The Kodak 35RF has an interesting development story very much bound up with the Second World War. The conflict isolated the major camera and lens producers and accelerated development in other parts of the world as a consequence.

For some time I have wanted to try this Kodak model, a unique camera that has always given me the impression of being more of a prototype than a finished product. Researching it, however, I discovered that it was in reality rushed into production in 1940 to compete with cameras like the Argus C that were appearing at the time in the US. The rushed introduction no doubt contributed to its appearance mainly because it is built around the solid Bakelite body and film transport of the much less advanced Kodak 35 model from a few years earlier. That camera didn’t have a rangefinder so a new top plate and rangefinder/viewfinder was added on the outside. It sold well until 1951 and was a reliable performer from all accounts.

Interestingly, at the other end of the quality spectrum the Kodak Ektra was also in development in the US around the same time. This was a very advanced 35mm interchangeable lens, magazine back model made between 1941 and 1948 with an innovative, zoom finder system and a range of lenses and accessories. The development of the Kodak 35RF must have shared some aspects with the Ektra, the view/range finder arrangement being very similar. However, the Ektra is as different a camera as could be imagined and well ahead of its time. Its complicated, early technology made for very involved operating procedures however, reading the user manual. A major factor must have been that there was no access to the Retinette/Retina ranges and other advanced systems during WWII of course other than secondhand donations, like the British requests for the public to hand over their Leica and Zeiss cameras for the war effort.

The camera

Viewfinder on the left, rangefinder on the right.

The back of the Kodak 35RF showing the tiny finder/rangefinder eyepieces that I initially found difficult to locate with the camera to my eye.

There was one thing that really surprised me on first handling it. I had looked at the instruction manual on the invaluable Orphan Cameras web site and noticed a somewhat contradictory suggestion not to hold the finder too close to the eye in order to see the whole frame. Even wearing glasses this works amazingly well so the finder must have an optical design with unusually high eye-relief, possibly influenced by the Ektra. The image is rather small, similar in physical size to many others of the time, but its coverage is a definite plus for a camera of this era though centring your eye is essential for precise framing.

This particular camera is in good cosmetic condition for a product made nearly 80 years ago. There are signs of age but not heavy use with minor corrosion affecting some bits and rust on one screw head below the shutter release (sweaty fingers) but no marks from heavy wear. Just one niggle around the focus, see below.

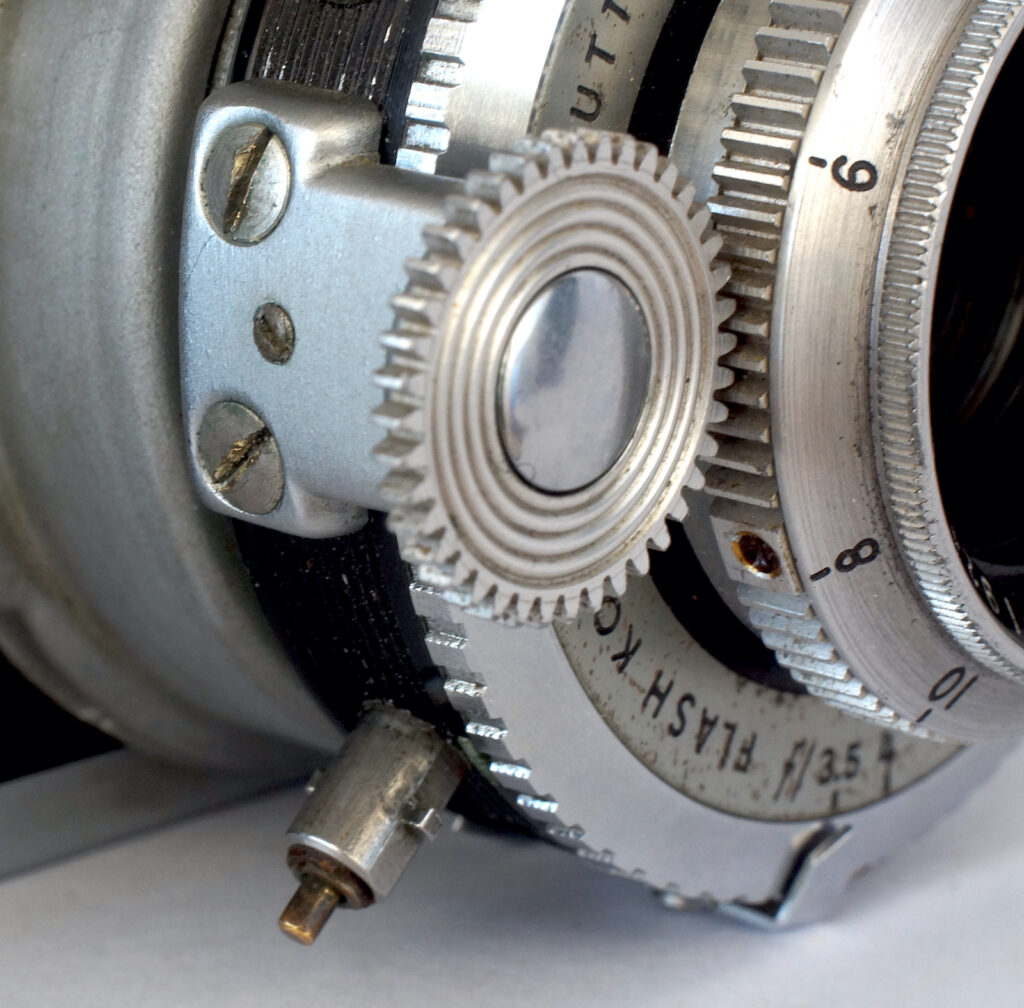

The lens serial number places it as coming from late in the production run in 1949, according to Kodak’s CAMEROSITY, 1 to 0, coding system and based on the ET prefix of the lens serial number. Is this where Hasselblad got the idea for his VHPICTURES coding system? Hasselblad was Kodak’s agent for Sweden after all. It has the f3.5-f16 Kodak Anastar in the later Flash Kodamatic shutter with a proprietary flash connection. The delayed action fitted to earlier versions is replaced here by a similar cocking mechanism used to arm the flash synchronisation gears. The earlier versions had no flash sync. and had to use the open flash technique with the camera on a tripod, opening the shutter on bulb, firing the flash manually, then closing the shutter.

The flash sync lever tucked away under the top housing.

The Kodak 35RF lens seems to promote some debate from what I have read suggesting it may be a four element but confusingly not of a Tessar design if so. It has 6 clear reflections indicating three elements or four if it contains a cemented pair like a Tessar. Four seperate elements, like a Double Gauss, would have eight reflections. A mystery but it is the results that matter after all and they are very acceptable.

The inset shows the equivalent of a detail from an image around 80” x 30” or 2m x 0.8m at 72dpi screen resolution. No sharpening has been applied.

The lens showing six reflections. Some dust but clean and free from problems.

It is a pretty heavy camera using a solid Bakelite moulding for the main body carrying aluminium, steel, glass and plastic components with a leatherette-like finish which seems to be moulded into the body.

The cluster of controls around the Kodak 35RF wind-on. The chrome button is the interlock release, scratched because it is easier to press with a fingernail, being so tight to the wind knob.

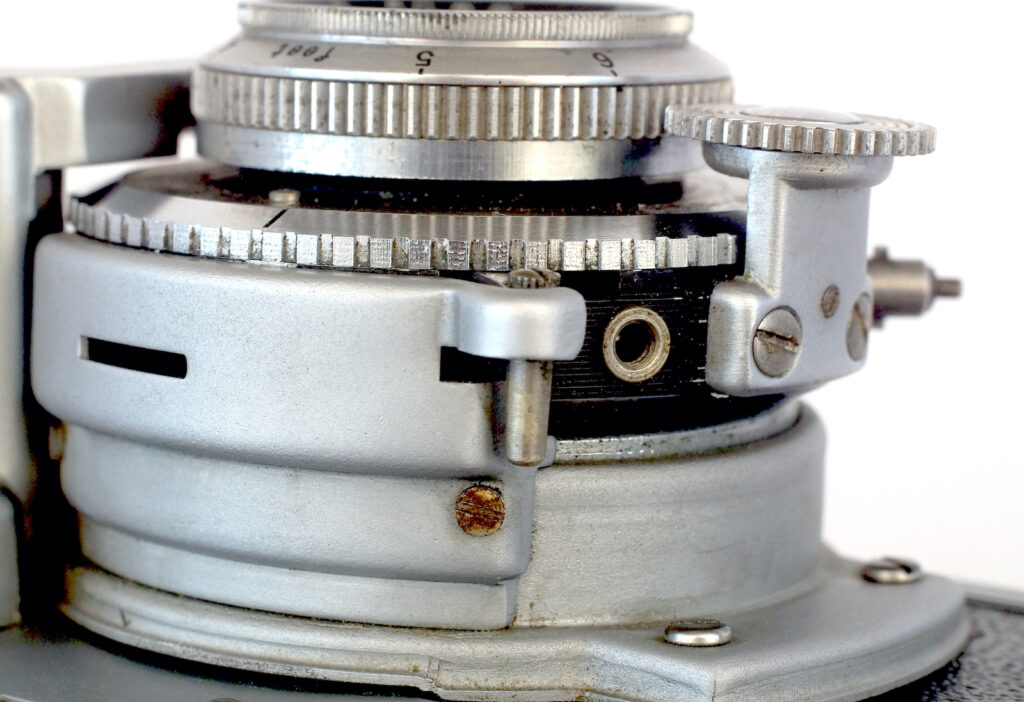

Basic wind on requires a button to be pressed after each exposure to release the counter interlock. The button is confusingly located where a shutter release would normally be. Wind-on is by a plastic knob which winds clockwise rather than anti-clockwise, taking up the exposed film with the emulsion side outermost. This probably serves to ensure the sprocket holes firmly engage with the cog wheel.

Spacing is very tight and the wind on must be continued after a click is heard until it stops. Stopping just after the click will cause frames to touch or even overlap a little. This may just be afflicting this camera or the type in general.

To rewind, the wind knob has to be pulled up to disconnect it and the metal rewind knob turned conventionally to return the film to the cassette. On rewinding, ratchet sounds accompany the process, coming from the gear at the top of the take up shaft, visible in the detail of that part, see below. A small counter disc is located alongside the wind knob and must be set to #1 after the usual two blank exposures. It stops turning when the film is almost fully rewound. The manual recommends turning the rewind a few more times to avoid any chance of fogging the first frame or two. In fact it only stops when the film leader passes the sprockets so fogging is unlikely, avoiding winding the whole film back into the cassette. This is all inherited from the 35 with hardly any modification.

The shutter release bar is almost obscured below the shroud over the top of the shutter, not immediately obvious but unlikely to be pressed accidentally. It has a very light action. The slot to the left is where a red line appears when the shutter is wound with the flash connection protruding at 7 o’clock.

Just like the Voigtländer Vitos, the Kodak 35RF will only work with film loaded, the film’s sprockets driving the shutter cocking mechanism.

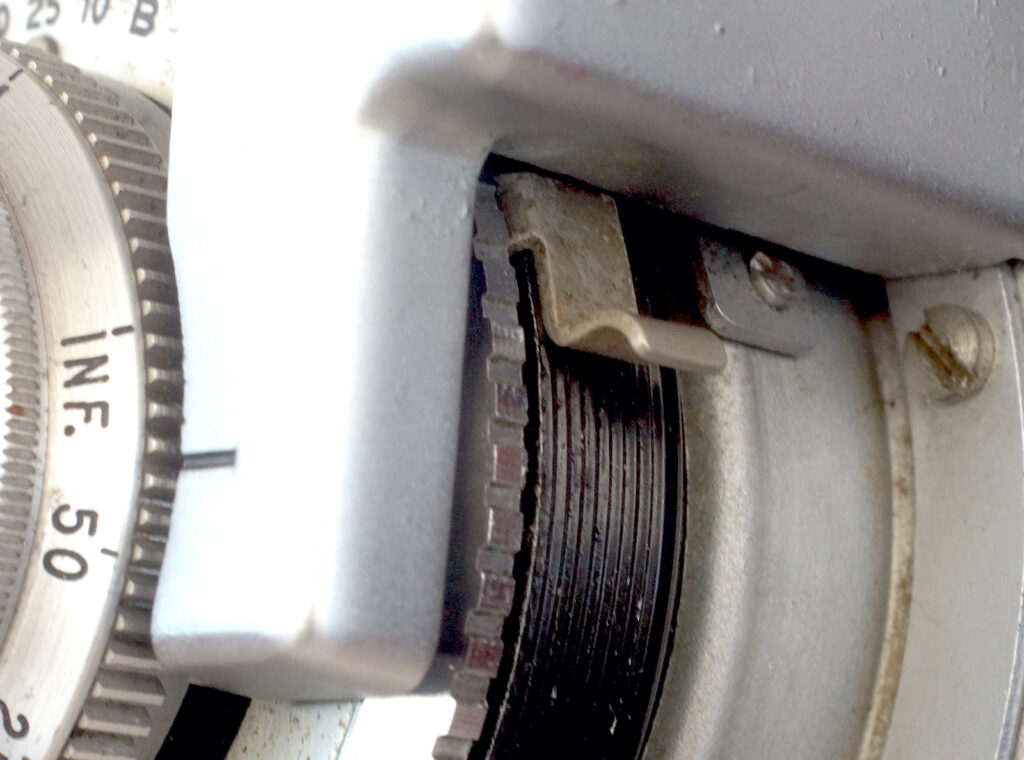

Detail of the focus wheel mounting with the three screws mentioned.

The serrated focus wheel was very stiff when I received it but I managed to adjust it to work smoothly. There is a tiny screw between the wheel’s attachment screws that controls how deeply the cog seats in the focus ring’s gear. This screws in to bring the cogs apart after backing off the large screws which are tightened once you are happy with how the gears are meshing. Someone had logically, though incorrectly, unscrewed it in order to move the gear away from the focus ring which only serves to tighten it more. Quite a puzzle until I twigged how it worked.

Now the focus niggle mentioned above. The two grub screws that are usually used to loosen the front element in order to adjust the focus setting are immovable but don’t seem to be tight enough to fix the focus securely in place so care is needed not to turn the focus ring past the end stops. I must have done this at some point because my second film, an Ilford FP4+, was all focussed way too close. Correcting it was not difficult if rather Heath Robinson, simply reversing the process at the opposite end to the original overshoot. This more or less fits in with the Pheugo web site advice to adjust the rangefinder in a similar way but after loosening the grub screws.

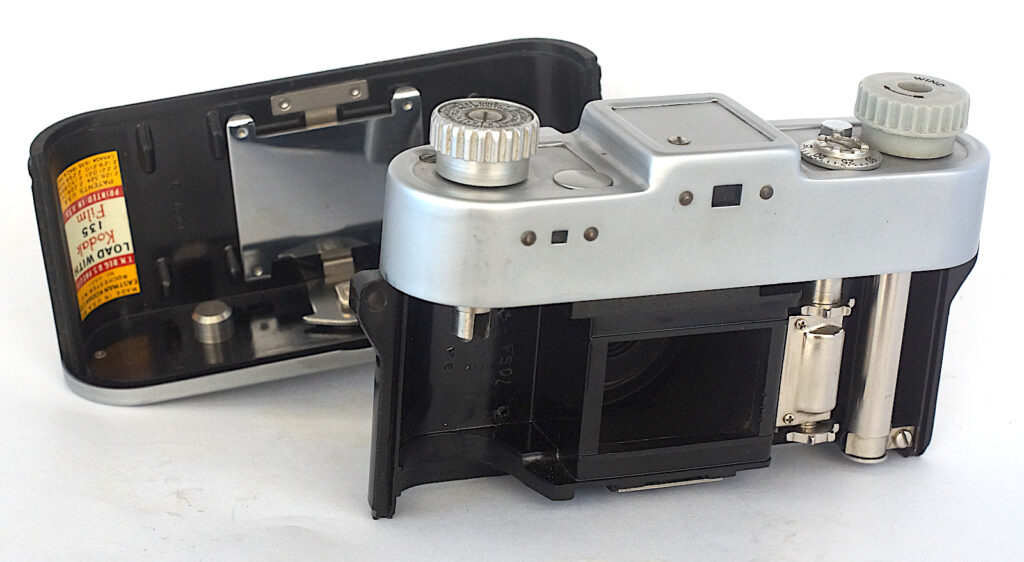

With back off, the mirror like pressure plate is visible.

Another thing my researches turned up was the pressure plate. It has a mirror-like polish and no blackening so using film with an anti-halation layer is essential, limiting choice of film types. I also suspect it is the cause of the edge vignetting in some images.

A detail of the take up spool and counter arrangement. The quality of the materials used and of its construction are clear and the ratchet gear on the top end of take up spool is visible.

Unsophisticated design matters apart, the quality of materials and manufacture are excellent. Nothing seems to have been skimped anywhere. Probably developed quickly, initially in order to take on the competition and then to compete for military contracts (there was apparently no retail production between 1941 and 1944) so reliable performance and durability would be a high priority.

Results

After several dry runs with an exposed test film, I loaded some part-used ISO 400 Fuji colour neg into the Kodak 35RF and ran off a few frames. The film had stood on a shelf all through a rather hot summer which unfortunately producing some ugly colour so I have converted these to mono.

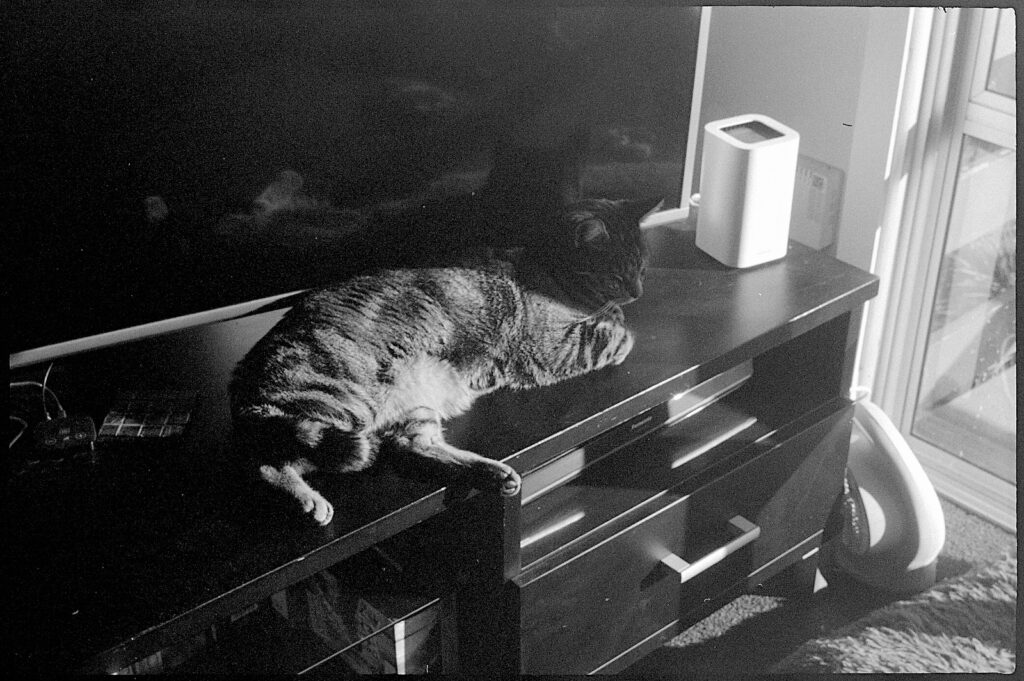

Our two cats have such a hard life finding suitable places to have a nap.

His brother prefers a softer surface to recover from playing with their toys.

The number plate of a locomotive, once used on New Zealand Railways and now preserved at Dunedin’s Toitu Early Settlers Museum.

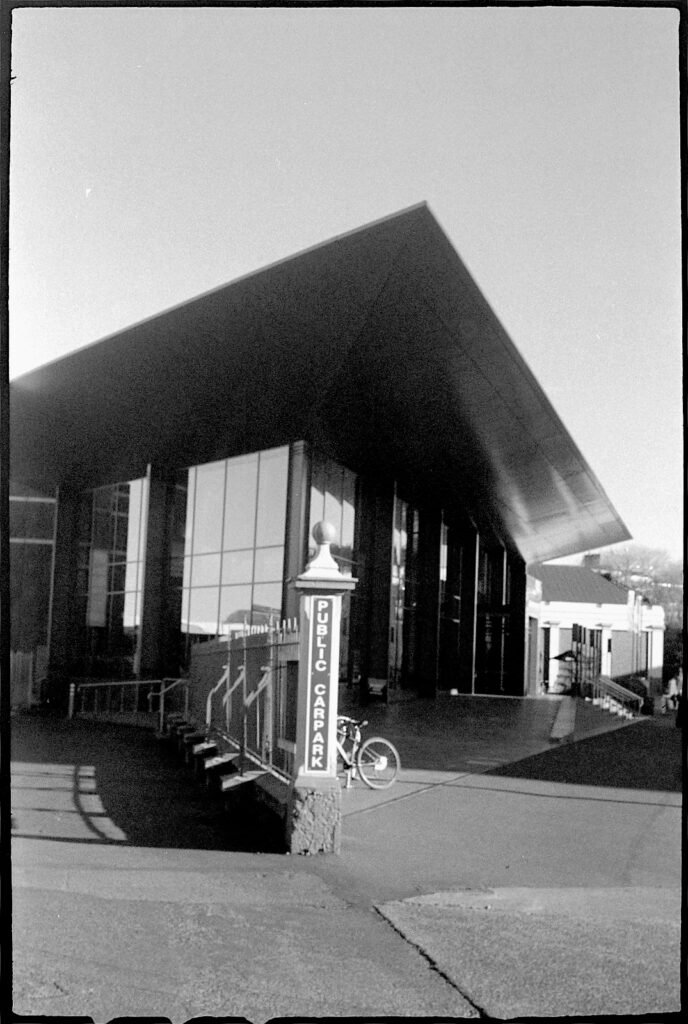

The imposing modern extension to the museum. The small finder makes careful alignment difficult.

Following the FP4+ out of focus disaster I shot a few frames on Rollei 80S to check things were OK again. I am pleased to say that they are. Focus is pretty accurate and lens performance up there but I did get a smidgeon of camera shake on one or two, my fault of course, my excuse being the rather awkwardly placed shutter release. So with care the camera is a capable user as well as a characterful display item, something of a Beauty and the Beast kind of attractiveness.

These are much better examples of what the Kodak 35RF can produce.

A check shot focused with the rangefinder on the handles at f4.

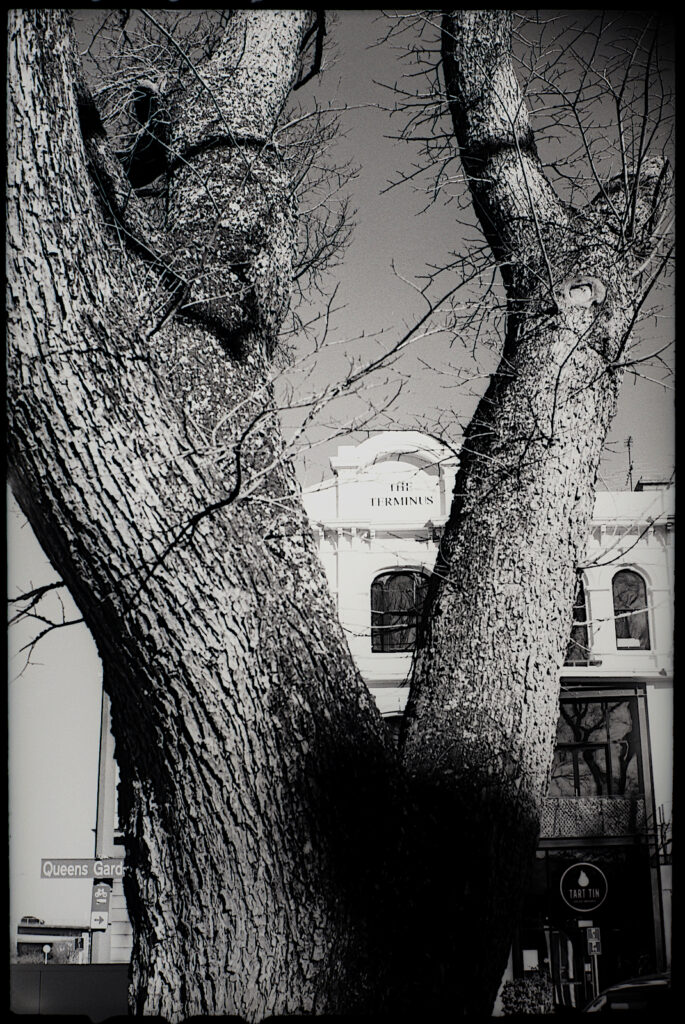

At infinity and again at f4 so not the optimum aperture but sharp enough. The vignetting around the edges of the frame are intriguing and I wonder if the effect is something to do with the mirror-like pressure plate. It is most noticeable in very bright shots like this.

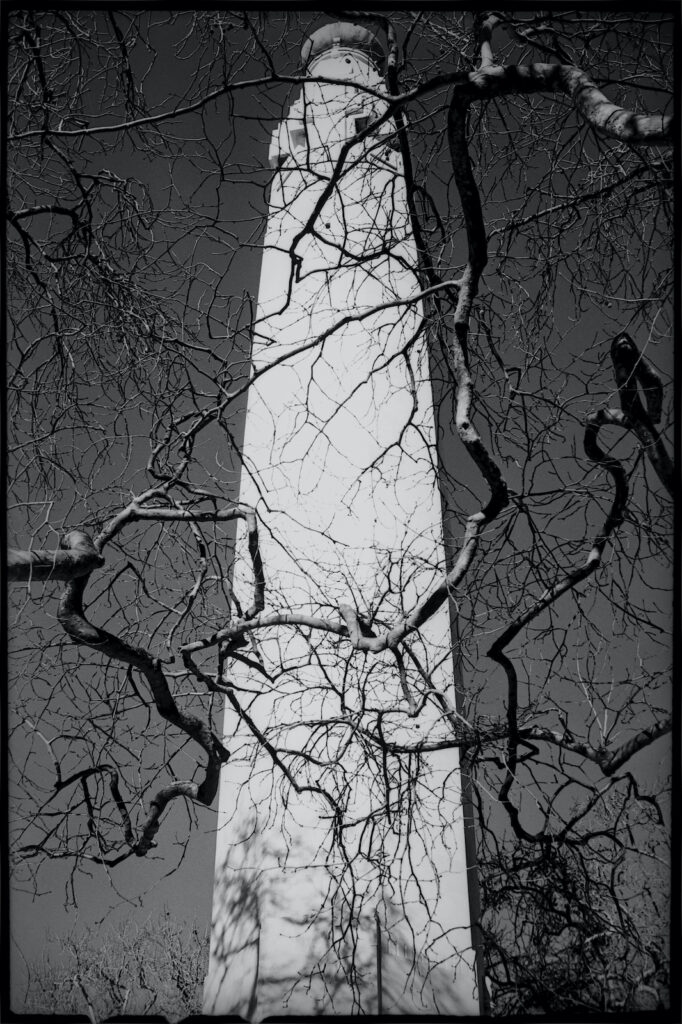

Base of Queen Victoria’s monument with Dunedin’s Cenotaph beyond.

The Cenotaph through bare winter branches.

Entrance to Dunedin’s Chinese Gardens. An example of my problem keeping things level with the tiny finder and also accurate framing. The moon was visible at the very bottom of the frame and the structure just clear of the top so my eye must have been off centre.

One wing of the New Zealand Railways bus station, now part of Dunedin’s Toitu Early Settlers Museum. This is the same image as the one above but with a small amount of sharpening applied.

One of the converted commercial buildings in the original business area.

These shots have cheered me up no end after the FP4+ wash out. And the lens isn’t too bad, whatever its construction. I have now seen a suggestion it is a triplet but whatever it is it gives a good account of itself.

Conclusion

All in all, the superficial impression of something in development needing more work to refine the design is more likely the result of marketing demands in 1940, yet the Kodak 35RF is somehow quite satisfying to use once thoroughly familiar with where everything is. The finder plus the wide base rangefinder’s large window with the whole image being split horizontally, makes it easier to use than a central spot in the main finder. Ergonomically, though, it excels as a “how not to” example. The wind knobs and the focus wheel are the only things that fall intuitively and easily to hand. It is a practical, well made instrument for all that.

It really is a curate’s egg of a camera, good in parts. The design reflects the “needs must” pressures that must have prevailed at the time when the skills of the Stuttgart camera makers were not available to Kodak. I could see this being a Retinette with coupled rangefinder for instance. US designed models always had their own design character though so maybe there wasn’t much cross fertilisation in any case.

Share this post:

Comments

Michael Zwicky-Ross on Kodak 35RF coupled rangefinder from 1949.

Comment posted: 19/09/2025

Comment posted: 19/09/2025

John Andrews on Kodak 35RF coupled rangefinder from 1949.

Comment posted: 19/09/2025

Comment posted: 19/09/2025

Kodachromeguy on Kodak 35RF coupled rangefinder from 1949.

Comment posted: 19/09/2025

Comment posted: 19/09/2025

Gary Smith on Kodak 35RF coupled rangefinder from 1949.

Comment posted: 19/09/2025

Looks like an odd duck!

Comment posted: 19/09/2025

Russ Rosener on Kodak 35RF coupled rangefinder from 1949.

Comment posted: 19/09/2025

Once Kodak Stuttgart was back up and running and produced the fantastic Retina II models no doubt Kodak decided why compete with yourself? The much better domestic made follow on to the Kodak 35 is the superb little "Signet 35" which came out around 1951. It also was originally produced for the US Military but became popular in its day. Later Signets were not nearly as good.

Comment posted: 19/09/2025

Alexander Seidler on Kodak 35RF coupled rangefinder from 1949.

Comment posted: 20/09/2025

Comment posted: 20/09/2025

Jeffery Luhn on Kodak 35RF coupled rangefinder from 1949.

Comment posted: 20/09/2025

I was impressed with the quality of the shots and the determination it took to achieve them. A great collector item. I have never seen one before.

You mentioned the Argus 'brick', which just may be the ugliest camera in the world. I get a lot of donations to the college where I teach photography and we've collected 10 Argus cameras in various stages of decomposition. I have to say, Argus Bricks do not die easily. Even some that are caked with dust and rusted often still operate well and produce decent photos. While the Kodak 35RF is a wonder of features and goo-gahs built on top of each other to create a piece of unique industrial beauty, the Argus Brick is a functional...uh...brick. What a boring world this would be without these vastly different objects!

Comment posted: 20/09/2025