I was made in Hong Kong. I was born in Hong Kong in 1994, when the Union Jack was still on the Hong Kong flag. My mum is from Taiwan and my dad is a native HongKonger. Three years after I was born, China took Hong Kong back, and I was told that I am from China. In 2011, at the age of 17, I came to the UK and have lived here ever since.

It’s been a complex and confusing life journey. I showed up in a land ruled by a country on the opposite side of the earth, where people spoke a different language and looked completely different. I was raised in a society that spoke Cantonese, by a mother who spoke Mandarin. In my childhood, I struggled to learn 4 languages at the same time — English in school, Cantonese with friends, Mandarin with my mum, and Taiwanese dialects when I visited my grandparents. Then, in my teenage years, the Hong Kong government began following China’s guidelines, requiring every student to learn Mandarin — the standard Beijing version, which was different from the one I had already learned. Just a few months before I turned 18, I stepped back to the country that I was born — a land I had never been to before — and found myself surrounded by unfamiliar faces and ethnicities. My obsession with cameras began shortly after that.

Like many people in this community, I’m fascinated by different features of mechanical cameras — from the Leica M series, Hasselblad 500 series, Rolleiflex, Contax, Nikon F series, to point-and-shoot and folding cameras. But now I’ve reached a point where I’m searching for the historical and philosophical meaning of a camera — a camera that represents an image, a mission, and, most importantly, an identity.

The Diana camera was made in Hong Kong during the 1960s and 1970s. The name “Diana” has nothing to do with Princess Diana; the manufacturer was called the Great Wall Plastic Factory. Diana and Great Wall — even just the names remind us of two countries and the only place they intersect. Back then, Hong Kong wasn’t the luxurious, shiny, high-income city people know today. It was a city full of corruption, illegal immigration, and water shortages — a place where people struggled to make a living while also serving as the world no.1 plastic manufacturing hub.

The Diana camera wasn’t created out of innovation or artistic ambition like Nikon, but because it’s cheap and easy to make. The Great Wall Plastic Factory, struggling in the competitive and declining plastic-processing industry, reinvented itself as a camera manufacturer to fulfil a new order from a U.S. candy company — a camera meant to be given away as a promotional gift. That deal saved the business, and soon, Diana cameras were being exported to Europe, including the UK.

Funnily enough, I found my own Diana here in the UK on eBay, half a century later. The moment I unwrapped it from the box, it felt like a reunion — especially because it was manufactured in Kowloon, the very district where I was born. It’s around the same age as my father, and it travelled the same route that I did — or perhaps I should say I travelled the same route like it did.

The Diana is an all-plastic camera — from top to bottom. The lens, the viewfinder, the body, the knob, even the strap are all made of plastic. It has 3 apertures, 2 shutter modes, zone focusing, and takes 4×4 cm images on 120 film. It wastes a lot of space on a roll, but that design helps reduce vignetting. That’s it — cheap, light, unbreakable and do the job.

I can’t stop seeing myself reflected in this camera, because every part of it seems wrong and right at the same time. A camera made in British Hong Kong, by Cantonese people, under a company name that symbolizes China. It was made for Americans, and now it has found its way into my hands in the UK. But does that matter? The long-lost history of this camera has little to do with its survival. After all, it doesn’t matter who it was made for, why, or where. It still takes pictures on 120 film — and that’s the crucial part. Being useful is the key of bearing a colourful history, and my life is the same.

During the 1970s, 35mm film began to dominate, and 120 film started losing popularity. Other manufacturers quickly copied the Diana’s design. Meanwhile, Hong Kong was transforming into a global financial centre. The Great Wall company stopped producing the Diana and shifted industries again — this time, to making magnifiers.

This is a story about survival, adaptation, and resilience. Diana is a symbol of Hong Kong’s history — it comes and it goes. It wasn’t meant to be, but it succeeded nonetheless. Hong Kong has gone through different peoples, industries, and systems — and, to quote one of my favourite verses from the Bible:

“The thing that hath been, it is that which shall be;

And that which is done is that which shall be done:

And there is no new thing under the sun.”

— Ecclesiastes 1:9

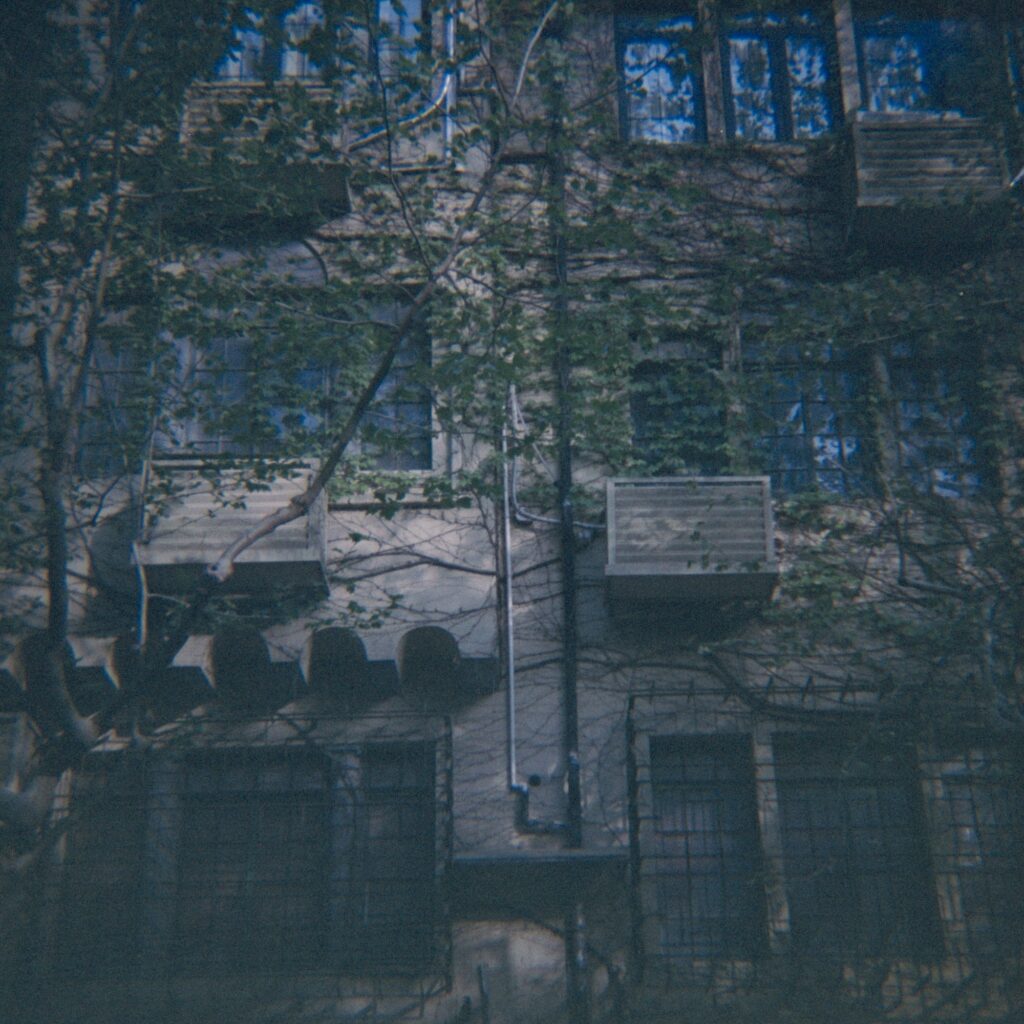

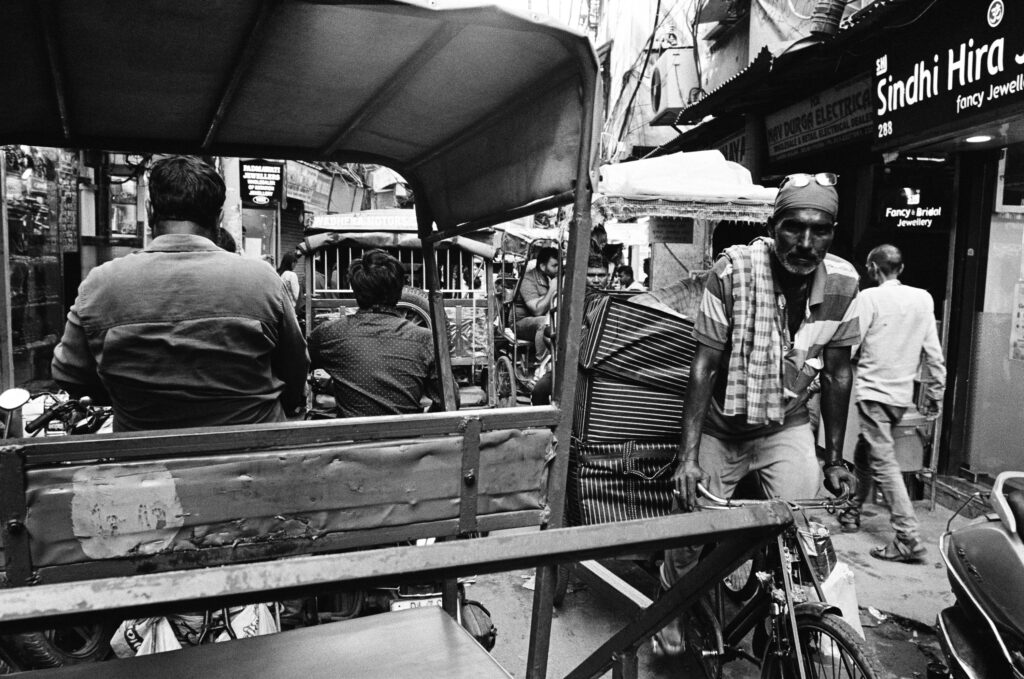

(Photos taken in the UK and China)

Diana | LomoChrome Color ’92

website: www.ssilencioo.com

instagram: www.instagram.com/ssilencioo.rd

Share this post:

Comments

Erik Brammer on Made in Hong Kong

Comment posted: 12/11/2025

Alastair Bell on Made in Hong Kong

Comment posted: 12/11/2025

Why you ask? Because in February I shall be giving a talk at my photography club about my photographic journey and arguably it started right there with that toy. Its due to arrive tomorrow and frankly I can't wait!

I would like (with your permission) to use your first image to illustrate the quality of image the famous Diana produces since I have none of my own.

Thank you for writing this piece - its extremely timely!

Comment posted: 12/11/2025

Comment posted: 12/11/2025

Thomas Eland on Made in Hong Kong

Comment posted: 12/11/2025

After 25 years in the army I retired in 1992. The final three years i served in Hong Kong in Fanling with the Gurkhas. They rode BMX bikes along the border keeping out illegals. I enjoyed that time, my first taste of Asia. I visited the walled city and only flew in and out of Kai Tak. I remember a big camera shop in Hong Kong island on a street of stairs where I bought several additions to my Pentax system, the LX, 67 and 645.

I've never been back....probably changed out of all recognition.

Christopher Welch on Made in Hong Kong

Comment posted: 12/11/2025

Nicholas Clarke on Made in Hong Kong

Comment posted: 12/11/2025

Hong Kong has an earlier history of camera making. Haking made high quality cameras in the 1950s and 60s and they were imported into the UK. My first camera was bought in 1960 and was a Halina 35X made by Haking. It was a 35mm camera with an anastigmat lens, variable aperture and a range of shutter speeds. I still have family photos from that time that I have digitised and am impressed by the quality.

Incidentally at that time Hong-Kong-made goods were marked 'Empire Made'. Those from Japan were marked 'Foreign'!

Ken on Made in Hong Kong

Comment posted: 12/11/2025

Geoff Chaplin on Made in Hong Kong

Comment posted: 13/11/2025

Thanks for the story and good luck!

Alexander Seidler on Made in Hong Kong

Comment posted: 13/11/2025

Scott Gitlin on Made in Hong Kong

Comment posted: 22/12/2025