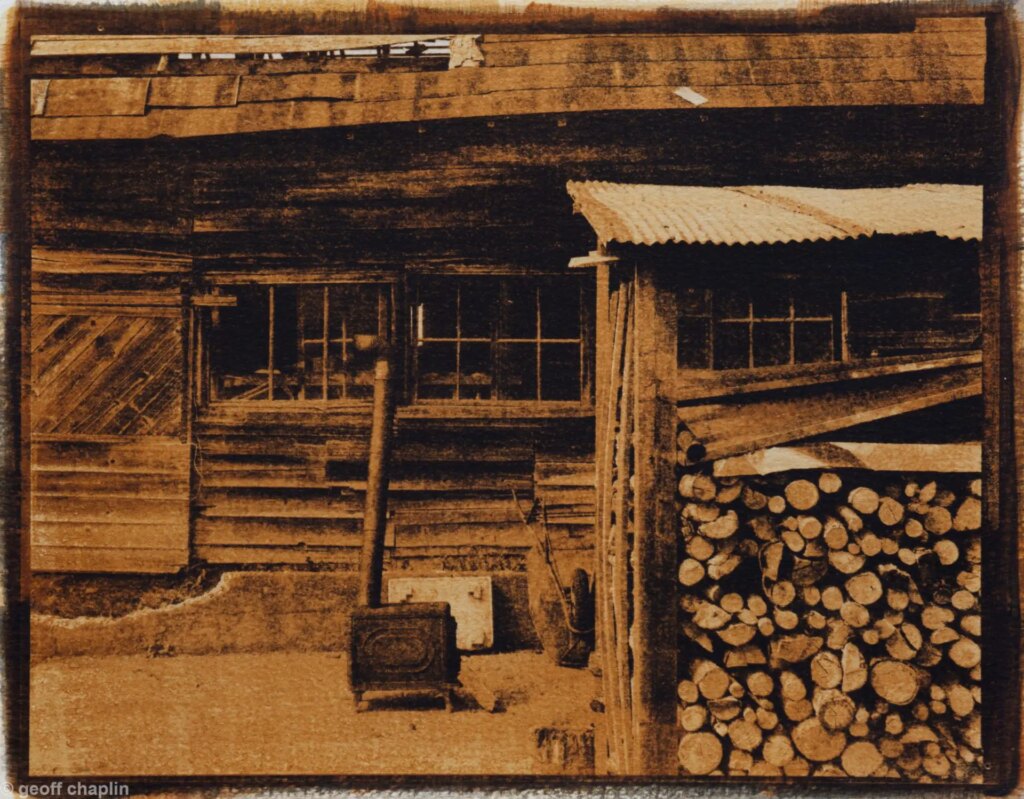

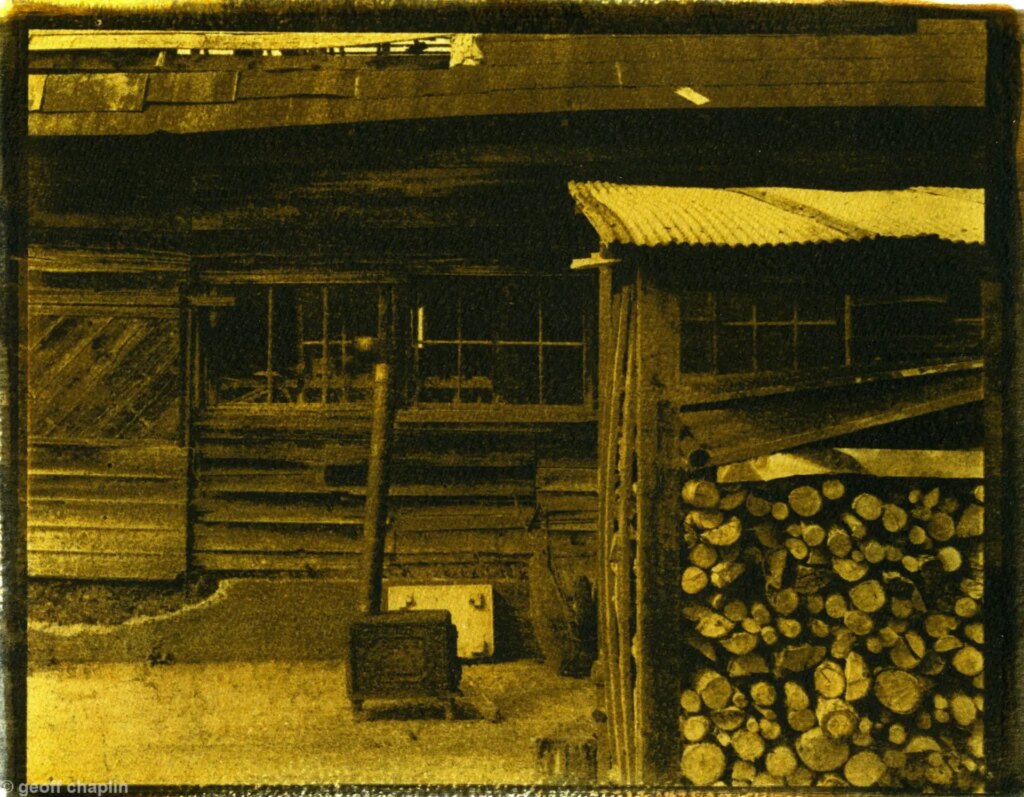

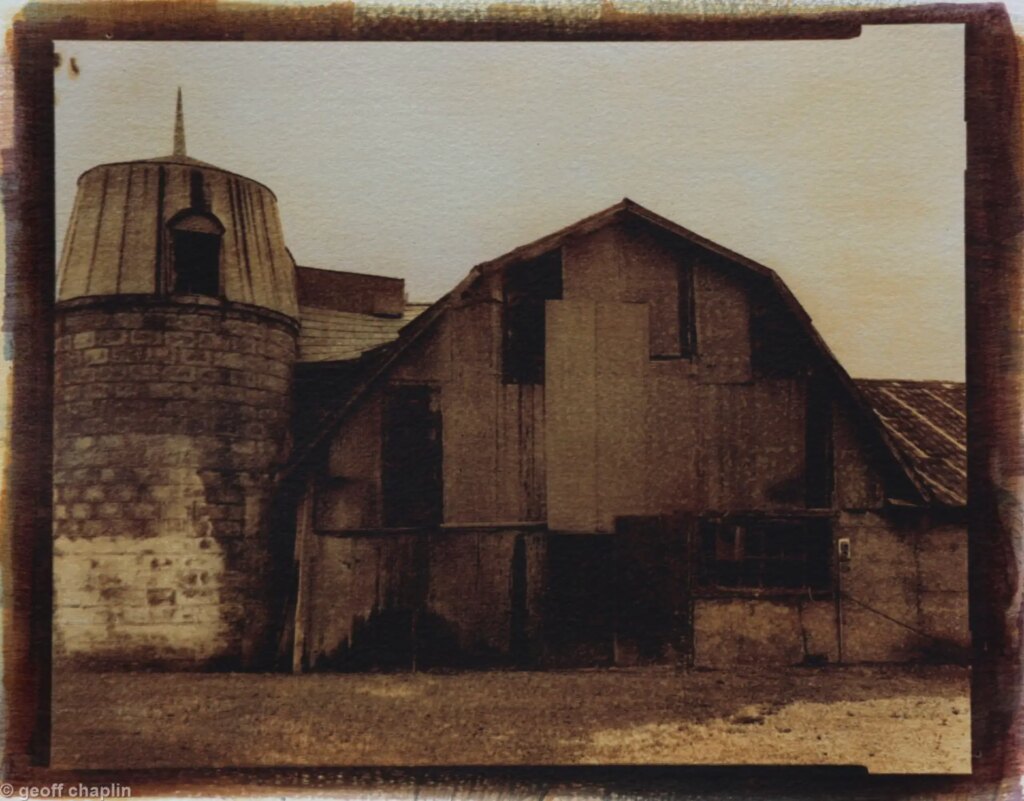

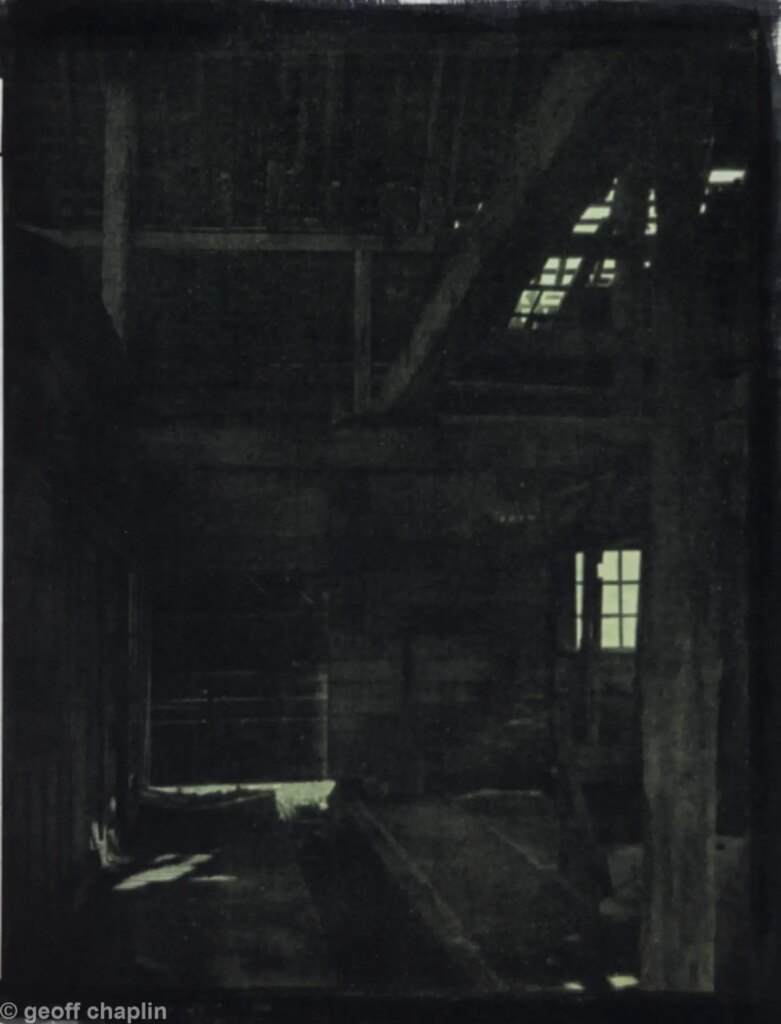

Hokkaido is the northernmost and second largest island in Japan. Just off the Siberian peninsula winters are long, cold and harsh. The main industries are fishing, timber products and farming. With a short growing and cropping season, from May to September vegetable farmers can generally manage just one crop a year instead of three in some areas of the rest of Japan. So many farmers opt instead for livestock farms – primarily cattle (Hokkaido is often termed ‘milkland’) and to a lesser extent pigs. Traditionally farms were family businesses, small with simple equipment and wooden buildings to house and feed a relatively small number of cattle. Over time the successful farmers grew their businesses. And infrastructures, and the others continued until retirement but children took to other professions – often moving to the cities. As a consequence the countryside contains scatted remains of these old small cattle farms, disintegrating silos, milking sheds, grain and equipment stores, rapidly collapsing and becoming scarce now as the weather and large-scale farmers wipe the slate clean.

From around 2005 I started documenting many of these buildings. I had been using a digital camera but after a year I realised I missed the involvement with film, and the entire process itself, and I also hated the way I could just press the print button and get a perfect identically replaceable copy every time. I searched for a different way, something with a life and character of its own, and found “gum printing” (description below). I photographed the barns in B&W using my 8×10 Toyo Field camera. The structures themselves have an aged wooden texture in most cases, and I decided to make prints with mostly brown and black watercolour pigments. The original prints, made on a lightly textured heavy watercolour paper, have a three dimensional quality – the multi-layer printing process together will the colloid I used leads to pigments building physical depth on the paper. Unfortunately its impossible to convey this in the print scans and digitally.

I have shown two versions of the “stove” print; on the “bicycle” print I have used a light blue (which gets obliterated by over-printing on the buildings) to show in the sky. The “ghosts” print is one of three versions. On one version of the original print, a ghost of a man standing to the left of the window can be clearly seen, on another his presence is faint, on the third not there at all. The ghost does not show on scans.

Note on “gum printing”

Like most archaic processes this entails contact printing – nowadays practitioners use digitally enlarged negatives often from digital capture. I mix PVA glue (rather than gum arabic – the traditionally used colloid), the chemical (potassium dichromate – now unobtainable), and artists watercolour paint from tubes to form the emulsion which is then painted on the paper covering an 8×10 area. Once dry the negative is placed on top (face down) and exposed to ultraviolet light. The negative is removed and the print placed in water to develop – about half an hour – then dried. The next day the process is repeated (taking great care to align negative and image exactly) using the same or a different pigment, and so on. I typically make 6 to 12 layers to complete a print, taking up to two weeks. The PVA glue I use is thicker and much stickier than traditional gum arabic making coating difficult but, on the other hand, the print has much greater depth both physically and metaphorically.

Further information on this and other archaic processes can be found at https://www.alternativephotography.com/.

Further images can be seen on my website www.geoffgallery.net.

Share this post:

Comments

Tim Bradshaw on Age or Beauty? – 2: Hokkaido Barns, Glue Prints

Comment posted: 07/05/2023

I think people are slowly forgetting that prints are objects: we all look at images on screens and think we have seen the photograph, but very often we haven't. I find it sad, if inevitable, that so few photographers make prints, or tgink of prints – objects – as the end result of their work.

Comment posted: 07/05/2023

John Feole on Age or Beauty? – 2: Hokkaido Barns, Glue Prints

Comment posted: 07/05/2023

What a fascinating process and subject. I will look for your other articles. We just visited the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke and I can imagine these works would fit right in with the mixed media exhibit. Well done.

Comment posted: 07/05/2023

Alex on Age or Beauty? – 2: Hokkaido Barns, Glue Prints

Comment posted: 07/05/2023

Comment posted: 07/05/2023

JAMES LANGMESSER on Age or Beauty? – 2: Hokkaido Barns, Glue Prints

Comment posted: 07/05/2023

Comment posted: 07/05/2023

Ibraar Hussain on Age or Beauty? – 2: Hokkaido Barns, Glue Prints

Comment posted: 14/05/2023

Here was the original

Fascinating and inspirational and fantastic work Geoff.

I learn something new here every week I think!

Comment posted: 14/05/2023

John Banbury on Age or Beauty? – 2: Hokkaido Barns, Glue Prints

Comment posted: 03/08/2023

Comment posted: 03/08/2023