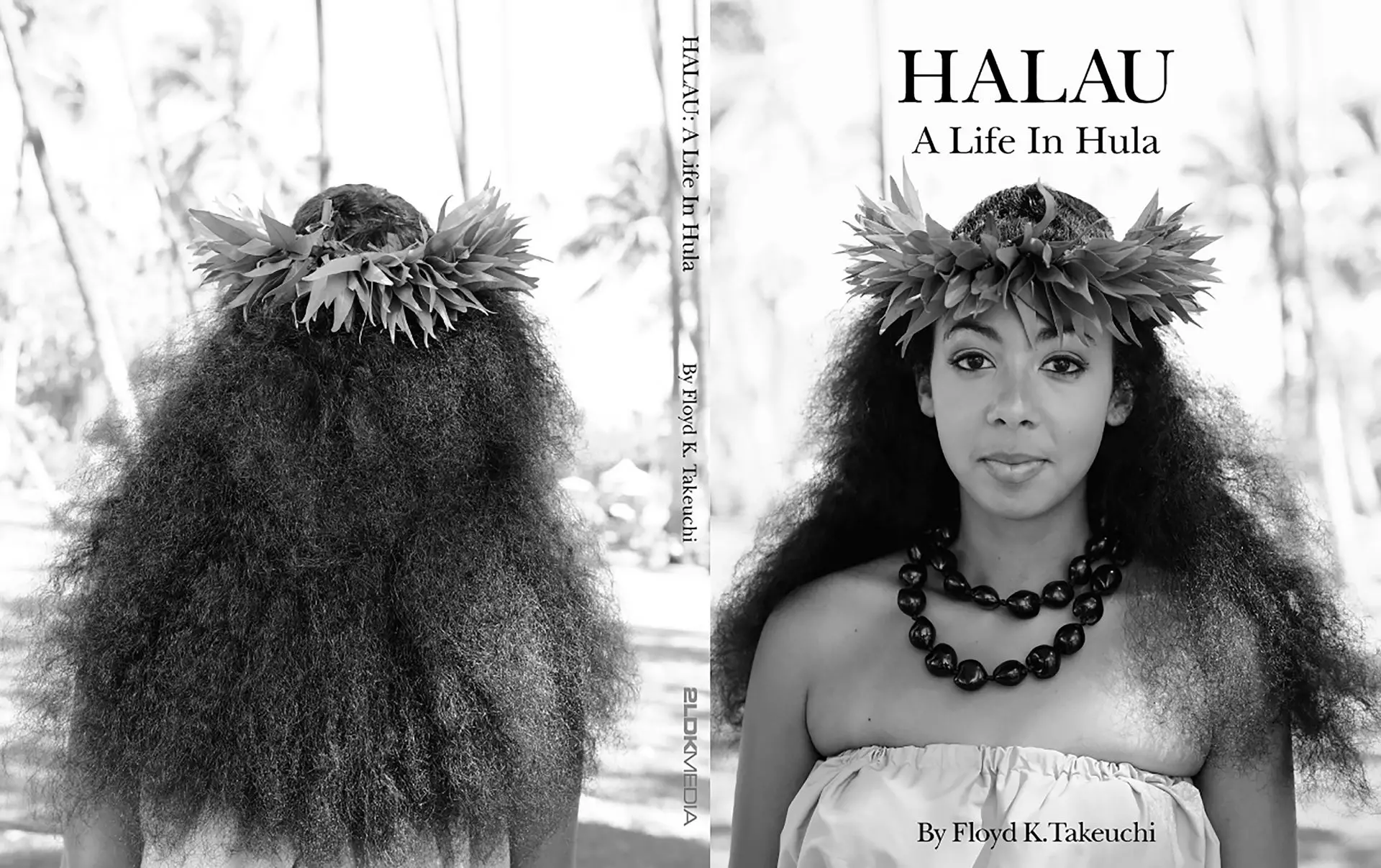

The cover image above was shot with the idea of using it for the cover, thus the photograph of the back of the dancer’s head.

I thought I knew a thing or two about publishing a zine. In a previous life, I ran a Honolulu, Hawaii-based media company that published six monthly consumer magazines. We covered the market – among our titles was a regional city magazine whose beginning could be traced to the days of the Hawaiian Monarchy in the 19th Century; a regional business monthly, one of the oldest titles of its kind in the western United States; and a monthly that covered politics and business in the vast reaches of Oceania. I was also, at various times, editor and publisher of the business and Oceania publications.

I mention this diversion down memory lane only to make a point about publishing a zine – the small run, magazine format publication that many photographers have taken to in the digital era. Here’s the thing. I thought I knew something about publishing a magazine. And I did, as long as you have writers, graphic designers and photographers all producing for you. Do everything yourself, and legacy publishing experience is about as useful as bringing a Watson bulk film loader to a launch party for the latest mirrorless digital whiz-bang camera body. In short, in the world of self-publishing zines, you’re only as good as your last zine. I’ve self-published seven zines through Blurb.com.

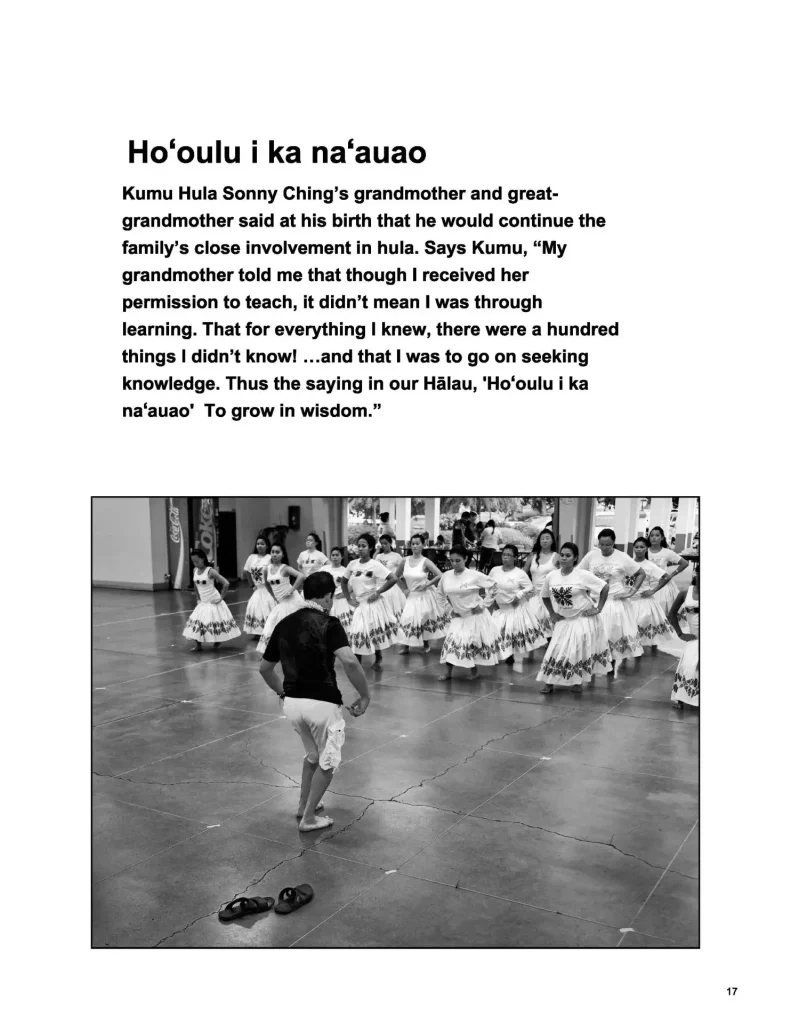

This point was driven home to me when I finally finished editing my biggest zine yet – 116 pages, nearly all photographs made in 2010 and 2011. It was a project that I’d wanted to shoot for years – a behind the scenes look at what it takes for a top-tier hula school to produce the stunning beauty we see on hula mounds or on television and movies if you aren’t lucky enough to live in Hawaii.

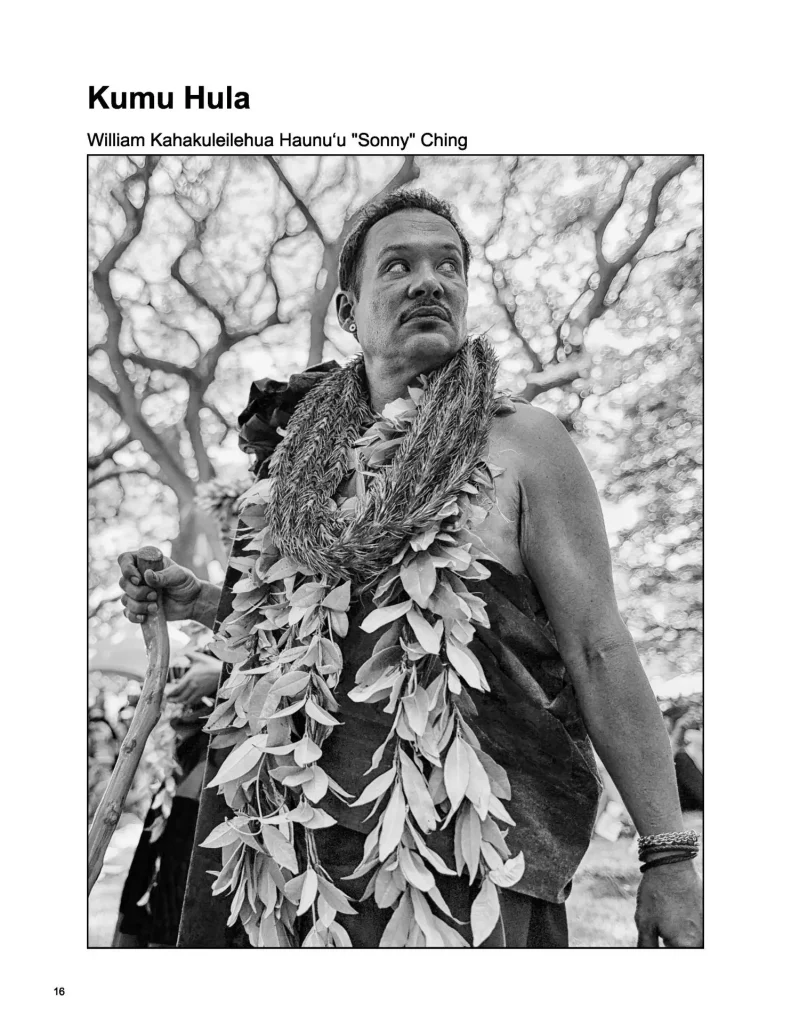

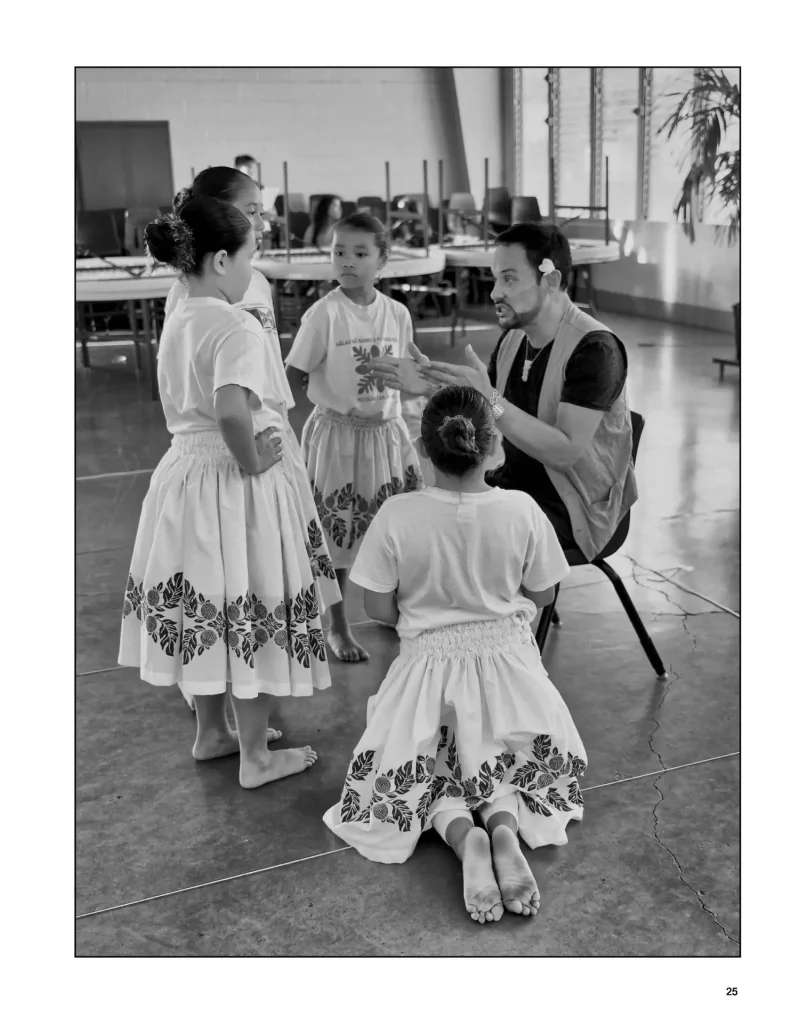

Thanks to a relative, I got an invitation to meet with one of Hawaii’s most honored and successful kumu hula (a teacher of hula), Sonny Ching. He is Kumu Hula of Halau Na Mamo O Pu’uanahulu. I told him what I wanted to do, essentially share through my photographs what his halau (or school) does to prepare its students to dance with beauty and grace grounded in the values of the Hawaiian race.

Most kumu hula are understandably protective of their teaching methods. They’re often passed down from generation to generation, a hula family’s most carefully guarded secret. So when Kumu Sonny said I could photograph his practice sessions, I asked, “What should I not photograph?” He had earlier told me he was honored that a professional of my caliber would be interested in his halau. Kumu Sonny looked at me and said, “You can photograph anything you’d like.”

Thus began a two-year project that had me shooting three to four nights a week, all year round. Like many successful halau in Hawaii, Halau Na Mamo O Pu’uanahulu has sister halau in Japan, which is a hula crazed nation. I paid my own way to Tokyo to join Kumu Sonny and some of his top teachers and dancers work with their Japanese dancers to put on a public concert. At the end of the two years, I had thousands upon thousands of digital capture images.

I was ready to turn the images into a book. But life has a way of upsetting even best laid plans. Just as I was about to begin the editing, turning thousands of images into about 100, my elderly parents began their decline. The period 2012 to 2019 turned out to be a time of hospitalizations, health care crises, and finally the passing of my father in 2016 and my mother in 2019.

The result was finally a period of calm, and the need to finish up projects with loose ends. I dove back into a mass of digital files, thousands upon thousands of photos, that had waited patiently for me. I had the original NEF RAW files produced by the camera I used for the project, a Nikon D700. But I also had initial selects from each day of shooting, all converted into monochrome images.

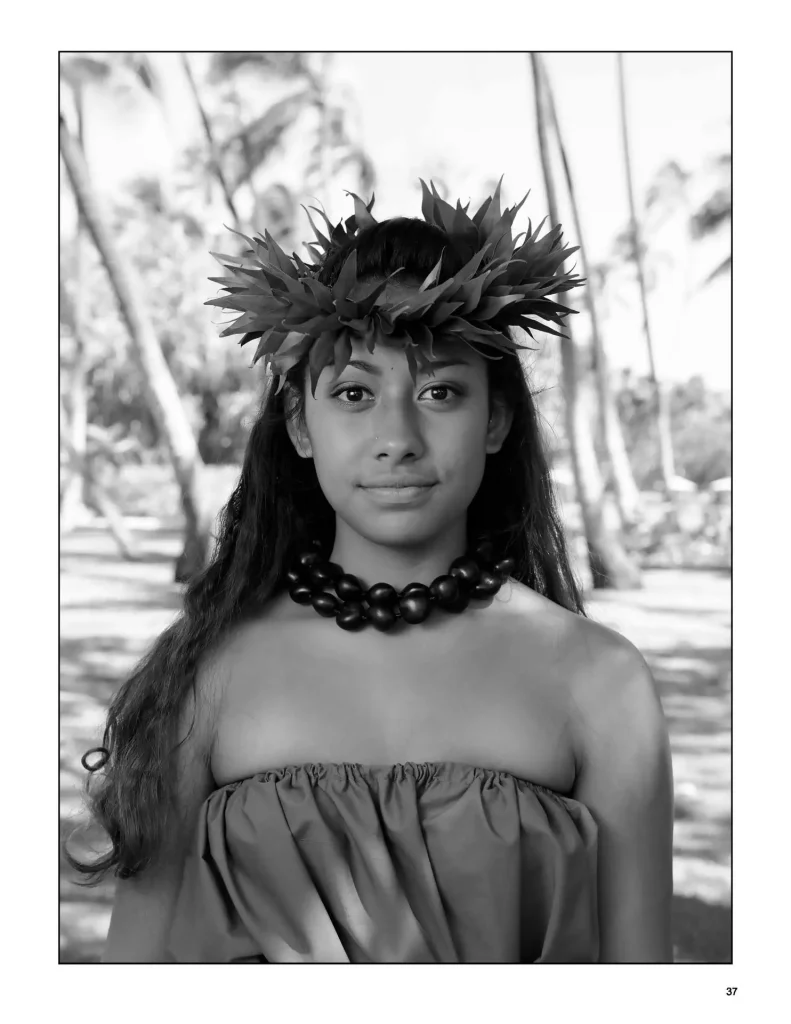

It soon became clear to me that I could spend another decade working the files. I remembered the journalism adage, “Go with what you’ve got.” And that’s exactly what I did. Over a period of about three weeks, I went through folder after folder, picked selects, and from that group, selected the relative handful for each category that I’d set up: the kumu, students (teens and older), young students; students in Japan; and public performances. I had chosen to make this a black and white project, but kept the public performance photos in color.

So what did I learn? First, should you be hankering to turn a long-term project into a zine, I urge you to be fastidious about how you identify subjects, placaes, dates, etc. I got sloppy, in part because I got so busy with the project. Big mistake years later.

Second, spend a lot of time thinking about how you parse the photos to a workable number, and then how you sequence them to tell your story. I was fortunate in that I’d had before this project nearly 40 years in journalism, either as an editor or reporter, and later an editor and publisher of consumer magazines. I had a sense of what’s required by aggressive sequencing. If you don’t have similar experience, I suggest turning to YouTube and the contributions by Dan Milnor. He’s a photojournalist by experience, but is now a self-described Blurb evangelist. His videos, particularly about sequencing, is necessary and bracing tough love.

Three, take you time playing with possible layouts, etc. I only know Blurb, so forgive me for focusing on its platform. Blurb offers a free layout program called Bookwright for those of us who don’t know any of the layout programs.

Bookwright accepts jpgs. Four, be sure your photo files are sized big enough with resoluion to spare. I size my files at 300 dpi. Single images are sized to fill a full page in the zine (8.5 inches x 11 inches). If I have an image that might be a spread (tough with the zine’s spine guaranteed to cause problems with nearly any image).

One other note for first-timers: your zine may be the exception, but be realistic about your publishing goals. The truth is you are likely to sell a few zines online (Blurb has its own online bookstore), and perhaps a few more if you hustle and sell them to independent bookstores, camera shops and the like. But retire early on the profit selling zines? Not likely.

That said, a quality zine is a joy to behold. It’s your work, and zines are cheaper to produce than ordering a single, large custom print. I use them for either personal projects or as an impactful portfolio when I’m seeking commissioned work.

I noted early on that you’re only as good as your last zine. Would I do another as big as my hula zine? You bet, and I’ve already started planning how to be better organized to make process faster.

Halau: A Life In Hula is available at the Blurb online bookstore: https://www.blurb.com/b/10619440-halau

Share this post:

Comments

No comments found