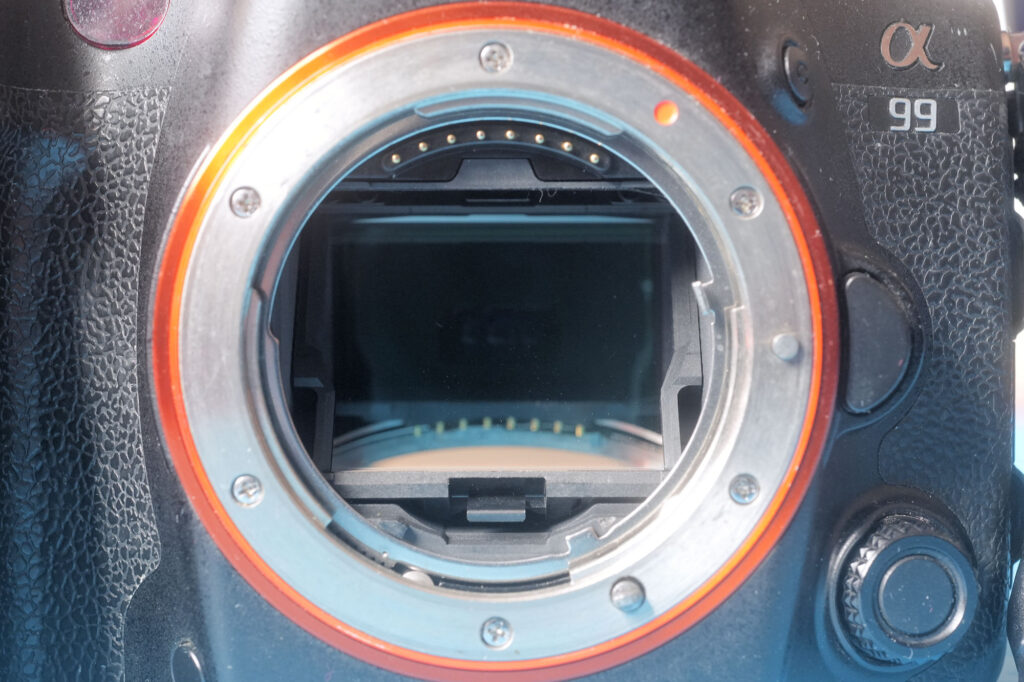

In late 2012 Sony produced a full-frame mirrorless camera. The Sony A99.

For some time, Sony had been hedging its bets with regards to digital cameras. It had long produced video cameras and been one of the first companies to develop digital stills cameras with their Mavica and Cyber-Shot lines. Sony had adopted and absorbed the Konica Minolta photography division back in 2005. It had reissued a whole bunch of Minolta lenses (many of them full frame) in A-mount, which fuelled speculation that they would, at some point, release a full-frame camera.

It appears that Sony were intent on bringing in ‘disruptive’ technology to an industry that may have been hoping that digital was as disruptive as it would get.

In 2008 Sony introduced their expected full frame A-mount DSLR – the A900, challenging the duopoly of Nikon and Canon. It wouldn’t be the last time they tried to shake up the market. At the time, the camera was actually criticised for having too many megapixels (24).

Halfway through 2010 Sony introduced a new interchangeable mount for their (heavily Cyber-shot influenced) NEX mirrorless (and at the time, viewfinder-less) cameras. A few short weeks after, they introduced a pair of mirrorless-but-not-mirrorless SLT cameras: the A33 and A55.

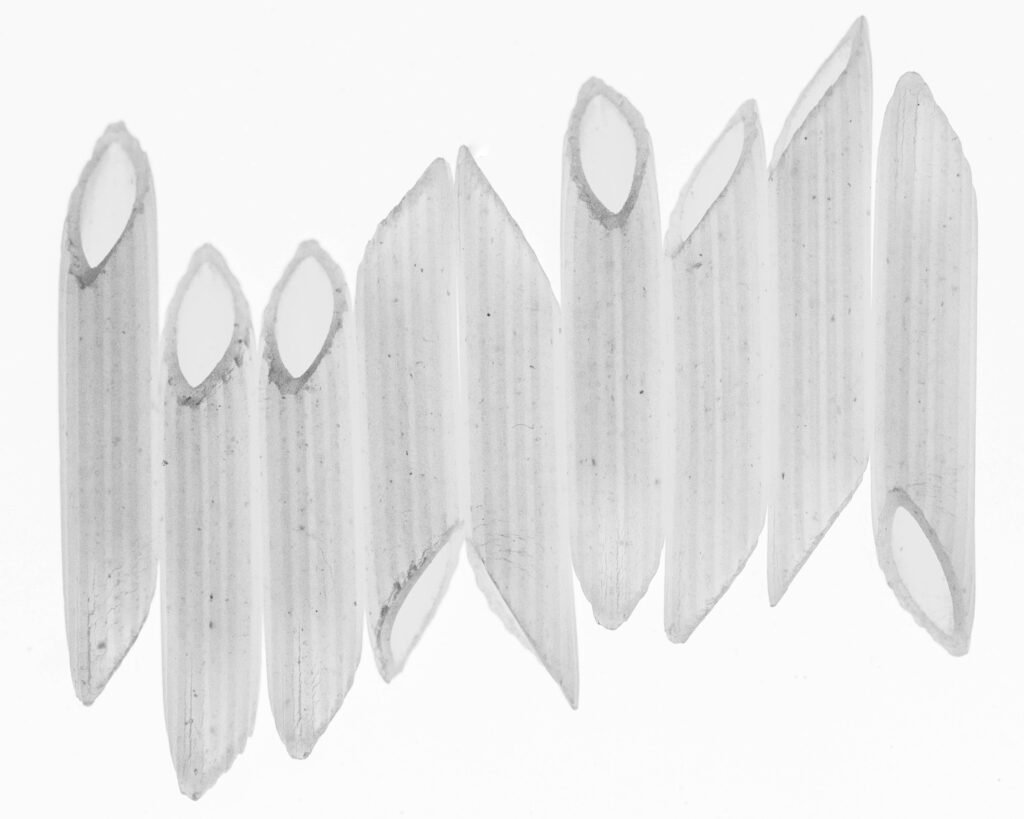

Single Lens Translucent (SLT)

Translucent was a bit of a misnomer, as the thin plastic beam-spitter is transparent, rather than translucent. Lots of people pointed this out at the time, but Sony stuck to their guns (and terminology).

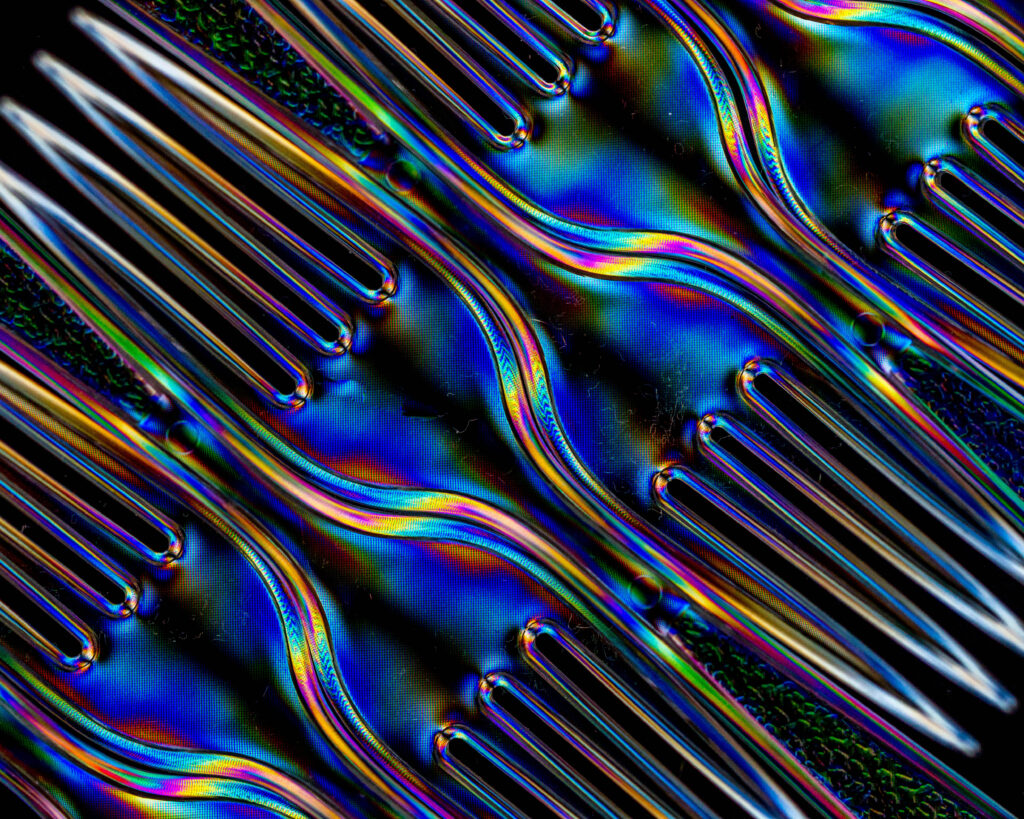

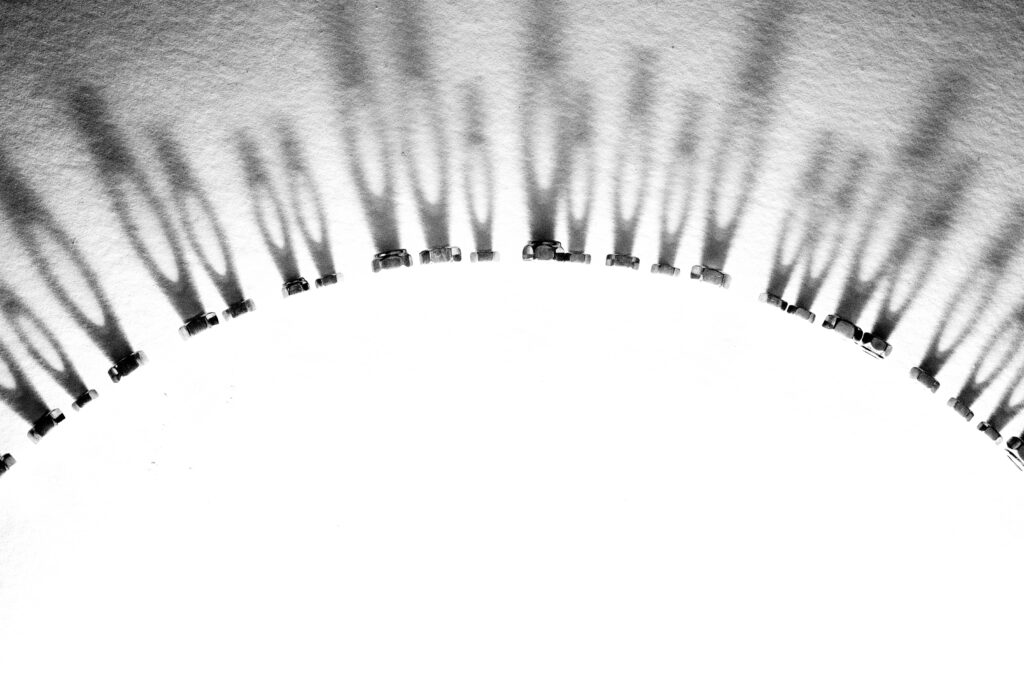

The A33 and A55 were entry-level and mid-range APS-C cameras using an electronic viewfinder which used a feed directly from the sensor. In front of the sensor was a thin beam splitter, which deflected a portion of the light to a set of phase-detect AF sensors, which controlled focus. You could shoot stills and video without the mirror moving.

There were a number of advantages for Sony in SLT technology:

- In the absence of on-sensor phase-detect, SLT allowed them to offer accurate Autofocus in real time, while taking a live feed from the sensor.

- You could get good video directly from the sensor while being able to adjust focus automatically.

- You can overlay information (such as focus peaking) on the viewfinder/rear screen.

- It was solid-state with fewer moving parts. Less wear, less to go wrong, less to need complicated assembly and calibration. Less cost.

The disadvantages were:

- You lose about 1/3 of a stop of light to the sensor

- You lose some traditionalists who will have a conniption fit over the idea of using an electronic viewfinder.

Sony tried to reassure SLR traditionalists that they were planning to run SLR and SLT side by side while both were viable. They released a pair of equivalent dSLRs at the same time.

It had all been done before

The technology was not new. Canon had used a similar semi-transparent pelical mirror to feed a viewfinder while allowing the remaining light to pass onto analogue film back in 1965. They called it the Canon Pellix. The bonus for them had been phenomenal (for the time), continuous shooting rates, at the expense of a loss of light to the viewfinder and film (as the light was split between the two). Canon reused the idea for the Analogue EOS RT and EOS 1N RS.

Three fish in the water/irons on the fire

In 2012, Sony were offering three flavours of interchangeable lens camera –pure mirrorless with a tiny registration distance (using single figure numbers), a traditional SLR offering phase-detect AF (using three digit numbers), and this new, strange hybrid (using 2 digit numbers), which used A-mount lenses in combination with an electronic viewfinder, but which used phase-detect AF, adjusted in real time via a beam splitter.

Writing on the wall

Sony were never going to run with three separate systems long term. The first of the three Sony options to be dropped were the SLRs. The A560 and A580 that were released along with the A33 and A55 did not get replaced when those models reached the end of their product lives. They were the last Sony SLRs. Cameras like the a700, a900 and a850 had sold well to Minolta die-hards and those who were inclined towards the road less travelled (ie not Canon or Nikon), but a fair few had dipped their toes in E-mount and SLT waters as well, and had lost a degree of resistance to electronic viewfinders. Nevertheless, some die-hard A-mount users switched to Pentax or Nikon at this point.

The big sign that SLT was winning hearts and minds was the A77 in 2011. This was an SLT replacement for the A700 (a much loved camera in the community). It used the same 24MP sensor as the mirrorless NEX-7, but it took A-mount lenses. The A77 gave an amazing amount of information in the viewfinder and it took stunning photos. I was on the administration team for Dyxum at the time and the A77 went down surprisingly well with a good proportion of the membership.

The Sony A99

The Sony A99 was a Pro-spec camera using a full-frame 24MP sensor. It had a whole system of respected lenses. It could shoot 6 frames per second while maintaining autofocus, It offered IBIS which was rendered more effective because of the absence of a moving mirror and the use of an electronic first curtain shutter, which made it less prone to camera-induced shake to begin with. It had an optional vertical grip that could take an additional two batteries in addition to the one in the body. It was highly customisable. It had a fully articulating screen that could be viewed from any angle behind or to the side of the camera. It could also be aimed forward so that the subject would see themselves or over the viewfinder ‘hump’ for a ‘selfie’. It had an electronic viewfinder that could overlay whatever information the photographer desired, including focus peaking and an electronic level. It also featured an electronic focus limiter, which allowed you to set minimum and maximum limits of focus with any lens.

Aesthetics

You will sometimes hear people talk about Minolta DNA in connection with Sony A-Mount cameras. The old Minolta camera division certainly was highly influenced by the needs of photographers and the way in which technology could be used to bring them excellent photographic images. However, their cameras were sometimes aesthetically challenged. I’m thinking of the likes of the X1/XK/XM, Dymax/Maxxum/Alpha 9xi and Dynax/Maxxum/Alpha 800si; wonderful cameras, but a bit ugly.

This seems to have come to a head with the A99, which may well be the ugliest camera that Sony ever conceived. How Dreamworks didn’t sue for resemblance to ‘Shrek’, I simply don’t know.

Downsides

The Sony A99 used the same AF unit as the A77. For an APS-C sensor the array was quite generous, but on full frame all the focus points sit well within the central third of the viewfinder.

I remember being mildly troubled by a slight creak in the door under my right palm when I first owned the A99. The soft rubber around the eye-cup tore and there is now no evidence of it. Other rubber parts have worn or torn over time.

Although the splatter finish on the Sony A99 is robust, when it wears through, you see the grey magnesium alloy shell. The wear just doesn’t look as attractive as what you see on older black bodies with a brass top-plate.

Did I mention that it is a bit ugly?

A view around the Sony A99

The ‘AF range’ button gives access to a nice feature. Press it and you get a bar at the bottom of the screen showing distances from macro to infinity. By turning the front and rear control wheels, you can restrict the focus range at either end of the range, regardless of whether the lens you have fitted has its own focus limiter.

GPS was standard on the A99, but was omitted in models for some markets.

In a bizarre twist Hasselblad announced their HV in 2014. This was a re-skinned A99 with added bling. The price was in five figures at release. When Hasselblad saw how ridiculous the HV was, the remaining stock was sold off far cheaper.

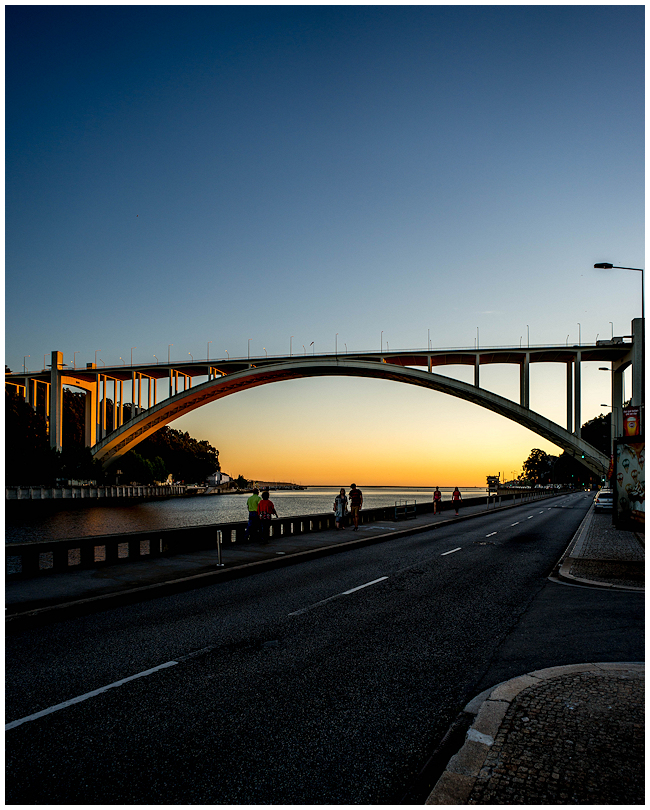

I stress this camera has travelled with me across continents. For my courier trips I’m limited to cabin luggage, so three changes of shirt/underwear/socks, plus what ever else can be stuffed into a carry-on backpack. Before lockdown put a pause on my courier globetrotting, the A99 was my standard camera.

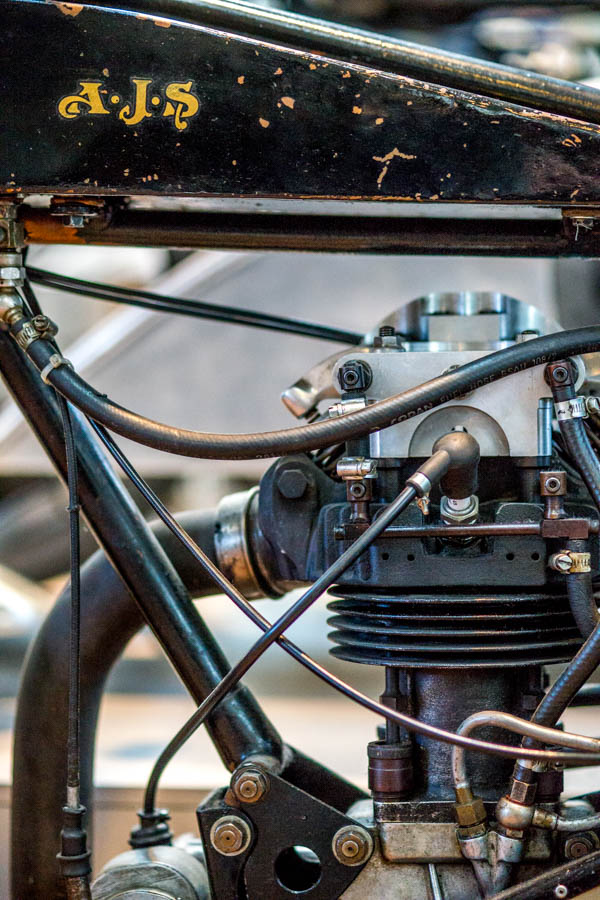

Pictures from the Sony A99

The user experience

Looks aside, the Sony A99 works very well. I was sceptical about SLT from the start (chalk me up for a slight Luddite tendency) – I really didn’t like the idea of shooting through something that could attract dirt and dust as well as stealing some of the precious light coming through the viewfinder. However, I had been seduced by the lovely (for 2012) viewfinder of the NEX-7, which I had picked up as a travel camera. It gave all the overlays you could want, gained up to compensate for legacy stopped-down lenses used on dumb adapters, and gave you focus peaking to assist in manual focus. In addition to what was available via the E-mount camera, on the A99, legacy lenses could be used at their original field of view and could also benefit from IBIS.

Fairly soon after the release of the A99, Sony were selling off reconditioned A99s in the UK at over £1000 under RRP. It was the incentive I needed. I ordered one. I reasoned that I might even remove the SLT mirror and use the A99 as a manual focus camera. Then one of my Dutch friends expressed an interest. I ordered one for him too.

My Sony A99 arrived and looked like it had never been out of the box. It had a ‘reconditioned’ sticker on the base, but the first picture I took with it was numbered ‘0001’. When the other camera arrived, I checked that over and at my friend’s request, took a test shot. Another ‘0001’. It was notable that the second camera’s serial number was just one higher than the camera I had ordered for myself.

Now, whether there was just an ‘iffy’ batch which had been brought back up to spec before being sold as refurbished, or whether these cameras were among those available to people at launch events and were simply never used, I can’t tell. The Shutter on the A99 is rated for 200,000 actuations, but mine must have done well over twice that in the 12 years I’ve been using it (8 of those very intensively). In my experience, reconditioned is worth the risk.

I never did remove the mirror. The AF was good enough to win me over, and the sensor noise never led to me resenting the loss of light to the AF sensors. My worries about the robustness of the pelical mirror led me to research a replacement part, but I never pulled the trigger on it, and it has never been a problem.

In the end, dust wasn’t a huge problem either. Any that gets onto the beam splitter is way out of focus. Although there is no sealing around the beam splitter, the extra barrier between the outside world and the sensor, does seem to keep sensor dust down.

I don’t shoot it much these days, but the A99 is a very reliable workhorse. It can go through the wringer and can take a fair amount of hard use.

What happened next – More writing on the wall

In 2013 Sony released the A7, a full-frame E-mount camera (which some people said wasn’t possible due to the size of the mount). The next year they produced a mk II version of the A7, with IBIS (also supposedly impossible due to the size of the mount). Through the late 20-teens, Sony’s A7 line of E-mount cameras gained traction, sales and ‘mk’ numbers. One of the bonuses of the 7’s was that the body depth felt more like an analogue SLR. Due to the small registration distance, they could also use lenses from just about any analogue mount (including ones without mechanical focus rings like Minolta Vectis and Contax G). A-mount was maintained, but did a bit of withering on the vine.

From the start, A-mount lenses could still be used on E-mount cameras: the simplest adapter from Sony was a straight-through tube that allowed the camera to control in-lens focus motors and had a solenoid to stop down the lens at the critical time. There was also another adapter, which used the SLT beam-splitter and a focus motor to power screw-drive lenses.

The third generation of the A7 had multiple card slots and a bigger battery. With the A7R mk IV Sony had perfected their on-sensor phase-detect AF to the extent that they released an adapter that allowed AF with all A mount lenses, regardless of whether they had in-lens motors or not and which didn’t require a pelical mirror.

If the A7 hadn’t caught on, A-mount still had potential to exploit an existing Sony patent.

The Z-shift option (if it ever existed)

Sony had patents for a Z-shift mechanism. It was built on an idea that had been used on the Contax AX analogue SLR, which moved its film plane to AF existing MF lenses (and probably built on ideas from the earlier Mamiya 6). Sony’s version involved a sensor that could be moved back and forward to accommodate different film-to-flange distances and which could possibly be used to Autofocus manual focus lenses. Whether Sony ever seriously considered using those patents (camera companies take out lots of patents, many of which never see the light of day in an actual product), we may never know.

Sony could have used such a system in an A-mount camera, taking advantage of the space in the now redundant mirror-box. This might be part of the reason A-mount lasted as long as it did. A Z-shift camera would have had lots of moving parts and required lots of calibration. It sounds like one of those good ideas that turns into a nightmare. This may explain why it never happened.

In the end the A7 (and derivatives) enhanced Sony’s position in the interchangeable lens market and A-mount was no longer needed, but support for legacy lenses was still given via A to E adapters.

An end to A?

Almost as a last gasp (and maybe a sop to those who had held out with A mount over the years), Sony released an A99 mk II in 2016, which was a de-uglified (but still not pretty) up-sensored update of the A99. Despite a high price, it sold quite well and maintained its price even after the eventual official announcement of the passing of A-Mount. Used prices are healthy.

Sony marked up A-mount lenses as discontinued in 2021. In the end Sony kept A-mount current for 16 years and seems committed to providing maintenance for the remainder of the 5 years after discontinuation (which would make 21 in total). In comparison, Minolta supported A-mount for 20 years (they passed their support commitment on to Sony along with the Camera division). As someone who committed to Konica Minolta’s A-Mount in early 2005, just before KM bailed, I feel Sony have done alright by their customer base.

Because of the LA-EA5 adapter, photographers who got the Minolta 9000 back in 1985 can still use their lenses on modern equipment 40 years on.

Share this post:

Comments

Ibraar Hussain on Sony A99 – a review of the the first mirrorless full-frame EVF camera

Comment posted: 02/06/2025

I read somewhere long ago that Sony not only bought the assets but also the designers and engineers from Konica and Minolta, which means the Sony camera division is made up of predominantly Konica and Minolta pedigree.

Abandoning the A Mount made sense - now we see Nikon and Canon abandoning their SLR mounts.

I used to have an A900 - I sold it as it was too bulky and unwieldy, even compared to a similarly sized Minolta a-9. The Minolta is also a more handome camera than the A900

The A99, I agree, very ugly.

The only SLT camera I had was a low end SLT A55 which was awful in terms of build quality, feel and handling. I shot with the original A7 which I was on the verge of buying but was put off by the, comparing to the A900 and A700 (and KM 7D) the uninspiring build quality, I expected more.

Thanks again

Comment posted: 02/06/2025

Comment posted: 02/06/2025

Graeme Hamilton on Sony A99 – a review of the the first mirrorless full-frame EVF camera

Comment posted: 02/06/2025

Comment posted: 02/06/2025

Tony Warren on Sony A99 – a review of the the first mirrorless full-frame EVF camera

Comment posted: 06/06/2025

Comment posted: 06/06/2025