I’ve long wanted a half-frame 35mm camera. Doubling one’s images per roll is especially great with today’s film costs. I’m an inveterate tinkerer, though, and preferred to convert an inexpensive (but decent) “full-frame” camera, rather than buy a “real” half-frame. But what camera should I tackle? Ideally, it would be:

- Pocketable

- Well-built

- Fully mechanical

- Blessed with a nice lens

- Easily (and reversibly) converted and

- Fun to shoot

Trusting the Universe’s Sense of Humor

For a long time, I trolled the web for candidates. It was difficult to qualify them against my list, and I decided to leave the decision to the universe’s sense of humor. A few months later, my wife and I noticed a “Free” basket leaning against the trunk of an old tree at an estate sale. Inside was the Kodak Flash Bantam camera in the opening photo. It appeared to tick all my boxes:

- Its 2.5×4.5×1.5-inch body is palm-friendly, but weighs in at a sturdy 10oz.

- Fully mechanical, it sports a highly rated 48mm f/4.5 “Anastar” (coated Anastigmat Special) lens, and ranks among the best of Kodak’s long-lived Bantam line. The only model often rated higher above it (and its earlier “Bantam 4.5” sibling) is the beautifully Deco “Bantam Special.” But while that camera commands prices into the hundreds, the Flash Bantam (and Bantam 4.5) can be grabbed online for $10 to $20.

- The camera also seemed simple enough to convert non-destructively and reversibly.

- And in the end, it proved to be extremely fun to use!

Half-framing it would be more than worth the effort too, if my camera performed anywhere near as well as the unaltered unit profiled in this and this article.

Solid and Simple to Use

According to the Kodak Camerosity code on its lens, the camera was assembled in 1951 from metal and Bakelite. It feels solidly built, and is very easy to use. Press a button to the left of the camera’s pop-up viewfinder, and a rectangular lens panel springs forward on sturdy scissor struts:

I also love being able to set apertures (f/4.5-16), shutter speeds (1/200-1/25 plus B and T), and focus distances (down to 2.5 feet) at the lens front. It’s easy to configure the camera before even bringing it to the eye. A highly flexible piece of pocketable kit!

Cleaning the Lens

Overall, the camera was in beautiful cosmetic condition– except for the missing (and unneeded) knobs on its shutter and aperture levers. But bright light through the lens revealed some interior dust and a small smudge. There wasn’t enough of either to do much harm, and the smudge didn’t look like fungus. But I still wanted to clean the glass.

It proved harder than it should have been! The camera’s 4-element/3-group lens contains what I will call four “units.” From the camera front, they are:

- UNIT A: The metal focusing bezel/ring that screws onto UNIT B (and locks onto it with a very tiny set pin).

- UNIT B: The brass focusing-cell that contains the first optical element. (With threads on its outer surface, this unit screws into UNIT C:).

- UNIT C: A brass cylinder (wider than UNIT B) that contains the second optical element. (UNIT B screws into UNIT C… which itself screws into the camera in front of the leaf shutter.)

- UNIT D: A short brass cylinder (painted black) inside the camera that houses two cemented glass elements. It screws onto the back of the lens panel behind the shutter.

UNITS C and D were easy to detach from the camera for cleaning.

However, it proved nearly impossible to separate UNITS B and C for cleaning. Huge effort produced little progress, and it felt like UNIT B’s threads were grinding through sandpaper inside UNIT C. Used judiciously, acetone can be a temporary lubricant. So I pressed an acetone-damped cotton bud into the few visible threads that I’d exposed between the units, and with somewhat less effort, finally got them apart.

Their problem became clear. A previous owner had apparently clamped rough pliers jaws around UNIT B’s outer threads… and deformed them. But I could fix that! TIP: Using a pointed awl like a needle playing a record, I returned the soft brass threads and grooves to as close to their original state as possible.

And then there was UNIT A: the camera’s metal focusing bezel. My last step before loading film would be to “re-collimate” the lens to restore its infinity focus. And we’ll get to that. But past experience with collimation told me that the bezel would need to screw onto and along the focusing cell without any friction.

However, after I removed the single minuscule set-pin that locked the bezel to the focusing cell (and also removed the bezel’s larger infinity-stop screw), the bezel still seemed locked-on. If not fixed, this tightness would move the focusing cell away from any corrected infinity setting.

Long story short, I thoroughly cleaned the threads of all four UNITS with acetone (being careful to keep it away from the lens’s “Lumenized” coatings)… and then cleaned all glass surfaces with cotton buds and Kodak lens solution. (The internal smudge I’d seen before looked like finger grease, and came off easily.)

Re-assembling everything and again looking at bright light through the lens, it was now pristinely clear. And the lens worked smoothly

Masking the Film Gate

Next, I masked the camera’s film gate– at the rear of the bellows– for half-frame photos. The Flash Bantam was designed to throw 39x28mm images onto 828 roll film (images nearly one-third larger in area than 35mm’s 36x24mm). So while 35mm “half-frame” photos are around 18x24mm in size, Flash Bantam half-frames would be more like 20x28mm.

Collimating the Lens

After all of the above, I doubtlessly needed to “re-collimate” the lens to restore infinity focus. Though it sounds complicated, the process can be fairly simple. I’ve used SLRs to collimate several vintage rangefinder lenses. But this time, I’d use my Fuji X-Pro1 digital to restore the Flash Bantam’s infinity focus.

NOTE: Photographer Mike Elek offers a well-illustrated article about collimation here. Though it involves a different camera, the general description still applies.

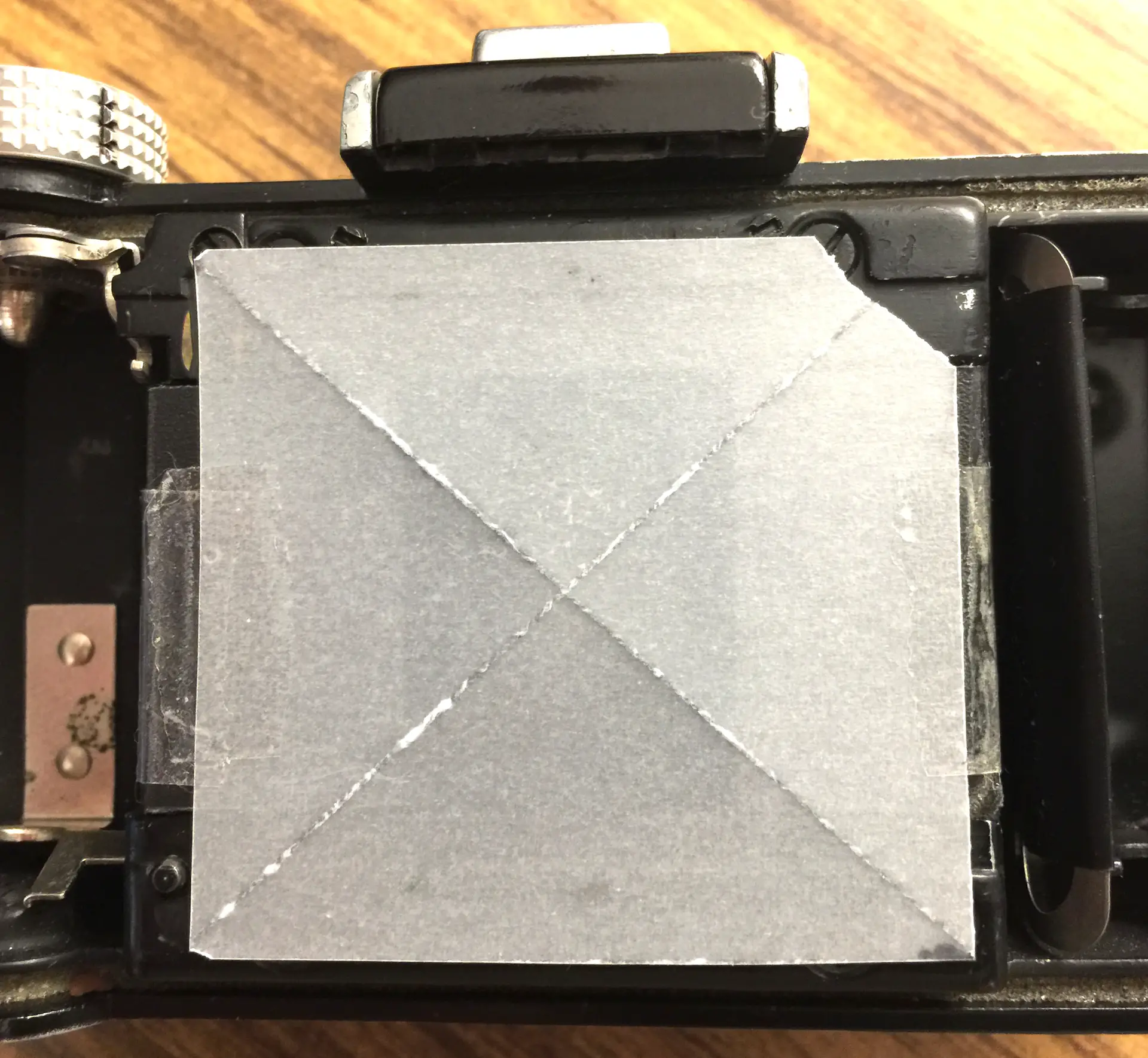

For a collimation-target image, I penned an “X” on a piece of ink-jet vellum and taped it across the film gate:

Here’s the collimation setup (I darkened the room before actually using it):

With the X-Pro1 lens manually focused to infinity, the Bantam’s collimation image would reach maximum sharpness on the Fuji LCD when I turned the Bantam’s focusing cell to its own infinity focus. There, light rays projecting out through the Bantam’s lens and into the Fuji’s would be parallel and the image projected on the Fuji sensor would become sharp– as if the Bantam was actually located at infinity. (And with both lenses focused to infinity, the distance between the cameras wasn’t critical.)

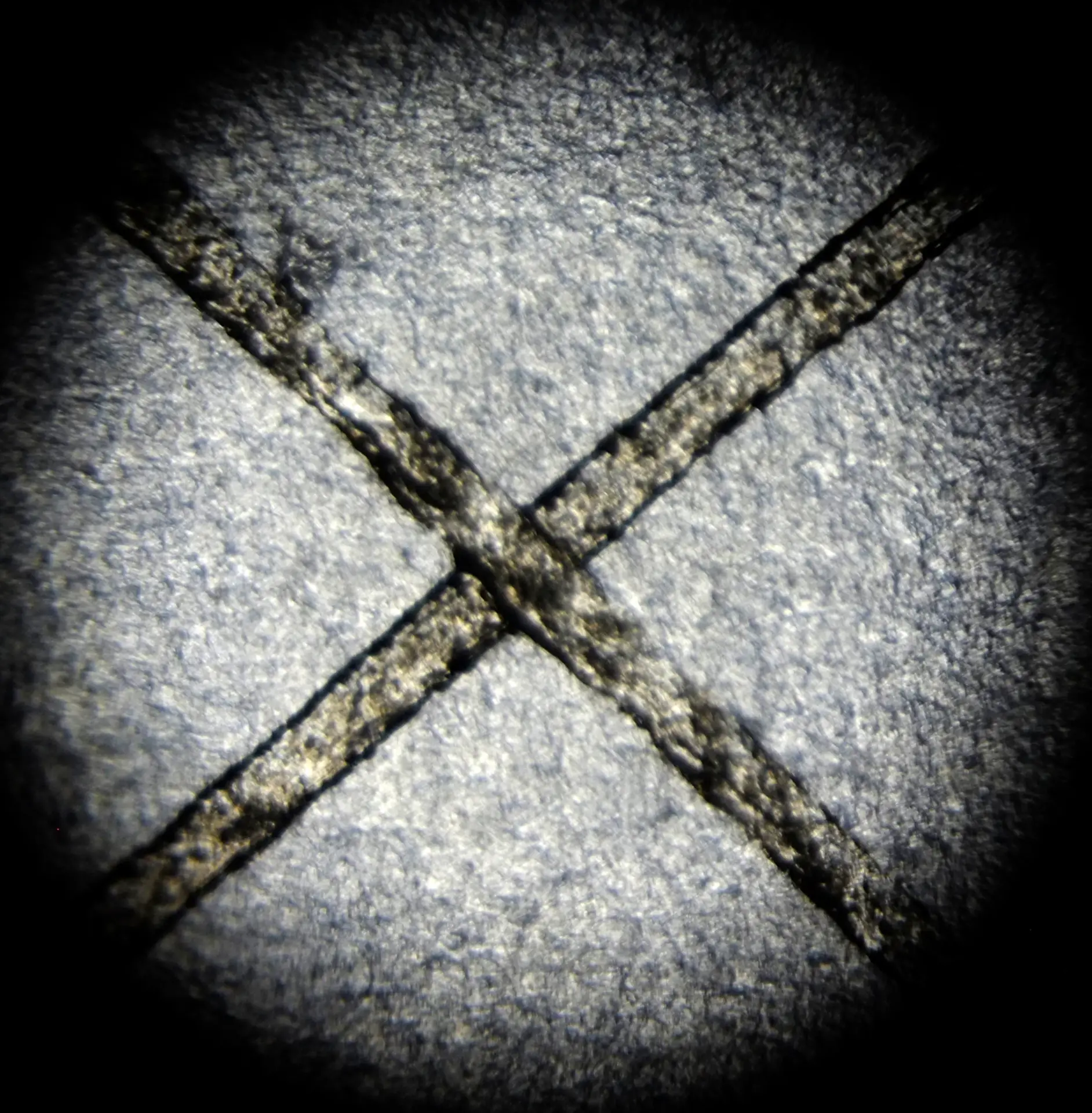

The first collimation image didn’t wow me:

But after a few small adjustments of the Bantam’s focusing cell, it sharpened significantly:

And now came the potentially touchy part I mentioned earlier: moving the metal bezel on the focusing cell without also rotating the cell out of its new infinity focus. Pressing the blade of a rubber spatula firmly against the side of the focusing cell to help hold it still, I gently turned the bezel until it almost touched the camera faceplate and the bezel’s INFinity mark lined up with the faceplate’s focusing diamond (as shown here):

A last quick collimation check showed that infinity focus hadn’t changed.

That’s probably enough for now! In Part 2, I’ll describe my:

- Half-frame winding strategy

- Fairly simple film-loading procedure and

- Shooting techniques

And then, Part 3 will describe my first attempts at Caffenol development (with hopefully at least one sharable image)!

–Dave Powell is a Westford, Mass., writer and avid amateur photographer.

Share this post:

Comments

Ralph Turner on That time I “Half-Framed” a cute Kodak Flash Bantam camera (Part 1 of 3)

Comment posted: 14/02/2023

Comment posted: 14/02/2023

Kurt Ingham on That time I “Half-Framed” a cute Kodak Flash Bantam camera (Part 1 of 3)

Comment posted: 14/02/2023

Comment posted: 14/02/2023

Hamish Gill on That time I “Half-Framed” a cute Kodak Flash Bantam camera (Part 1 of 3)

Comment posted: 14/02/2023

Comment posted: 14/02/2023

Dan Emerson on That time I “Half-Framed” a cute Kodak Flash Bantam camera (Part 1 of 3)

Comment posted: 14/02/2023

The former, a 35mm rangefinder folder has, in my opinion, the design with most character and a confluence with exposure workflow that maximises the experience. Consequently is my favourite. Interestingly, it has the highest degree of original functionality, that in the series, has a timespan that seems to diminish with the increase complexity of the newness of the coupled with increasing production date.

I am looking forward to hearing of your adventures with caffinol.

Regards,

Daniel

Comment posted: 14/02/2023

Dan Emerson on That time I “Half-Framed” a cute Kodak Flash Bantam camera (Part 1 of 3)

Comment posted: 15/02/2023

The former, a 35mm rangefinder folder has, in my opinion, the design with most character and a confluence with exposure workflow that maximises the experience. Consequently this is my favourite. Interestingly, it has the highest degree of original functionality, that in the series, has a timespan that seems to diminish with the increase complexity of newer models

I am looking forward to hearing of your adventures with caffenol.

Regards,

Daniel

Dave Powell on That time I “Half-Framed” a cute Kodak Flash Bantam camera (Part 1 of 3)

Comment posted: 03/03/2023

I just noticed that you re-posted your comment, so I'll see if I can delete the first version. And if I can, I'll repeat my reply here! Since acetone is very penetrating, it may take a series of minute applications to get it under that focus ring without also reaching glass elements. Since the ring is stuck, it seems worth trying. And as much as is practical, use just sightly damp cotton buds, and hold the camera at angles that prevent the acetone from flowing inside too rapidly!

Robert on That time I “Half-Framed” a cute Kodak Flash Bantam camera (Part 1 of 3)

Comment posted: 12/08/2023

Wonderful idea and article regarding the process. I was wondering if you could share any images of the lens disassembly, I am having a little bit of difficulty following it. I'm interested because I was wanting to clean the lens on my Bantam Flash.

Again, wonderful article! cleaning

Robert

Comment posted: 12/08/2023