve.

Every so often, I wish that there were a longer lens than the 90/4– but rangefinders have never been exceptional at longer focal lengths due to their nature, and the Fujifilm TX-1 system offers exceptional coverage in a compact package that would be difficult to retain with longer or wider glass (or faster apertures, for that matter).

Speaking of the lenses, I have no issues with any of them apart from wishing they could just be a bit faster. As light wanes hour by hour (and through the course of the year), I find myself bargaining for every stop of shutter speed I can manage. In adverse conditions I often end up setting 1/60s and leaving my fate up to stand development and post work.

Given the capabilities of modern scanners and digital editing tools, even thin negatives (to say nothing of thinner portions of well-exposed negatives) are generally quite usable. For this reason, I have always refused to use the center ND filters on the 45/4 and 30/5.6. These lenses already guzzle light, and I both find their natural vignetting unobtrusive and easy to correct.

Note that the sample images in this article were edited to my taste– none of these are “straight out of camera” (or scanner, for that matter). If you are looking for test chart examples of what the lenses’ natural falloff looks like, I simply don’t have any to show– and you’ll have to bear in mind that I’ve added vignetting in many, if not most of these images.

I predominantly use the Fujifilm TX-1 in NYC (I have never been especially taken with, or good at landscape photography), and so my experiences with the system focus on handling and speed rather than absolute image quality. The lenses are optically superlative, but you are ultimately shooting on 135 film, with all the benefits and limitations that that entails.

On the balance, I think that’s a huge blessing. A huge variety of film stocks are made in the 135 format, and there are some great options for bulk rolling at home. My scanner (a Noritsu LS-600) can scan whole rolls easily and efficiently, and the files (8-bit, ~44MP JPEGs) are more than enough for my digital and print purposes.

I have long maintained that most of history’s iconic images are known for what’s in them, rather than for any level of technical quality. The obsession with squeezing every bit of “IQ” from gear is totally lost on me– so while this system is perfectly capable of excellence, the fact that it’s “good enough” for what I do is all I need.

Rationale

I wanted to take a moment to address one of the most common comments I see about the Fujifilm TX-1: “Why do it this way?”

It is a valid, fundamental question. There are a variety of ways to get to a panoramic image– the most obvious of which is to simply crop after the fact.

Even if you want to get to your frame in-camera, other models can achieve this with swing lenses (like the Noblex or Widelux) or by masking parts of the image circle (using variable film gates in the case of many point-and-shoots, or by mounting 135 carriers in medium format cameras).

For me, it’s a two part answer.

The case for seeing what you get

Getting as close as possible to your desired final result (in terms of perspective, crop, and distortion) in-camera matters a lot. You can work real magic in post, but the more you get right from the jump, the easier and more natural your workflow will be.

Being able to see what the camera sees takes a lot of the guesswork out of the process. You don’t have to worry about how moving objects may distort through a swinging lens, or try to imagine what your crop would look like through a viewfinder that knows nothing about your intent.

If this really didn’t matter, we would all be better served by simply taking ultra-high-resolution images through wide lenses of everything in front of us, then cropping to whatever we wanted later on (this is obviously a bit reductive since you’d still have to move around for perspective purposes and such, but you take my point).

But even when this kind of shooting does work, I think you lose a lot when you surrender the ability to make deliberate choices at the time of shooting. With intent comes focus, and with focus comes results.

Image quality after all

While absolute image quality is not a priority for me, I want enough to get the job done– and I want it without having to carry more than what’s strictly necessary. The Fujifilm TX-1 was specifically made to use as little glass, metal, and rubber as it can get away with– and that renders it irreplaceable to me.

You absolutely can use a compatible medium format camera with a 135 back (or fix 135 film to 120 spools), but now you’re carrying a lot of camera and lens that isn’t doing anything for you. Bulk is a barrier to use, and any time your camera gets left at home is time that it won’t be taking pictures at all.

Conclusion

The Fujifilm TX-1 is ultimately an eccentric, niche camera that is even more limited by its high price and aging internals. On top of that, there are no easy ways to get a similar experience to test things out for yourself– the system is just too unique for other options to get particularly close.

But to my mind, the ability to see and shoot in this beautiful format with a camera that’s manageable in the hand and in a bag without conceding quality is one of a kind.

It’s absolutely not a camera for everyone, and many will never even get a chance to try it.

But if you do, you might find yourself feeling the same way I do– that at the end of the day, this is the camera that clicks.

—-

Postscript

A companion piece on the Minolta P’s, a crop-frame panoramic point and shoot made by Minolta, is complete as of the time of writing. An additional head-to-head comparison article is in the works as of the time of writing.

Share this post:

Comments

Thomas Wolstenholme on Fujifilm TX-1 – Nine Years in – Both Eyes Open

Comment posted: 05/01/2026

I like the work you've done with the Fuji, inlcuding the landscapes which you say you're not good at making. They are all very good work and I thank you for them also.

Comment posted: 05/01/2026

John Hillyer on Fujifilm TX-1 – Nine Years in – Both Eyes Open

Comment posted: 05/01/2026

Comment posted: 05/01/2026

Comment posted: 05/01/2026

Christian on Fujifilm TX-1 – Nine Years in – Both Eyes Open

Comment posted: 05/01/2026

I had a lot of fun doing really big panoramas (24x90) with it, but a few years in, I only shot about 3-4 rolls with it...

The lenses of the 690 series of Fuji Rangefinders also are stellar... at a great price point...

maybe I will try some more, as I now also cheaply aquired a russian Swing-lens-Cam (Horizon 202) to try some swing-panoramas...

Will try to write some articels about them soon, but thanks again for this great insight in using a TX1!

Comment posted: 05/01/2026

Fidel on Fujifilm TX-1 – Nine Years in – Both Eyes Open

Comment posted: 05/01/2026

I do miss my xpan, at the time I didn't get along with it, now I can see myself using it a lot. Bought for pennies and sold for pennies, unfortunately that's not the case anymore

Comment posted: 05/01/2026

Jonathan Murray on Fujifilm TX-1 – Nine Years in – Both Eyes Open

Comment posted: 05/01/2026

Comment posted: 05/01/2026

Kodachromeguy on Fujifilm TX-1 – Nine Years in – Both Eyes Open

Comment posted: 06/01/2026

https://worldofdecay.blogspot.com/2022/11/the-mississippi-delta-38b-hwy-49w-and.html

Comment posted: 06/01/2026

Alexander Seidler on Fujifilm TX-1 – Nine Years in – Both Eyes Open

Comment posted: 06/01/2026

Alexander K on Fujifilm TX-1 – Nine Years in – Both Eyes Open

Comment posted: 06/01/2026

Comment posted: 06/01/2026

Michael on Fujifilm TX-1 – Nine Years in – Both Eyes Open

Comment posted: 07/01/2026

Comment posted: 07/01/2026

Alastair Bell on Fujifilm TX-1 – Nine Years in – Both Eyes Open

Comment posted: 07/01/2026

Comment posted: 07/01/2026

Steve Abbott on Fujifilm TX-1 – Nine Years in – Both Eyes Open

Comment posted: 11/01/2026

I've recently taken a different path into pano picture taking, and whilst you're confirmed in your setup, other readers might be interested in my alternative route, which can be found here:-

https://www.35mmc.com/15/12/2025/chroma-camera-cubepan-a-review-and-my-journey-into-panoramic-photography/

Thanks again!

Comment posted: 11/01/2026