Telephoto lenses create such a literal and metaphorical distance between the photographer and their environment. Although one of my favourite lenses to work with is a 90mm, I really value a close proximity workflow even when using that narrower field of view. 21mm is a 90 degree field of view, a perfect right angle, and has recent become an extremely valuable contribution to the stories I am currently telling. The word “immersive” comes to mind.

I first used 21mm many years ago on the Leica M mount, a Zeiss 21mm f/2.8 Biogon, although my application was to architectural interiors, fashion portraiture, and other ephemeral pursuits. I used it with an external viewfinder, but struggled to figure out a consistent method I was happy with.

I have used a borrowed 20mm Nikon lens on SLR, and found it much simpler without the external VF aspect slowing me down. Manually focusing while framing is intuitive where doing one task per VF just doesn’t work for me. This makes rangefinders a difficult recommendation for this approach, unless you’re able to find a way to make it work for you. I have looked through, but not yet photographed with, a Nikon 18mm, which feels roughly the same although I know there’s a difference.

For the sake of this article, I want to talk not specifically about my lens in particular, but generally about the philosophy and approach that comes into play when using that range of very-wide-but-not-fisheye lenses, 18mm to 24mm, while photographing a humanist, narrative based, photography project. Any wider (15mm and below) and you start to arrive at the limits of the kind of optics I want to be using to photograph people and document reality. Any longer and you start to reach the more classic all-purpose wides, 28mm and 35mm – which enough has already been written about, and then some!

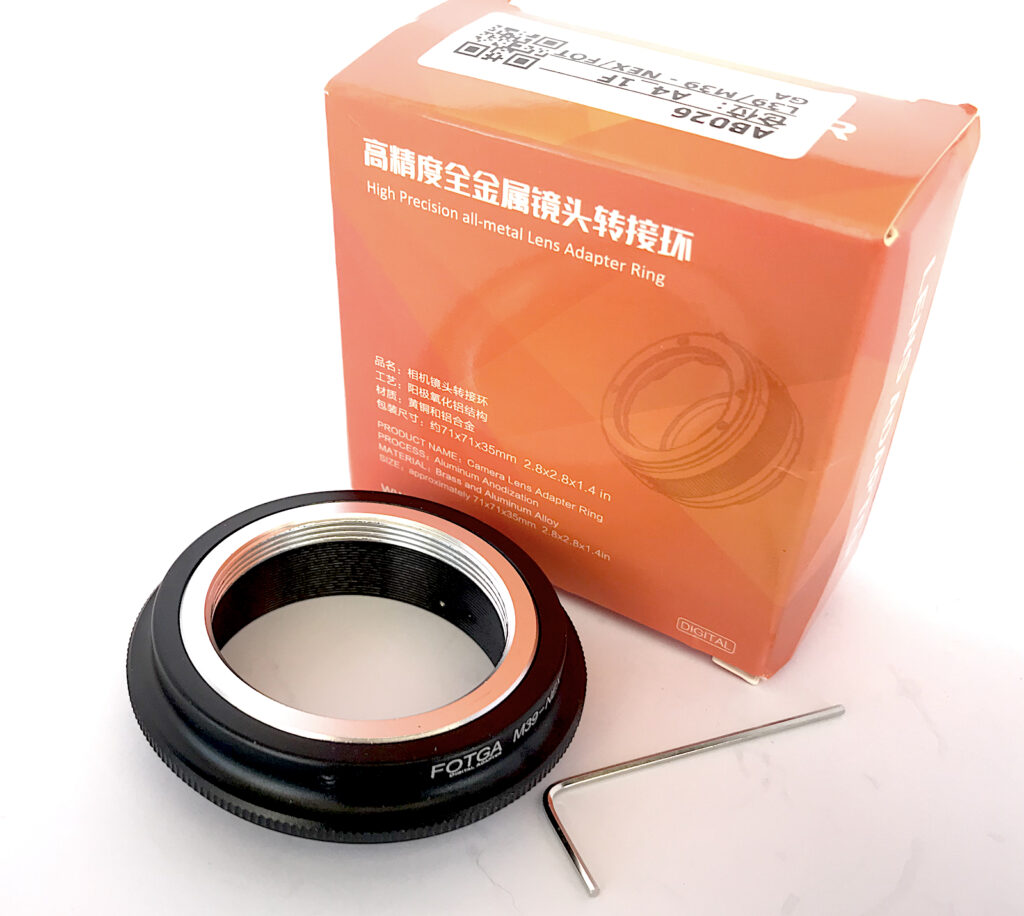

The lens I am currently using is the Contax G mount Zeiss 21mm f/2.8. As I mentioned before, the secondary framing viewfinder really threw me off on my Leica, and in theory it ought to do the same here. However, because I am able to rely on the autofocus system I don’t often need to switch between viewfinders in the same way it was essential to do so on M while critically focusing. I can keep the framing VF to my eye, and listen to the sound the autofocus makes, which lets me know whether it has locked on or not.

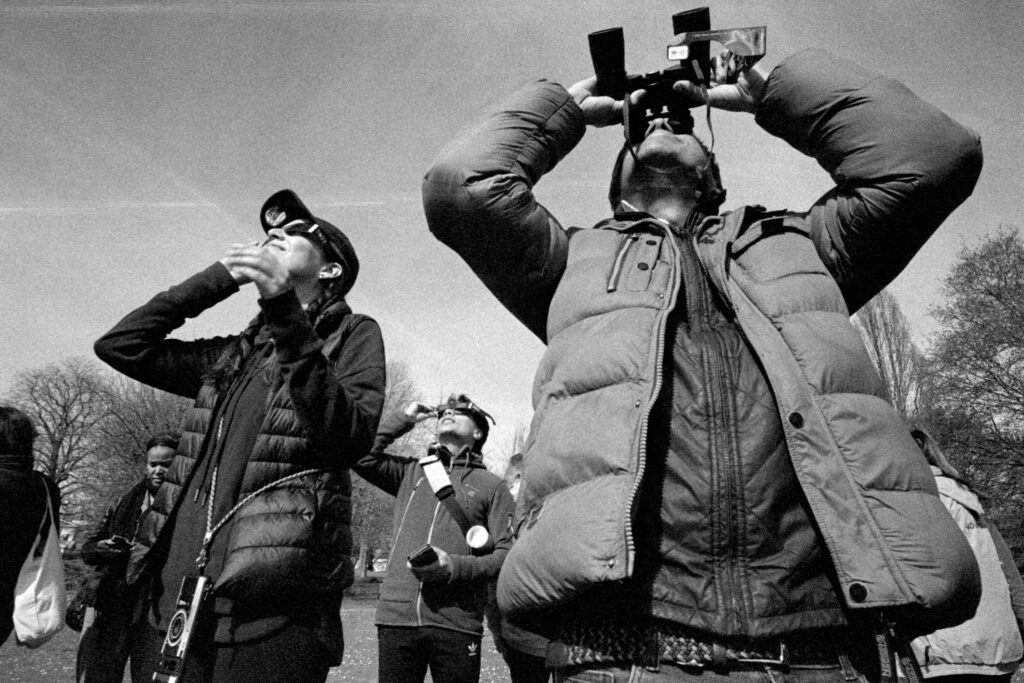

With glasses neither the on camera finder nor the external one is perfect, but a rangefinder is an approximation anyway – and on top of that I can guess the framing by simply knowing that it’s including everything within that 90 degree angle of view from the lens. I don’t want this to be a review of any lens in particular but an application of use to certain scenarios. This is a lens I can manoeuvre without looking and framing and get usable images – at times dropping the camera down to my knees for a low angle quickly in a crowd, or holding the camera over my head and knowing that I will manage to catch at least some of the action unfolding in front of me.

You have to position yourself close, sometimes only centimeters from your foreground. You have to be more than comfortable in a tight space, at the front of a crowd, or caught up in a scuffle. My general working conditions with this lens are within a “bubble” of a few meters. For a well composed image I like to be aware of everything around me in a two meter radius.

If you are a street photographer you have to be very friendly. If you are a documentary photographer you have to be trusted. These are levels of closeness that you have to be welcome in in order to really do the work you need to do. If you aren’t welcome, or feeling unfriendly that day, you may be better off with a 200mm and some distance. The images will suffer as a result in my opinion, compared to what’s possible from embracing a friendly, close approach. This is not a sidelines lens. You have to be inside the scene; among the participants of whatever situation you are documenting.

My reason for picking this focal length up again when I did was because I was photographing in a space with a 28mm lens and could not include everything I wanted to in the frame. I wasn’t able to step backward and compose with distance due to the cramped conditions and crowd around me. It’s a repeatable situation, so when I go again with this lens I will know if I need to go wider, or whether this is exactly what I need (hopefully the latter, from my use of it so far!).

When using this lens indoors, I sometimes use flash, which takes extra care as the one I have doesn’t have a very wide coverage. This means there is a vignette effect on those images, with extra dark corners. Some flashes have coverage for wide angle lenses, so if you can find one of these you may have a better result. Otherwise, work with that aesthetic, which isn’t the absolute worst.

Flash use also means losing the VF, as the hotshoe is occupied. Unless you’re using a cable setup, which I don’t, this means you’ll be shooting blind – all my flash images are shot without the ability to compose using the correct equipment, instead I have to approximate and anticipate where the edges of my frame will actually end up.

The minimum focusing distance on my lens is 0.5m, on an SLR there may possibly be ones which go lower. However, even much lower still won’t give you the same kind of framing you can achieve for portraits with a 50mm, or even a 35mm. You’ll be including a lot of background and context, so for one-subject portraits you’ll have to make sure everything is working to your advantage rather than existing as dead space. Environmental portraiture is fantastic for documentary work, so I’m happy to work with that extra space, and take on the challenges that come with it.

Practicing wide angle compositions will be incredibly valuable when working quickly in rapidly changing environments. As I said, you will be very close to people, so learn to incorporate their layers as foreground, transitioning to midground and falling without conflict against a background – everything in your frame in harmony, working in service of your subject and scene, not a cluttered mess, which is easy when taking a snapshot approach.

Working within chaos means being able to quickly adapt your composition and accepting unexpected elements. A hand drifting into your frame becomes a grounding foreground element, people stepping in and out on the edges becomes a vignette to bring attention to the centre of your frame. This is not a lens for perfection all the time – it’s scrappy, and requires a degree of open mindedness to really become comfortable with what it can do.

The above video shows my approach using mostly my 21mm (with a few 45mm frames towards the end) in chaotic, close quarters situations at the 825th Atherstone Shrovetide Ball Game.

The wideness of the frame makes motion blur very manageable – compared with a narrower field of view the distance moved within the frame is much lesser relative to the overall scene. At low shutter speeds, motion blur is not as obvious as it may be with a standard lens. It also means that when panning, the distance you’ll be physically moving will be slower and lesser than with a longer lens, as the moving subject is travelling within less of the frame as you may be used to.

The wideness when metering through the lens can also lead to over-reading parts of the scene that you didn’t actually intend. It’s especially easy to misgauge how much sky is being read, and as a result underexpose the important parts of the scene, which I’ve found to be an issue when working low, pointing the lens upward for that kind of angle – but also sometimes I can overcompensate leading to accidental overexposure. Switching between viewfinders as I do with my Contax kit is unhelpful, and for fast paced scenarios I err on the side of just getting my framing correct and allowing the camera to make its own decisions for metering and focusing. This is my least favorite aspect here, as I really prefer to be the one making the decisions behind my images.

Wide lenses like these are prone to distortion, but this will really depend on the exact optical design of the lens. My G21mm is near perfect, and I’ve often had images made with it mistaken for 28mm and even 35mm results when others ask about them. Do research in advance if considering a lens like this, as there are some really terrible, borderline unusable (to me) wide angle lenses out there in circulation. Most modern designs are very decent, it’s the vintage ones I’ve seen the most issues with, purely based on outdated early lens designs.

Figuring out the limitations of your particular lens when it comes to distortion is essential, and will take trial and error, especially if you aren’t looking through the lens, as with rangefinders. You’ll need to figure out what angle you need to be to you subject – a flat plane will be best for even results, while tilting will start to cause elements to bend away into the edges and corners, stretching them out which I find quite odd to look at. Working close you won’t always be able to kneel or rise to the level of your subject, which means you’ll have to compromise for what is achievable, even when it isn’t optimal.

I’ve found that compositions which are portrait, and from a height, will have an accentuated distorted feeling to them, most likely because of the conflicting perspectives at play. When I am working with the frame horizontal, close up in a crowd, you get a few faces bending away into the corners, but nothing as severe as the visible straight lines and buildings warping and twisting at the edges.

Depth of field will depend on the individual lens, with wide apertures obviously making a difference – but even an f/1.4 21mm lens is never going to have the same falloff as a 50mm. There’s always going to be a lot more in focus than you may be used to from using a standard wide, or mid-focal length lens. Composition is really key for making all the elements in your frame work for you; it can’t be “cheated” by erasing everything in the background by rendering it as lovely bokeh.

Obviously good composition is always a factor with any focal length, but a lens this wide is about exaggeration. A poorly composed image has less to rely on aesthetically without optical trickery or characteristics, as may be present in a standard 50mm, where even at f/4 you can have a neatly compressed, “tidy” frame. My 90mm f/2 is incredibly easy to use with the aperture wide open, as it makes basically everything look lovely, separating it from “reality” in so many ways. You can just highlight a small slice of reality, a clean portrait, or detail. On 21mm, photographing just one thing at a time is very tricky, unless conditions are perfect to allow for it.

The above video shows my approach using mostly 21mm (as well as XPan, you can ignore those in the context of this article!) during the 2025 Vaisakhi Nagar Kirtan procession in Southall.

I find 21mm lends itself well to an “exaggerated” style – visual hyperbole, and proximity means you can emphasise aspects with only slight adjustments – for example a slight shift down to a lower angle will result in your subject looming or towering in the context of the frame, even if the height difference isn’t that much in reality. A small, distant figure as seen by the eye will appear even smaller, even more distant when seen through a wide field of view.

As with any non mainstream gear based decision there is a learning curve to this and similar lenses, especially when working as close to people as I have been. It’s well worth the practice, but I recognise it isn’t for everyone – and that’s OK. However, if the images and ideas I’ve gone over here sound like they may be the right fit, I think it’s well worth attempting to fit an semi-ultra-wide angle such as this one into your line up.

Thank you for reading my thoughts on this kind of lens! The photographs in this article are recent, and I think you can tell that they are still part of a learning process for me to incorporate this approach into my workflow. If you like my images, you might like my YouTube channel, which I’ve been sharing to more frequently, with plenty of wide angle work on show. I buy my film mostly from Analogue Wonderland.

Share this post:

Comments

Ibraar Hussain on The 21mm Focal Length (or Thereabouts) for Documentary Photography

Comment posted: 25/06/2025

One of my two favourite lenses ever! I can't say I've ever used a WA as good as this

Scott Ferguson on The 21mm Focal Length (or Thereabouts) for Documentary Photography

Comment posted: 25/06/2025

Thanks for the thought provoking post, and cool shots. I picked up a 21mm for my M3, a Leitz branded Schneider Super Angulon f4 from 1958, which I think is a brilliant lens and one I use all the time. I have also shot with a 21mm Elmarit from the 90's and for some reason the shots with the Super Angulon tend to come out much better. The more 'modern' lens is perfectly fine, but there's something really nice about the way the vintage lens renders in both color and b&w. It's also much easier to have on hand, as it's tiny for a 21mm and takes 39mm filters, making it compatible with my other Leica glass unlike the Elmarit which has a huge front element and takes a 60mm filter and with the hood on invades the lower third of the frame on the viewfinder. I don't mind the external viewfinder, and the depth of field on the 21mm is so deep I rarely have to worry about critical focus. In daylight with a 400 ISO film, it's a great set up for zone focusing. I tend to use it more for landscape and tricky interiors/architecture where the extra width allows me to get everything into the frame, but have done some street photography with it, and liked the results. However, most often when I'm going out and about in NYC I have a two lens kit with a 1949 50mm Summitar f2 and a Voigtlander Color Skopar 28mm f3.5 -- with those lenses, everything fits nicely into a couple of pockets along with some spare film and a hood for the 50mm. I like shooting street portraits and get in close to my subject(s), and the 50mm is a great lens for that kind of shooting, and the 28mm seems to be the sweet spot for me when things are fast moving and dynamic and I want to be able to zone focus and have a little more 'runway' to keep a moving subject in the frame. But your post makes me think it might be fun to try the 21mm next time I go, which is also small enough to fit in a spare pocket!

Cheers,

s