Antoine Bourdelle isn’t a household name in the U.S. But he’s nearly legendary in France. His life stood squarely at the crossroads of European art’s transition from Beaux-Arts Greco-Roman mythologcal themes to modern abstraction. Specializing in sculpture, Bourdelle studied under Auguste Rodin, and in turn, taught Giacometti, Matisse and at least 45 other international artists.

Along the way, he became instrumental in a movement that is still popular: “Arts Décoratifs” (later shortened to “Art Deco”). It originated in response to highly ornate earlier styles. Deco designers favored sleek, simple geometries, bold colors and high-end materials. And in an effort to elevate their work to the level of “high art,” they staged a 1925 Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes in Paris.

It worked. Art Deco spread from France to Europe and the U.S. And it soon influenced almost every aspect of global art, architecture and industrial design.

The Bourdelle Museum

During a 2010 trip, Kate and I made a point of visiting the Musée Bourdelle in the 15th arrondissement on the Seine’s left bank. Between 1885 and 1929, it had been Bourdelle’s studio and school. But he began thinking about turning it into a museum as early as 1922. It eventually opened to the public in 1949, and was expanded in 1961 and again in 1992.

Its 2,000 statues and plaster casts– plus paintings, pastels, frescos, sketches, and Bourdelle’s own personal art collection– are a treat for lovers of early Deco. But I wanted to photograph the statues and wall panels in and around the museum’s central outdoor courtyard. With statuary scattered among natural plantings, it was an ideal subject for my IR-converted Nikon CoolPix 990.

And though I love Deco, it has some unique quirks that are evident in my photos.

Broken Necks and Wrists

I’d long wondered why Bourdelle and his contemporaries produced statuary with apparent broken necks and sprained wrists. Like these:

I thought they were inspired by the angular Egyptian art that had exploded in popularity following Howard Carter’s 1922 discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb. The early Saturday Night Live did a hysterical parody of this angularity in Steve Martin’s unforgettable “King Tut” performance. If you forgot it (but how could anyone), here it is— perhaps the funniest musical dance number ever to hit the airwaves!

But in fact, while Art Deco did borrow heavily from Egyptalia, its chief design goals were sleek lines, simple shapes, powerful dynamism and “modernity.” This extended to anatomical depictions. Like the swept-back tailfins of 1950’s autos, Bourdelle’s anatomic distortions of necks, arms and hands sought to create a never-before-seen illusion of dynamic motion and speed.

Maybe so. But a term that’s been applied to Art Nouveau’s more graceful, sinuous, flowing designs– “Whiplash Lines”— seems more appropriately applied to these Deco distortions!

Into the Garden

So much for theory. Take a virtual stroll now through Bourdelle’s sculpture garden. The following photos are arranged in the order we encountered the pieces during our walk. And I’ve done my best to provide translated names in the captions. (The featured image at the top of this article is from “Meditation of Apollo and the Muses.”)

Why so Many Apollos and Muses?

On a lark, I asked Google’s AI crawler why Apollo and Muses were featured so often. It returned an essay (with citations) that might well receive A+ on a student assignment. Here’s a short excerpt:

“Emile-Antoine Bourdelle frequently featured Apollo and the Muses in his sculptures due to his deep admiration for ancient Greek art and its connection to his artistic philosophy. Here are the key reasons why Bourdelle was drawn to these themes:

- PASSION FOR ANTIQUITY: Bourdelle had a strong passion for ancient Greek art, especially the Archaic period. He found inspiration in its clean lines, uncluttered forms, and strength, and sought to incorporate these elements into his own work, deviating from the aesthetic of his mentor, Auguste Rodin.

- APOLLO AND THE MUSES AS A REPRESENTATION OF THE ARTS: Apollo is the Olympian god of music, arts, and prophecy, and is often depicted as the leader of the Muses, who embody artistic inspiration and creativity. By featuring them together, Bourdelle emphasizes the collective nature of the arts and the divine inspiration behind them.

- INFLUENCE OF ISADORA DUNCAN: Bourdelle was inspired by the dancer Isadora Duncan and her focus on gesture, rhythm, and simplified forms. He applied these principles to his sculptures of the Muses for the theatre, giving them a more graphic and unified appearance.”

Generated in seconds, the entire document might have required hours of old-fashioned online research. No wonder educators worry about incorporating AI in their curricula. It’s pretty obvious, though, that many students wouldn’t write with such polish on their own!

A French Tribute

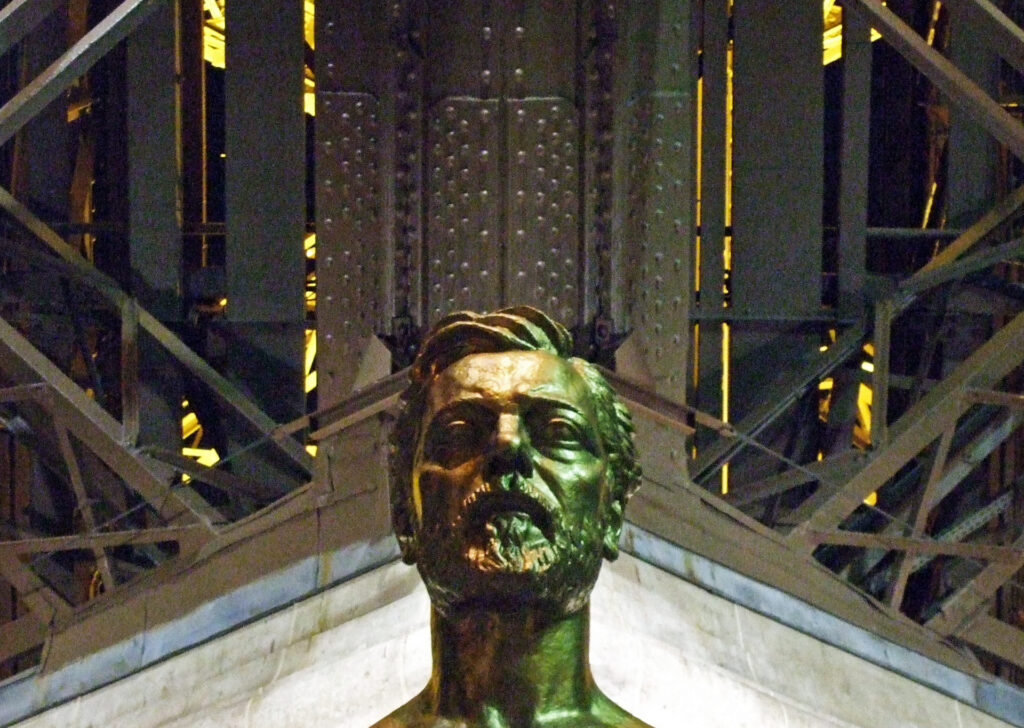

The Eiffel Tower was completed on May 15, 1889. But it wouldn’t be until May 2, 1929 that a gilt bronze bust honoring Gustave Eiffel was unveiled at the foot of the tower’s north pillar:

And the esteem that France holds for Bourdelle is seen in their choosing him to forge the bust.

–Dave Powell is a Westford, Mass., writer and avid amateur photographer.

Share this post:

Comments

Geoff Chaplin on In a Paris Sculpture Garden (with an IR-converted Nikon CoolPix 990)

Comment posted: 27/07/2025

Comment posted: 27/07/2025

Charles Higham on In a Paris Sculpture Garden (with an IR-converted Nikon CoolPix 990)

Comment posted: 27/07/2025

Comment posted: 27/07/2025

Tonn on In a Paris Sculpture Garden (with an IR-converted Nikon CoolPix 990)

Comment posted: 27/07/2025

But as always in life, something happens and you never quite get there (Like the lady in the book: 84 Charing Cross Road).

I don’t have a IR camera, but I do like your pictures, wild and strange.

Comment posted: 27/07/2025

Louis A. Sousa on In a Paris Sculpture Garden (with an IR-converted Nikon CoolPix 990)

Comment posted: 27/07/2025

Comment posted: 27/07/2025

Gordon Ownby on In a Paris Sculpture Garden (with an IR-converted Nikon CoolPix 990)

Comment posted: 27/07/2025

Comment posted: 27/07/2025

Gary Smith on In a Paris Sculpture Garden (with an IR-converted Nikon CoolPix 990)

Comment posted: 27/07/2025

Is your camera converted to full spectrum?

Thanks for more IR. I have a gx85 that I had Kolari convert to 590nm and I wonder if I should have gone full spectrum for flexibility.

Dave Powell on In a Paris Sculpture Garden (with an IR-converted Nikon CoolPix 990)

Comment posted: 27/07/2025

But returning to the Nikon 990. The "native" IR colors from its CCD sensor are unique. Most other cameras I've tried output files that are too pink or purple... or completely monochrome (depending on the filter strength). But I've always left the 990's colors untouched 'cause they're so beautiful. Different cameras with "full-spectrum" conversions will behave differently. There's no predicting... only experimenting!

Comment posted: 27/07/2025

Comment posted: 27/07/2025

Marco Andrés on In a Paris Sculpture Garden (with an IR-converted Nikon CoolPix 990)

Comment posted: 28/07/2025

Infrared certainly brings out different aspects of Antoine Bourdelle’s work. Appreciate the introduction to his work. The pinkish cast seems like a take on a platinum print in the images devoid of ghostly green foliage.

Many of the images are reminiscent of the bas reliefs on the exterior of Rockefeller Center in. New York City, designed by Lee Lawrie who also designed the free-standing Atlas sculpture. Another American sculptor, Rene Paul Chambelian, also designed some of the ornamentation in the centre in “The New French Style”. The ornamentation is in the Art Deco style that formed a link between Beaux Arts sculpture and Modern sculpture,

Comment posted: 28/07/2025

Ibraar Hussain on In a Paris Sculpture Garden (with an IR-converted Nikon CoolPix 990)

Comment posted: 30/07/2025

You brought the sculptures to life with the IR and the hues - fantastic stuff I enjoyed again and again.

As for Apollo there may be esoteric and or occult reasons why he and his muses feature

Comment posted: 30/07/2025