The Olympus OM707 (OM77 in North America) is one of a slew of new futuristic autofocus SLRs that burst onto the market in the mid-1980s. It’s a great-looking camera with a big LCD display, built-in autofocus, and control buttons instead of old-style knobs. Like the similar offerings from Minolta, Canon, Nikon, Pentax, and Yashica, it was accompanied with a sleek new range of autofocus lenses.

What’s notable about the OM707 is that its launch in 1986 was a disastrous commercial flop. Along with the only other camera in the range (the OM101/OM88) it was quickly dropped, and Olympus never really recovered as a premium brand.

So what went wrong?

In the eighties, the evolution of manual-focus 35mm SLRs reached its peak, and the Olympus OM-series manual cameras were particularly well regarded for their jewel-like quality.

The Minolta 7000 AF, released in 1985, turned all of that on its head. A few manufacturers had previously dabbled with clunky in-lens autofocus, but here was a new system that completely embraced a new approach. In-body autofocus, LCD displays, control buttons, a new lens mount with a bank of electric contacts, and a new range of lenses with no aperture ring and only a tiny focus ring. Not a control knob in sight, and the buying public loved it.

Other major manufacturers followed Minolta’s lead in the next couple of years, notably with the Canon EOS 650, the Pentax SFX, the Nikon F-501, and the Yashica 230 AF. While the other brands flourished, Olympus and Yashica failed. Neither of them were late to the market, and on paper they both had a lot of the right boxes ticked. Arguably the Yashica didn’t catch on because of its questionable aesthetics. What killed the Olympus was an unfortunate combination of a lot of small design flaws.

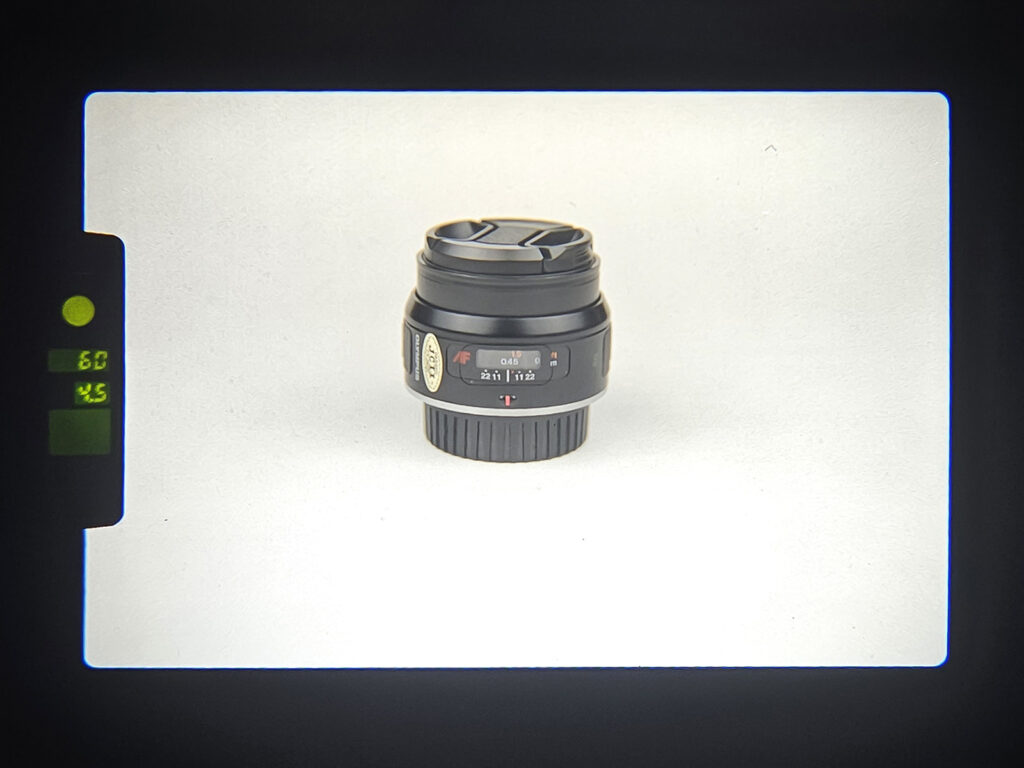

Focusing

Unlike their rivals, Olympus got rid of the focusing ring completely and their AF lenses had no external controls other than for zooming. Thankfully autofocus works reasonably well, has a focus confirmation light in the viewfinder, and locks with a half-press of the shutter release. The alternative is to switch to ‘power focus’ mode, and manually control the AF motor using a left-right slide switch on the back of the camera. It’s rather clunky, and doesn’t even provide focus confirmation. When using autofocus in dim conditions, the red AF-assist beam is very bright and likely to startle a subject who isn’t expecting it.

Using legacy lenses

The lens mount is physically compatible with the legacy OM mount, although the new system moved the release button from the lens to the body. However when an OM lens is fitted, there are no focusing aids and the only exposure mode available is aperture priority auto, with no indication of the selected shutter speed. In fact, with legacy lenses the viewfinder doesn’t show any information at all. That’s likely to have fallen below the expectations of existing owners of Zuiko glass.

Exposure modes

The only mode available with AF lenses is full program. That’s a step below rivals who offered a variety of automatic and manual control modes. At least the Olympus has program shift (using the same rear slider as power focus) and AE-lock. The viewfinder shows the shutter speed and aperture. If you want to use power focus and program shift together, you’ll have to be quick. Meter, then use the slide to shift to the aperture & shutter speed combination you want, then press the top panel button to switch from AF to PF, and finally use the same slider to focus. Once you’re there, if you leave it more than 30 seconds without a half-press on the shutter, you’ll lose the program shift setting and will have to start again. It’s frustrating.

Ergonomics and build quality

The Olympus OM707 power focus / program shift slide switch is a bit of a pain to use, especially if you’re a left-eye shooter like me. Apart from that the OM707 is comfortable to hold, with a nice big handgrip. Quality issues with the grip contributed to its market failure though. It’s removeable with a quick-release catch, which is a plus if you want to carry a spare because it contains the four AAA size batteries. There’s even a larger version that takes the same batteries and also houses a pop-up flash. The problem is the fragility of the battery door and its catch, which started failing within months when the camera was new. Olympus repaired many under warranty, but the damage to their reputation had already been done.

When I received my Olympus OM707, it took a while to prise the battery door off. It revealed a battery compartment full to the brim with turquoise-coloured battery crud, and the remains of four very old batteries. Of course the door catch was damaged too, and some of the electrical contacts had all but disappeared. After extensive cleaning and some new fabricated parts, I got it working.

Using the Olympus OM707 today

For people who love ’80s nostalgia, the Olympus OM707 is a stylish camera system that’s considerably less expensive than the competition. The simple angular shape is much more appealing than 90s cameras with their (boring) ‘organic’ curves and the obligatory built-in flash squatting on top of the prism. The Olympus body also doesn’t have any of the ‘soft feel’ plastic grips that deteriorate with age. My Minolta 7000 AF may have more technical capability, but it looked a mess when I bought it and I had to replace the split and sticky grips with 3D printed parts.

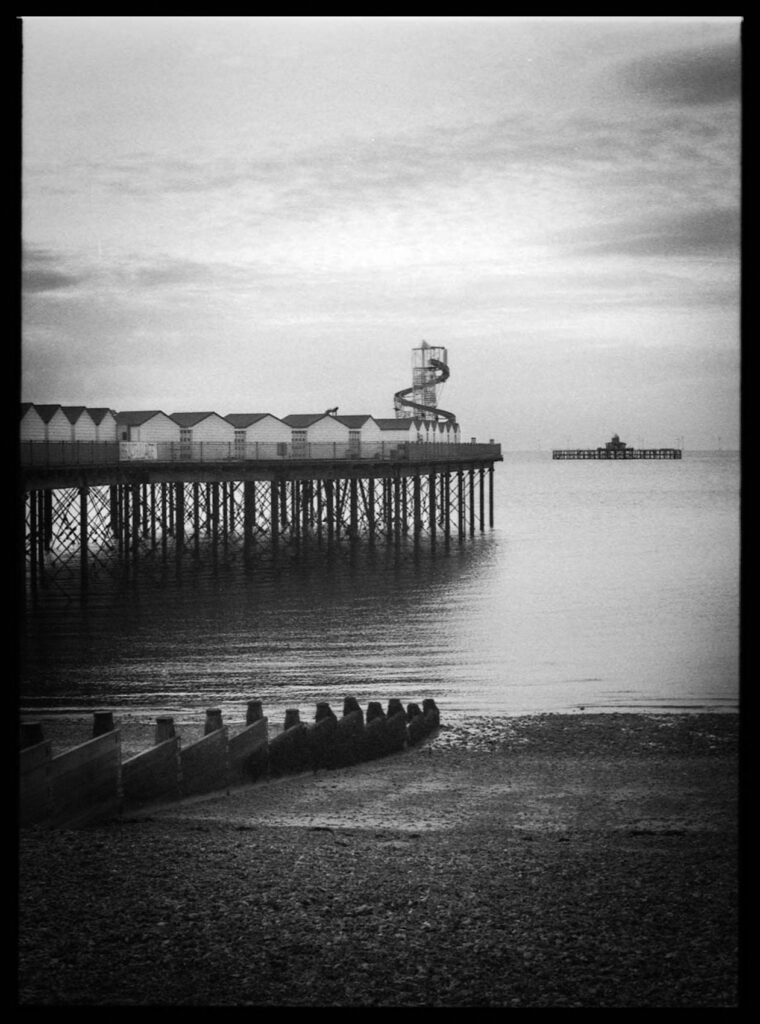

I took the camera and a selection of the AF lenses to a garden open day at Wretham Lodge in Norfolk, and thoroughly enjoyed using it. Here’s some of the photos.

Share this post:

Comments

Andrew Thompson on Olympus OM707 – The Autofocus Underdog

Comment posted: 23/06/2025

Never heard of this Olympus (same for the IS-3000 which was reviewed recently). I ended buying one of those and the first roll through it was encouraging.

I know my next step will be seeing what’s out there. I don’t need one, but…

Thank you Stuart.

Comment posted: 23/06/2025

Gary Smith on Olympus OM707 – The Autofocus Underdog

Comment posted: 23/06/2025

Thanks for posting!

Comment posted: 23/06/2025

Joel Keller on Olympus OM707 – The Autofocus Underdog

Comment posted: 24/06/2025

Wish it had aperture priority and I think the ISO setting was a bit off even though it could read DX codes, but I was surprised at how intuitive it was.

Some shots are here: https://www.instagram.com/p/C6zQzzgv1zw/?igsh=dGU3OGJvNHR2M2Jj

Comment posted: 24/06/2025

Comment posted: 24/06/2025

Jeffery Luhn on Olympus OM707 – The Autofocus Underdog

Comment posted: 25/06/2025

Thanks for an interesting posting. Olympus was a very forward thinking company. The XA stands out as a particular example of creative thinking.

Comment posted: 25/06/2025