By way of introduction, fellow contributor David Pauley and I are doing a variation on the “Five Frames” post where I will be leading a conversation about five frames of David’s, and he will look at five frames of mine in a companion post. This idea came out of how much we’ve enjoyed the dialogue with the 35mmc community in the feedback section of the blog and is a bit of an experiment to try to bring that spirit and engagement between photographers into the text of the post itself.

I want to thank you, David, for your willingness to give this a shot, and say how much I’ve admired both your photography and your writing on 35mmc! Caveat: my responses to your photos say far more about me as a viewer than they do about either you as a photographer or the people and places you are shooting. My reactions to this photo set in particular are very personal to me, so I want everyone to read them in that context. And if I’ve missed badly on interpreting anything or imposed my story onto someone else’s, hopefully you’ll set us all straight!

So without further ado, here we go….

SCOTT: There’s something a bit ‘hard scrabble’/Rust Belt about these photos that makes me immediately think of my youth in Pittsburgh, where I know we both grew up but also both left behind to try to make a life in New York, where we now live in adjacent neighborhoods of Brooklyn. Although there are a few clues that these were shot in the 21st Century, they bring me back to the way things felt for me in the 1970s when America was turning 200 years old, and I was trying to figure out who I was and where my future would lead.

DAVID: Thank you, Scott! I’m thrilled to hear that these images from my hometown of Beaver, Pennsylvania prompted memories from the 1970s for you, which I guess shouldn’t seem so remarkable given that we’re around the same age and grew up about 30 miles from each other… but still does. The photos here were made between 2019 and 2025 within about a three-mile radius of the house where I was raised, in a town where my family has lived since the 19th century.

SCOTT: Interesting that these were shot over a six-year period. It would have been unsurprising to me if you had told me that they were all from the same roll. It speaks to a certain consistency of style—a voice as a photographer—that is something I don’t think I’ve really settled into yet.

DAVID: I think this settled style is probably most apparent when I’m shooting photos back in Pennsylvania.

SCOTT: I love the energy of this shot that feels like a hybrid of a candid captured moment and a posed double portrait. The composition is interesting, with the main subjects—the boys and the dog—in the bottom half of the square frame, but a lot of important information in the top half of the frame: an older middle/working-class house with a collapsible camping chair on the front porch, what looks like a US Marine flag, and a holiday wreath on the door in spite of the fact that it’s T-shirt weather.

I love that they have one Razor Scooter between the two of them, and the action is contained in the small yard enclosed with a sidewalk that feels like it’s very familiar playing ground for those boys. It’s the kind of sidewalk where I would have tried to set a newspaper comic strip on fire with the magnifying glass from a Swiss Army knife. The lunging dog energizes the frame, while the kids embody late-stage childhood/pre-adolescence—a time in my life where you could be very bored. When I was around that age there was a neighborhood boy, John F., who used to come over to my house every day one summer and we’d spend hours saying, “What do you want to do?” “I don’t know, what do you want to do?” Eventually we’d get bored of even that and come up with something to do that was repeating something we’d done just about every day before—whether it was riding our bikes, poking around the woods behind my house, or going to someone else’s house and asking them what they wanted to do.

DAVID: How funny, Scott! I had those same repetitive conversations with my friends at that age. Playdates were definitely not a thing back in the seventies…

SCOTT: The terminology has certainly changed. I think John F. might have punched me if I asked him if he wanted to go on a “playdate”…

DAVID: The thing I like best about this photo are the open and happy expressions on the faces of these two boys (they are brothers), their sense of being sovereigns in their own particular realms—their front yard, their porch—and whatever other haunts they may soon be heading off to after the shutter clicks. (In addition to the scooter, there’s a bike whose front wheel just barely noses into the lower right corner of the frame.)

SCOTT: As I am inclined to impose narrative, I saw that bicycle wheel but mentally framed it out. In my imaginary version, they have to make do with one Razor Scooter, leading to intermittent rivalries and conflict with periods of cooperation and sharing—like just about every Saturday morning with my brother and me during that phase of our lives.

DAVID: As the youngest of five brothers, I’m definitely no stranger to that particular narrative!

As it happens, these particular kids were total strangers to me. They noticed and were fascinated by my 1950s Rolleiflex as I headed “up street” from my mother’s apartment in search of coffee in 2021. Their mom was unloading groceries just outside the frame and readily agreed to a photo. The dog was also in the car and exploded onto the scene just after I set the shot up. His euphoria is magic—the random element that spiked the kids’ joy and elevates the photo from a potentially stilted snapshot to something a bit more lively. Even at 1/125th of a second, the shutter can’t keep up with his tail, though it does catch a string of saliva (at first I thought it was a scratch on the negative) as it corkscrews down from his face in mid-lunge.

SCOTT: I recently had a similar interaction with a boy about that age in the corridor of our building in Brooklyn. No, not a string of saliva corkscrewing down his face! Our neighbor’s son was transfixed by the Hasselblad and fascinated by everything about it—the size, the shape, and even the odd-sounding name, which he repeated quietly to himself a couple of times.

DAVID: Yes, Scott — these old film cameras are unbelievable conversation-starters!

At the risk of sounding like a psychoanalyst, I think the impulse to take pictures such as these when I return to my hometown has to do with some sort of grief about that place that will probably always have its claws in me.

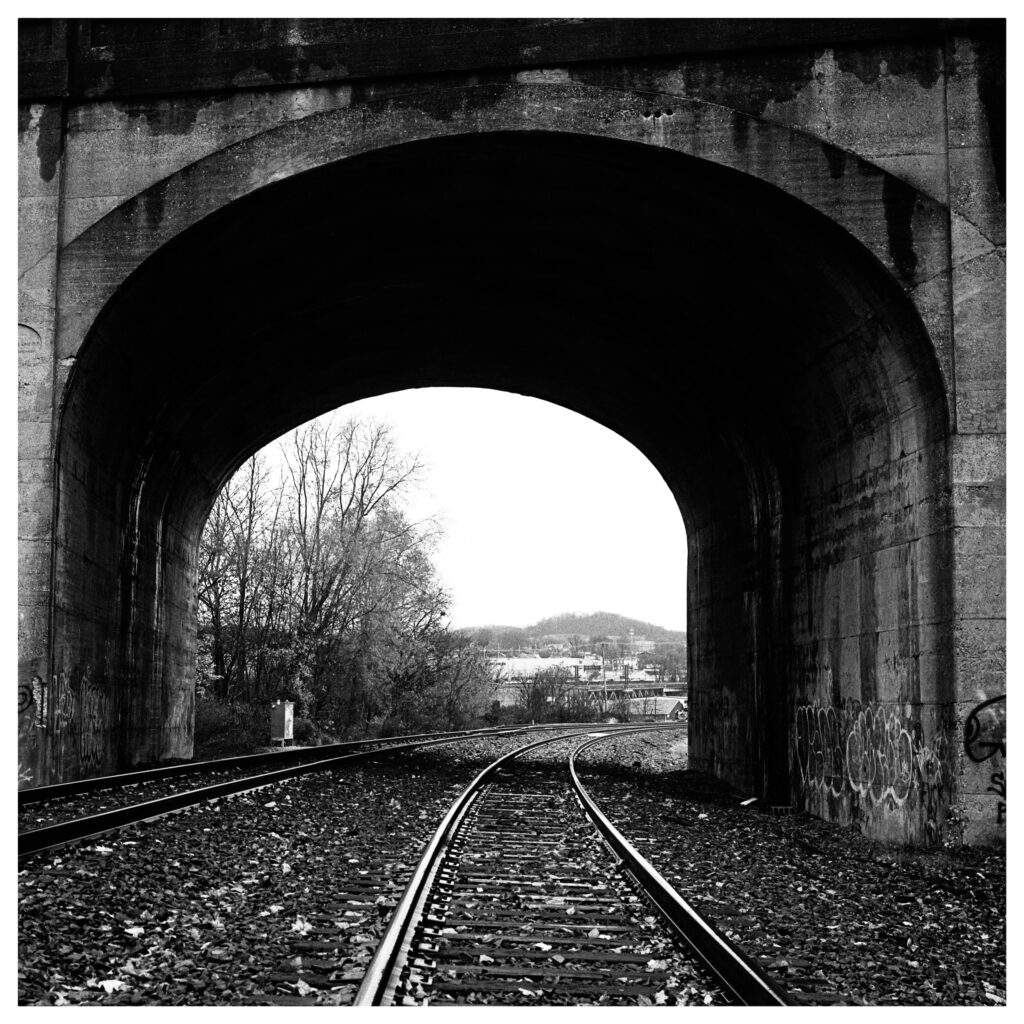

SCOTT: This railroad tunnel underpass is the kind of place John F. and I would have ended up poking around on our bikes. Maybe when we were younger we’d grab some broken sticks and pretend they were rifles and we were WWII soldiers on patrol. Or we might put pennies on the track so the train would flatten them. Maybe when we were a little older we’d throw glass bottles against the concrete wall or set off firecrackers or cherry bombs to see how much they echoed in the tunnel. Maybe when a little older than that, this might be a place to get high or sneak off with someone for some illicit pleasure…

But by the time I was that age, I had kind of opted out of my lowkey juvenile-delinquent-in-training years and was doing school plays — there is no place like the theater department for nerdy misfit dreamers — and working on getting out by doing my college applications in ballpoint pen at our kitchen table. Not sure about John…

DAVID: Once again, there are some uncanny parallels in our experience, Scott! As a kid I kept a flattened nickel—big as a silver dollar, split cleanly down the middle by a train—on my desk. My childhood friend Mike F. and I set it on the tracks and watched the locomotives roll over it from a safe vantage point in the brush, a small act of delinquency that my parents would have gone berserk over had they known about it.

SCOTT: I really like the composition and the geometry of this shot, with the curves of the tunnel and the curving tracks receding into the distance. I also love all of the textures and tonality within the monochrome frame — the absorbing blackness of the deep shadows on the roof of the tunnel against the whiteness of the sky, hints of the graffiti on the tunnel that is a different style than we had in my younger years but not unfamiliar, all framed by the dense & gritty yet elegant curves of poured concrete. I like that you cut off whatever is above the tunnel, which encloses and constricts the image. Perhaps that’s why it evokes a time when I might have been potentially facing choices that could lead to a more or less constricted future…

DAVID: My hometown is crossed by two sets of railroad tracks, a north-south route and an east-west route. This photo is taken at the place where the two train lines cross: the former Pittsburgh and Lake Erie line is on a trestle above the tunnel, the former Penn Central line—the tracks shown in this frame (I have no idea which conglomerate owns them now)—stretch out eastward to the next town and eventually the East Coast. In practical terms, the tunnel marks the terminus of my hometown, the outer geographic boundary also of my early childhood.

While railroad tracks were a scene of adventure for me and my young friends, they also have darker associations. A teenage classmate of one of my brothers was killed by a train a mile or so from where this photo was taken. My parents and most of the other adults around town blamed drugs, a scourge that by the mid-seventies was already wreaking havoc with many local teenagers (addiction, alas, is also woven into my family history). From my ten-year-old’s perspective, this incident only seemed to hammer home the grownups’ warnings.

I only learned decades later that the boy in this tragic accident was very possibly gay, and that his death may have in fact been suicide. While I had a pretty strong sense of my own homosexuality by the age of ten or twelve, I was savvy enough by that point to know that I needed to conceal it, and that there were few, if any, congenial spaces for “people like me” in the world where I was growing up. (I’m sure that may be different now, but in the 70s and 80s it was undeniable). In that sense, those curving tracks—heading east through the dark tunnel to places like New York City, and salvation—are also symbols of hope, though obviously that’s a personal overlay not legible in the photo.

SCOTT: Wow… Growing up gay in that era in a town like Pittsburgh had to be tough. A number of my closest friends in high school were gay but didn’t start to come out until they were safely away in a more accepting peer situation at college. I feel badly that I wasn’t a better friend to them at that age and regret some of the crude humor and my own discomfort and insecurity that gave rise to it.

DAVID: Teenage boys are among the most insecure creatures on the planet!

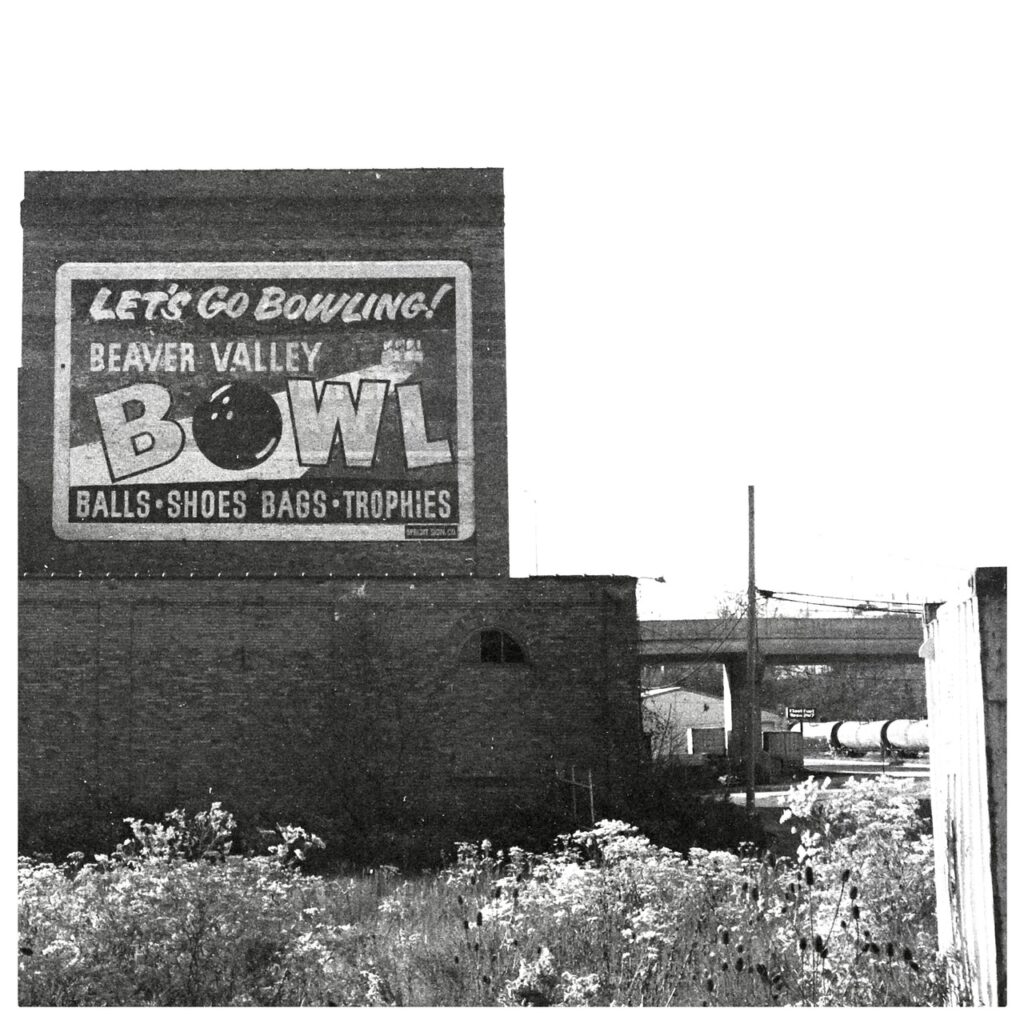

SCOTT: I’ve always liked finding the old painted advertisements on the sides of buildings as a bit of a time capsule to an earlier era, and a lost art. In the 1990s I did a couple of films that were set in small towns that had those kinds of wall paintings, and we liked to photograph them for montages that conveyed the atmosphere of decay/stagnation, like time has passed that place by. I can’t remember how many made it into the finished films, but we liked shooting them.

Bowling itself feels a bit like a lost art, apart from kids’ birthday parties or the odd hipster place in Williamsburg. I remember going to all-night bowling sessions at the lanes where I grew up during those bored and boring teenage years, and then on holidays from college because they were known to serve beer without checking ID…

DAVID: Unlike the railroad tracks, which have complex connotations for me, this photo memorializes the place where I — and my parents before me — learned to bowl. (Badly in my case). Visually I have always been taken with this building, the structure where the Beaver Valley Bowl operated from the 1930s until the 2010s. Its location — in a tumbledown industrial wasteland alongside the Ohio River abutting the town of Rochester — seemed kind of unexpected to me at the time, but also as I grew older, increasingly cool.

SCOTT: Interesting to see the word ‘cool’ in a sentence about bowling, but I do remember a brief minute in 1980 or ’81 when bowling shoes had a little bit of punk/new wave scuzzy cachet, at least among the suburban wannabe’s I was running around with… By the way, this photo was the ‘tell’ that at least this one was shot in the Greater Pittsburgh area — I remember excursions into the Beaver Valley when I was at the ‘pennies on railroad tracks’ age.

I think the image is very interesting, with the subject more or less in the left half of the frame, but like the shot of the two kids, with important information in the deeper background — some old tanker cars, a squat bridge that looks like it’s not going anywhere interesting, and maybe a dumpster on the right foreground edge. While this shot has some of the same unfussy industrial textures as the railroad tunnel, the geometry and composition is much more straight, flat and direct. There is little sense of depth, movement or promise of a world beyond — the photo shows what it shows and that’s it. While it refers to the happy communal activity of bowling from a time in the past, there is a strong sense of neglect and decay, with weeds choking the foreground and trees growing around the building.

DAVID: Yes! Decay is the perfect word. In those formative years, the bowling years, there was also a kind of unquestioned conviction among us that our hometown was a fantastic place to live, and that, like our parents, we would find some way of arranging to remain there forever. At that stage of childhood, this vision of the future was stronger than a belief — more like a religious principle.

That life didn’t play out that way for me or any of my four older bothers — for myriad reasons I was totally unprepared for — is the scab that I pick when I am back there making photos.

SCOTT: The geometry of this frame is very interesting, with so many strong shapes in a somewhat disorganized array — nothing lines up neatly or seems to relate to anything else in a coherent way. The house feels oddly placed in relation to both the garage outbuilding and the bridge, which feels uncomfortably close, as if everything was built in an era before there was much zoning. The car looks like it might be on the lawn, and the haphazardly placed dumpster and trash barrel dominate the foreground on a street that seems to be dead-ending at the waterfront or following a bend in the river, along with power lines that look almost like they are plummeting into the ground only to take an oblique turn to the left of frame. There is a drab utilitarian quality to the situation — nothing is there for presentation except a small U.S. flag. The complex geometry of the bridge dominates the frame, but it doesn’t give a sense of mobility — the visual subtext is cage-like, closing off rather than opening up a way to someplace else.

I feel like I’m probably overreacting to what is quite likely the home of dignified, hardworking Americans, and don’t want to come off as some kind of “Coastal Elite.” Part of what I’m feeling is how much this is part of the fabric of who I am. My house was the one on my street that was a disorganized mess. We were the family that would probably have a Christmas wreath still up in May or June; we had an actual bulldozer in our yard for about ten years because my dad couldn’t be bothered to get rid of it. It was a great place to play like you were part of a WWII tank crew, but I think the neighbors who kept their nice suburban homes much tidier probably hated us…

DAVID: More than the other frames here, I would like to believe that this photo — and perhaps the next one also — shows the influence of one of my photographic heroes, Lee Friedlander. I became aware of his work while studying abroad in France in 1986–1987. In an art bookstore in Toulouse, I came across his 1982 work, Factory Valleys, the catalogue of an exhibition commissioned by the Akron Museum of Art. The museum’s curators charged Lee with documenting the life and landscape of the Ohio River Valley — Pennsylvania and Ohio — not knowing at the time that the steel belt he was photographing, and their own community, would soon be eviscerated by de-industrialization. Looking through Lee’s photos from half a world away, I felt a sharp homesickness that was absent in my otherwise very happy year abroad. I wasn’t identifying so much with a specific location, but with the deeper vibe. On some profound level Friedlander’s understated photos seemed to capture the soul of the place where I grew up — the somber dignity of the people and the gray-scale landscape that I still feel connected to, even after almost 40 years away.

SCOTT: I don’t know Lee Friedlander’s work, but I’m excited to have a look.

DAVID: Factory Valleys is definitely worth a look. Here’s a link to a video from the Museum of Modern Art where photographer LaToya Ruby Frazier reflects on the resonance of Friedlander’s book for her own work. https://www.moma.org/magazine/articles/1102

This particular photo shows a house on the opposite bank of the Ohio River from Beaver, in the working-class town of Monaca. In my hometown, you see the massive iron bridge from a distance from a park overlooking the river, but as you noted, Scott, here the houses are pressed up close. I was taken with the layers in this scene. Impressive in other photographs, the iron bridge here seems to want to elbow away the tidy clapboard house, its own boundaries further encroached upon, as you mention, by the dumpsters and a car plopped haphazardly in the foreground. If the scene admittedly does not conform to a curated definition of beauty, for me its tensions give it an authenticity as a document of that place and moment, one I often aspire to as a photographer, but seldom reach.

SCOTT: For me, at least, your reach is pretty good. These photos also make me think of W. Eugene Smith’s brilliant photos of Pittsburgh from the 1950s. Do you know them?

DAVID: I’ve heard of him but have never seen his work. I can’t wait to have a look!

SCOTT: Apparently Smith was commissioned to shoot 100 photos over the course of three weeks for a coffee table book Stefan Lorant was writing as a feel-good paean to Pittsburgh. Smith, who was a passionate artist, kind of went off the deep end and spent a full year in Pittsburgh and shot over 17,000 photos, the biggest photo essay of his career. I think Smith and Lorant clashed on tone (and budget) and only 64 of Smith’s photos made it into Pittsburgh, The Story of an American City. We had a copy of Lorant’s book in our house when I was growing up; I think just about everyone I knew did. As I recall, I found it a bit boring when I was the age of the kids in your first photo. Many years later Dream Street was published, which gives a much better sense of Smith’s Pittsburgh project.

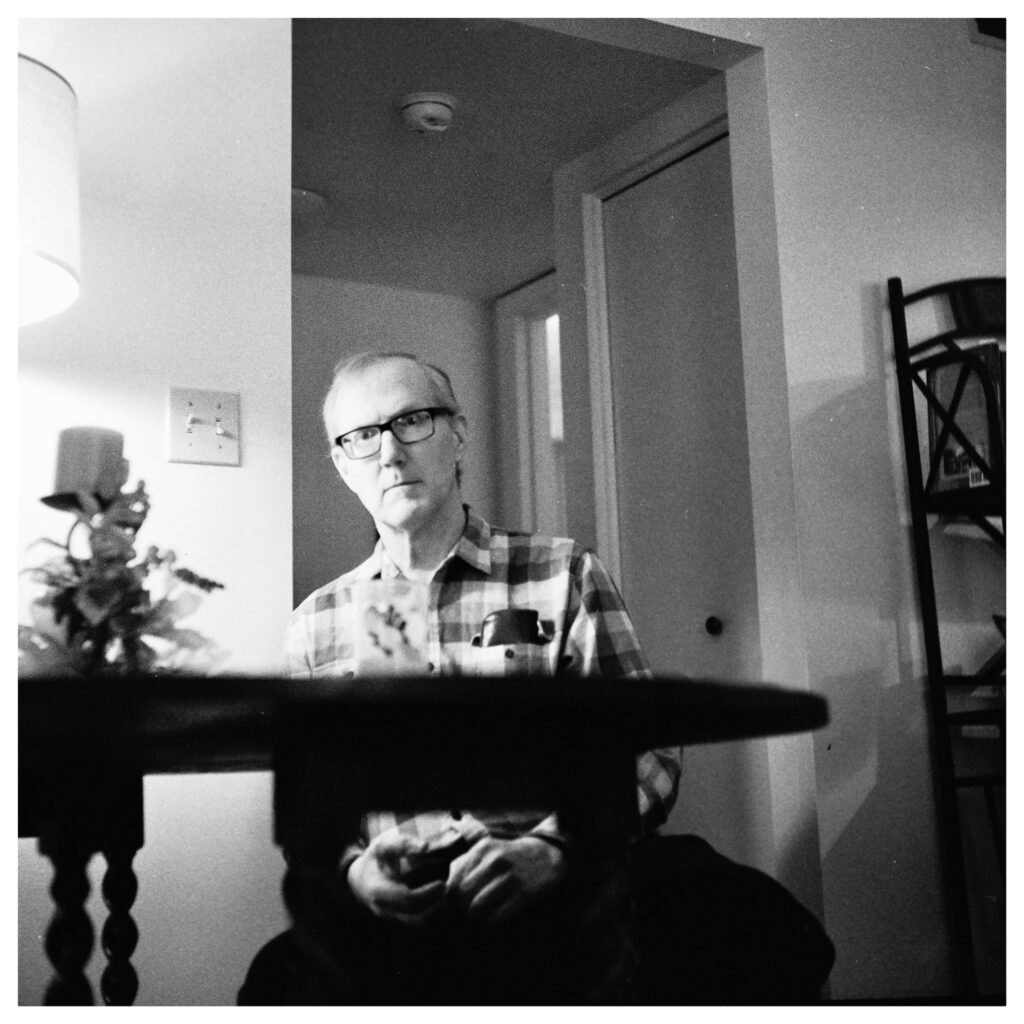

SCOTT: This last shot is such an interesting composition. It’s very close to something pretty familiar and conventional. Ok, it actually is a portrait, but there is something just a little ‘off’ about it. In a good way. The effect is not dissimilar to how I feel looking at the landscape with the bridge where everything is just a little off kilter in ways that draw me deeper into the photo. The low up angle with the tabletop splitting the frame and the ceiling closing everything in is very interesting, as is the unstudied stillness of the somewhat taciturn-looking sitter. It feels a little like you grabbed a frame on the sly while you were setting up. There’s a powerful sense of calm dignity and self-possession that reminds me of Grant Wood’s paintings, except perhaps for the wringing or fidgeting hands which would normally be framed out or unseen under the table. While the sitter might have a bit of a Grant Wood face, the portrait is not at all straightforward with its unusual upward tilting angle of the camera, and a very slight but perceptible lean to the left of the frame by the sitter. It’s not Dutch — I had to check the vertical line of the doorframe which is perfectly plumb — but it feels Dutch. And that table! There’s a kind of nervous energy subtext in both the sitter and, one feels, the photographer that makes this a very interesting moment — but also a bit inscrutable. One imagines not a lot was said during that photo session, but a lot is said quietly in the shot.

DAVID: Wow, very perceptive, Scott. I took this photo not long after getting back into shooting film in 2019. The setting is the living room of my mom’s apartment, and the sitter is my brother Jeff. I’ve taken any number of portraits of Jeff and my two other living brothers over the years — our fourth brother Kevin died in 2007 (an overdose, sadly) — and this is one of my favorites. It wasn’t formal in that I sat for hours planning the shot out, but neither was it fully spur-of-the-moment. I was fiddling with the Rolleiflex, taking a shot of my mom and my daughter at the other end of the room, but kept looking over my shoulder at Jeff, whose position behind the table and quietly curious expression called out to me. After letting him know I’d be taking a picture, I decided to shoot the frame from the waist, even though that meant that his body would be bisected by the table in the foreground. This tension-inducing, Friedlander-type gesture was more of an intuition than any grand aesthetic plan, but when I developed the film, I knew I liked it.

SCOTT: I like it too! Almost all of my favorite shots are intuitive grabs while I was planning to do something else. Indeed one of my goals as a photographer is to get fluent enough with the gear so that I can be in more of a ‘meditative state’ while shooting and be open to the telling moments that are unfolding in front of me, whether in a landscape, on the street or on the face of a person.

Well this has been far more interesting than I had any right to expect when I reached out to pitch the idea of a pair of “Five Frames” posts. Your photos opened up some pretty deep currents for both of us, I’d say. I really appreciate your willingness to share and your openness in talking about some of the home truths they reveal. I hope our readers have gotten something out of this too, but it’s meant a great deal to me and I thank you for it.

DAVID: Thank you, Scott! I have found our conversations incredibly meaningful — I don’t think I’ve ever had such an extended conversation with anyone about the photographs we take, or about the personal experiences that gave rise to them. What a luxury! I really appreciate your thoughtfulness and your incredible eye.

In conclusion I know we both hope that these two longer-form posts will prove interesting to 35mmc readers and that they will perhaps inspire other contributors to engage in and share the same kinds of conversations.

SCOTT: I’m glad you mentioned the idea that others in the forum might try out this kind of dialogue-driven post! I thought of it as a kind of virtual studio visit, and while we live only a few blocks apart in Brooklyn I love the idea that our fellow photographers from all over the world on 35mmc might be able to enjoy the kind of deep and freewheeling conversation we’ve had here.

DAVID: As with so many things in life, photography is better in community!

SCOTT: Amen!

Cover Photo: RAIL TERMINAL/HERITAGE MUSEUM, 2022, David Pauley, Rolleiflex 3.5F Kodak Tri-X 400.

Share this post:

Comments

Bill Brown on Five by Two: Two Photographers Look at Five Frames

Comment posted: 04/08/2025

I manipulate my images to my liking and I obviously don't have a problem with retouching, as long as it's done skillfully and thoughtfully. No guilt for letting an image be an underpainting for what you saw but letting the freedom of your final brush strokes be your vision.

Maybe someday I'll be brave enough to try something like this. Naw, I don't think so.

Thanks to you both for your insightful observations.

Comment posted: 04/08/2025

Comment posted: 04/08/2025

Gary Smith on Five by Two: Two Photographers Look at Five Frames

Comment posted: 04/08/2025

Not sure about the article "discussion" concept.

Comment posted: 04/08/2025

Comment posted: 04/08/2025

Curtis Heikkinen on Five by Two: Two Photographers Look at Five Frames

Comment posted: 05/08/2025

Comment posted: 05/08/2025

David Pauley on Five by Two: Two Photographers Look at Five Frames

Comment posted: 05/08/2025

Dean Lawrence on Five by Two: Two Photographers Look at Five Frames

Comment posted: 05/08/2025

However I doubt it is an idea I'd be too chuffed to take part of, even though I'm of similar vintage to yourselves, I'm still a novice in photography and a serious inferiority complex would have me hobbling to the hills.

Thank you both very much indeed for taking the time and effort towards such an excellent couple of articles.

Dean.

Comment posted: 05/08/2025

Comment posted: 05/08/2025

Comment posted: 05/08/2025

Wilbur Pauley on Five by Two: Two Photographers Look at Five Frames

Comment posted: 05/08/2025

I’m David’s brother Wilbur, and you both write brilliantly. Congratulations on both of the highly entertaining conversations!

Comment posted: 05/08/2025

Comment posted: 05/08/2025

David Hume on Five by Two: Two Photographers Look at Five Frames

Comment posted: 05/08/2025

1: Chapeau!

2: I don't think the idea worked well here - main reason being the amount of text vs. image and the relative cognitive times needed for each, and the fact that they need to be divided. (Compared say, to listening to a recorded conversation on a YT while looking at the images at the same time.)

3: Discussion/Critique is such a great thing. I know that people find it challenging but it's so worthwhile.

4: I could and should write of my own experiences of being part of the discussion/critique process.

5: I'll happily collaborate on either side of the equation to try something new here on 35mmc.

6: It is so valuable to do this! It's not a pass/fail exam it's a great opportunity to learn.

The last point is I think the most important. The hesitancy or reluctance of people to discus their work and their thoughts in public is natural, but it's such a great way to learn and grow in your practice. For example Dean's comment above - I'd say discussing your work is probably the most important thing you could do - flick me an image, we can discuss it, and it can be a secret or we can share it after!

In fact I used to do a series on my own website "1000 words" where I'd do this - here's an example wth a photographer I shared class with: https://www.davidhume.net/1000-words-alecia-williams/

Comment posted: 05/08/2025

Comment posted: 05/08/2025

Comment posted: 05/08/2025

Comment posted: 05/08/2025

Comment posted: 05/08/2025

Comment posted: 05/08/2025

Comment posted: 05/08/2025

Comment posted: 05/08/2025

Comment posted: 05/08/2025

Comment posted: 05/08/2025

Comment posted: 05/08/2025

Comment posted: 05/08/2025

Comment posted: 05/08/2025

Ibraar Hussain on Five by Two: Two Photographers Look at Five Frames

Comment posted: 07/08/2025

A great idea I'd like to see again!

Comment posted: 07/08/2025

David Pauley on Five by Two: Two Photographers Look at Five Frames

Comment posted: 08/08/2025