Most people coming into film photography start with the camera and then try to figure out how to scan the results. I went the other way.

I shot film for 30 years, finally switching to digital around 2000. A few years ago, I decided to digitize all the work I did — somewhere upward of 10,000 images — during my peak film period (1966-1983). Since this included both 35mm and 120 film, I acquired a suitably expensive Nikon LS-9000 batch scanner (long out of production) to do the work.

I’d been happily using the scanner for a while to digitize my old 35mm and 6×6 negatives when I realized that it could actually scan 6×9. So I couldn’t resist checking this out by buying a Horseman 980, which is a lot like a less expensive Linhof Technika and a little bit like a smaller version of a Crown Graphic. Three years later, it’s a complete kit, with four lenses and an inverting viewfinder. I love using this camera.

In October, I took advantage of idle time while visiting my daughter to spend several days on a project I began last year at this time, which is to document all the grain elevators in the country surrounding the town where she lives in Illinois. The photos from this year’s batch that I’m presenting here show the quality you can expect from such a camera as the Horseman and illustrate one of its most important features, the rising front.

Here are two iPhone photos of the setup, on location, used to take these pictures. The lens is elevated slightly in relation to the back of the camera — this is the rising front. The finder attached to the back re-inverts the inverted image on the ground glass so that I can compose the picture without trying to imagine it upside down. The image is still reversed left to right, but that’s a lot easier to deal with. When it’s time to take the picture, the viewfinder is replaced with a 6×9 film back; I have several of these, which allows me to suit the film type to the subject. All of the photos you see here, however, were taken on the same film, Ilford FP4+, developed in the same developer, D-23, which I mix up myself from scratch. With the finder taken off, everything else folds up into the little box in the middle.

The first photo in this set (see top of article) was taken at the Premier Cooperative grain elevators in Tolono, Illinois. No lens movements were used, though a red filter was attached to the 150mm f/5.6 Super Horseman lens to darken the sky. This picture illustrates the technical quality of which this old camera is capable and also shows off the characteristics of the tessar lens design. The 150mm Horseman lens has only four elements rather than the six elements of my other normal lenses (65mm and 100mm), but it’s the sharpest of the lot, including three other six-element Horseman lenses that I no longer own. (Even Horseman said that the 150mm was their sharpest lens.) With all tessars, the secret for getting results like this is to stop the lens down to f/16-f/22 (or f/11-f/16 on 35mm cameras). Here the aperture was actually set to f/32.

The reason that this lens at its best is (slightly) sharper than the other two more sophisticated lenses is that at 150mm, coverage of the 6×9 negative is easy, and no special design is needed to increase the angle of coverage in order to allow lens movements. The 65mm and 100mm lenses, however, have to cover a much wider angle while allowing for some movement while still producing an image completely free from distortion. These additional requirements can only be met by trading off a tiny amount of resolution for increased coverage and incurring a tiny reduction in contrast due to the greater number of glass-air surfaces.

This is not to say that the 65mm and 100mm lenses aren’t capable of impressive performance, however. The next picture was taken at “The Andersons” (Champaign, Illinois) with the 100mm f/5.6 Rodenstock Apo Sironar-N, again with a red filter.

For the next photo, the 65mm f/7 Super Horseman lens was used to take a picture of the Premier Cooperative of Galesville, Illinois, once more with the red filter. If this picture had been taken with any of the vast majority of film cameras, the camera would have had to be tilted upward to get that much sky in the frame, and the grain elevators would have appeared to be falling backwards. But with the Horseman, the camera can be kept level and the image framed properly by raising the position of the lens with respect to the film plane. In the viewfinder, moving the lens upward moves the image downward, just as tilting the camera would have done, but keeping the camera level keeps the verticals truly vertical.

The 65mm lens can also be used to create panoramas simply by cropping the top and bottom of the image, as in this photo of the Frito-Lay Midwest Corn Handling Facility in Sidney, Illinois. (A deep yellow filter was used for this one.) Since it can cover a 6×9 area with room for lens movements, the 65mm can actually be used with a 6×12 film back to make the Horseman into a genuine panoramic camera, or at least a banquet camera. If these backs didn’t cost a small fortune, I would certainly use one!

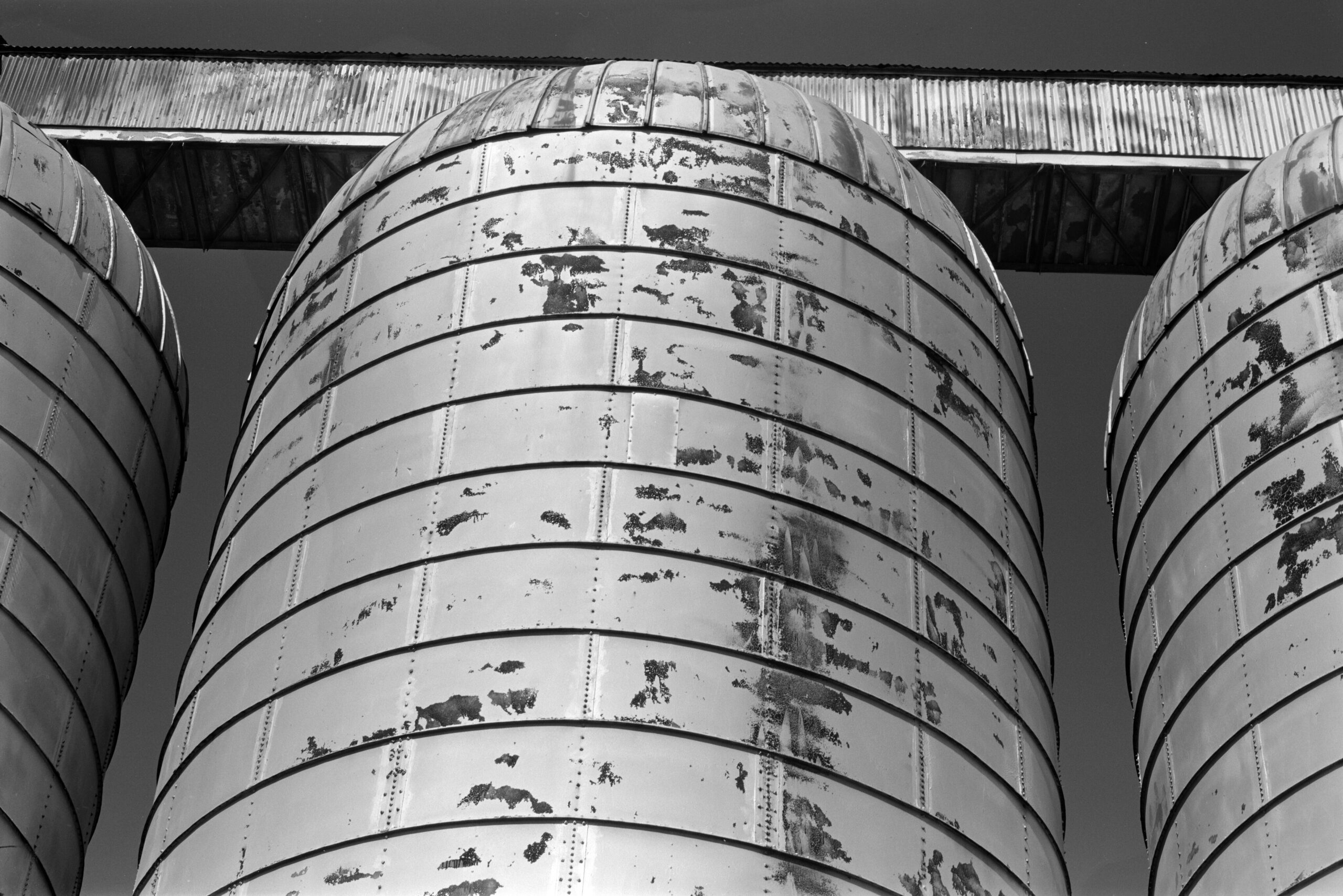

On the last day of shooting, I chanced upon an abandoned set of grain elevators that allowed me to get close for the first time. The first photo is a conventional view looking upward with the 150mm.

The photo that ends this set, taken with the 150mm at the same abandoned set of grain elevators, is less theatrical, but it illustrates why I really like working with this camera.

With most cameras, positioning the frame as you see it here would require tilting the camera up a little, which the eye would interpret as “looking upward.” In this case, the effect would have been muted by the omission of the topmost sections of these structures, but there would still be the sense, however subliminal, that you were looking up, which is what the camera was actually doing. And this would lead to the sense that the top parts were receding from you, which of course they were. The psychological effect of this would be to de-emphasize the top part of the picture and reduce its impact. It would be less visually present to you.

In this case, however, the camera is level, and the rising front is used to obtain the same framing. Because the camera is level (this is the important thing), the eye “knows” that you are on the same level as the door and are looking right at it.

The door is low down in the frame, but it is psychologically at the center of the image, just as it literally was optically when I took the picture. The eye knows that it is looking directly at this structure rather than looking up at it. The net effect is to give the upper part of the structure a solidity and presence that it would not have if it were sensed as receding from you. If this image is viewed on a large screen, the elevators seem almost to loom over the viewer.

Share this post:

Comments

Giuseppe on Horseman 980 – A Seasonal Essay

Comment posted: 04/12/2025

Giuseppe

Comment posted: 04/12/2025

Thomas Wolstenholme on Horseman 980 – A Seasonal Essay

Comment posted: 04/12/2025

Comment posted: 04/12/2025

Art Meripol on Horseman 980 – A Seasonal Essay

Comment posted: 04/12/2025

Comment posted: 04/12/2025

Comment posted: 04/12/2025

Simon Foale on Horseman 980 – A Seasonal Essay

Comment posted: 04/12/2025

Comment posted: 04/12/2025

Comment posted: 04/12/2025

Comment posted: 04/12/2025

Kodachromeguy on Horseman 980 – A Seasonal Essay

Comment posted: 05/12/2025

Comment posted: 05/12/2025

David Pauley on Horseman 980 – A Seasonal Essay

Comment posted: 06/12/2025

Comment posted: 06/12/2025

Jeffery Luhn on Horseman 980 – A Seasonal Essay

Comment posted: 12/12/2025

Great images. Yes, very much in the style of Margaret. Great tones! I recently acquired a Horseman 980 with a 90mm lens. After a minor adjustment to the rangefinder, it works perfectly. Not the first choice of a camera I'd handhold. It's a heavy beast! But on a monopod, it can be pretty fast. I have a couple of Zeiss Ikon 6x9 folders and I believe the Horseman and coated lens is actually sharper. Certainly better contrast because of the coated lens. Quite a nice looking camera! Always get comments on it.

Jon Bosak on Horseman 980 – A Seasonal Essay

Comment posted: 12/12/2025