“You know, I do believe in magic. I was born and raised in a magic time, in a magic town, among magicians. Oh, most everybody else didn’t realize we lived in that web of magic, connected by silver filaments of chance and circumstance. But I knew it all along. When I was twelve years old, the world was my magic lantern, and by its green spirit glow I saw the past, the present and into the future. You probably did too; you just don’t recall it. See, this is my opinion: we all start out knowing magic. We are born with whirlwinds, forest fires, and comets inside us. We are born able to sing to birds and read the clouds and see our destiny in grains of sand. But then we get the magic educated right out of our souls. We get it churched out, spanked out, washed out, and combed out. We get put on the straight and narrow and told to be responsible. Told to act our age. Told to grow up, for God’s sake. And you know why we were told that? Because the people doing the telling were afraid of our wildness and youth, and because the magic we knew made them ashamed and sad of what they’d allowed to wither in themselves.

After you go so far away from it, though, you can’t really get it back. You can have seconds of it. Just seconds of knowing and remembering. When people get weepy at movies, it’s because in that dark theater the golden pool of magic is touched, just briefly. Then they come out into the hard sun of logic and reason again and it dries up, and they’re left feeling a little heartsad and not knowing why. When a song stirs a memory, when motes of dust turning in a shaft of light takes your attention from the world, when you listen to a train passing on a track at night in the distance and wonder where it might be going, you step beyond who you are and where you are. For the briefest of instants, you have stepped into the magic realm.

That’s what I believe.

The truth of life is that every year we get farther away from the essence that is born within us. We get shouldered with burdens, some of them good, some of them not so good. Things happen to us. Loved ones die. People get in wrecks and get crippled. People lose their way, for one reason or another. It’s not hard to do, in this world of crazy mazes. Life itself does its best to take that memory of magic away from us. You don’t know it’s happening until one day you feel you’ve lost something but you’re not sure what it is. It’s like smiling at a pretty girl and she calls you “sir.” It just happens.

These memories of who I was and where I lived are important to me. They make up a large part of who I’m going to be when my journey winds down. I need the memory of magic if I am ever going to conjure magic again. I need to know and remember, and I want to tell you.”

― Boy’s Life

“What would describe it? What word in the English language would speak of youth and hope and freedom and desire, of sweet wanderlust and burning blood? What word describes the brotherhood of buddies, and the feeling that as long as the music plays, you are part of that tough, rambling breed who will inherit the earth?”

― Boy’s Life

While perusing the IPA International Photography Awards Website, with the wealth of fine fine work which is on display I noticed that there seemed to be more Analogue (Film) Photography amongst the many category of Winner than I remember from previous competitions of this sort. Strange but refreshing and I was glad to see specific Analogue categories now present, I may be mistaken (so correct me if I’m wrong) but I was pleasantly surprised (delighted in fact) – sure I use Digital as well, but I’m first and foremost someone who would rather use and would prefer to use a Film camera for a serious project or to make a display of my (somewhat relatively limited) abilities.

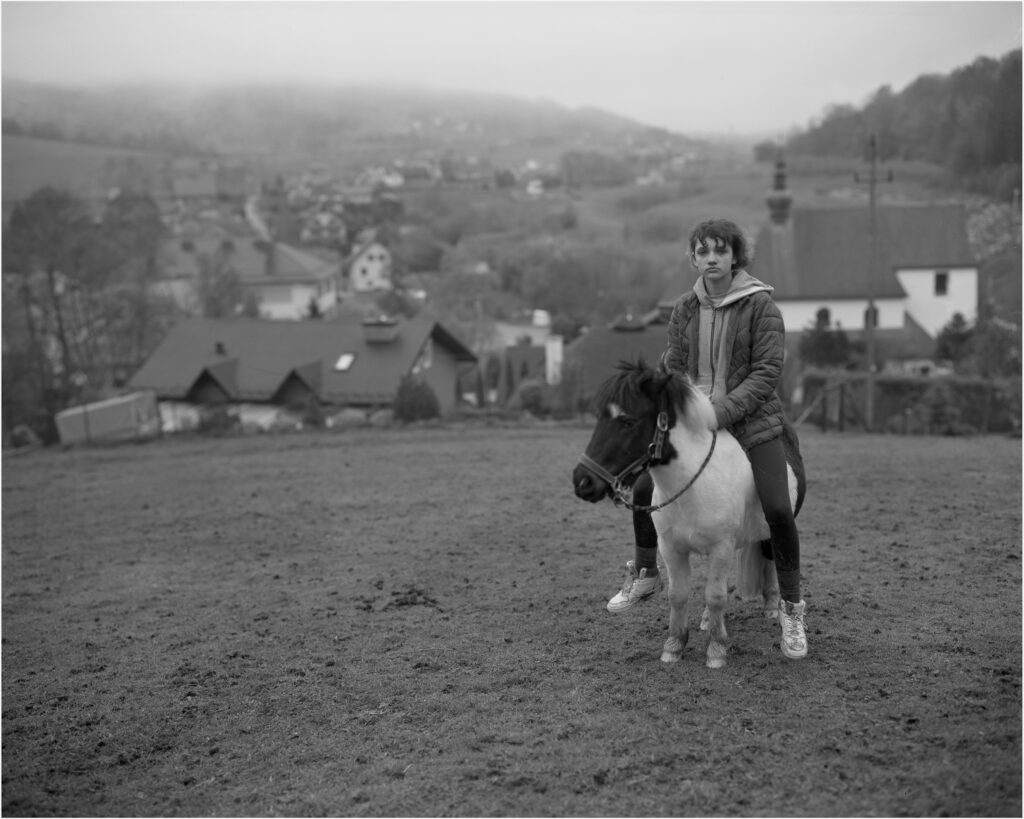

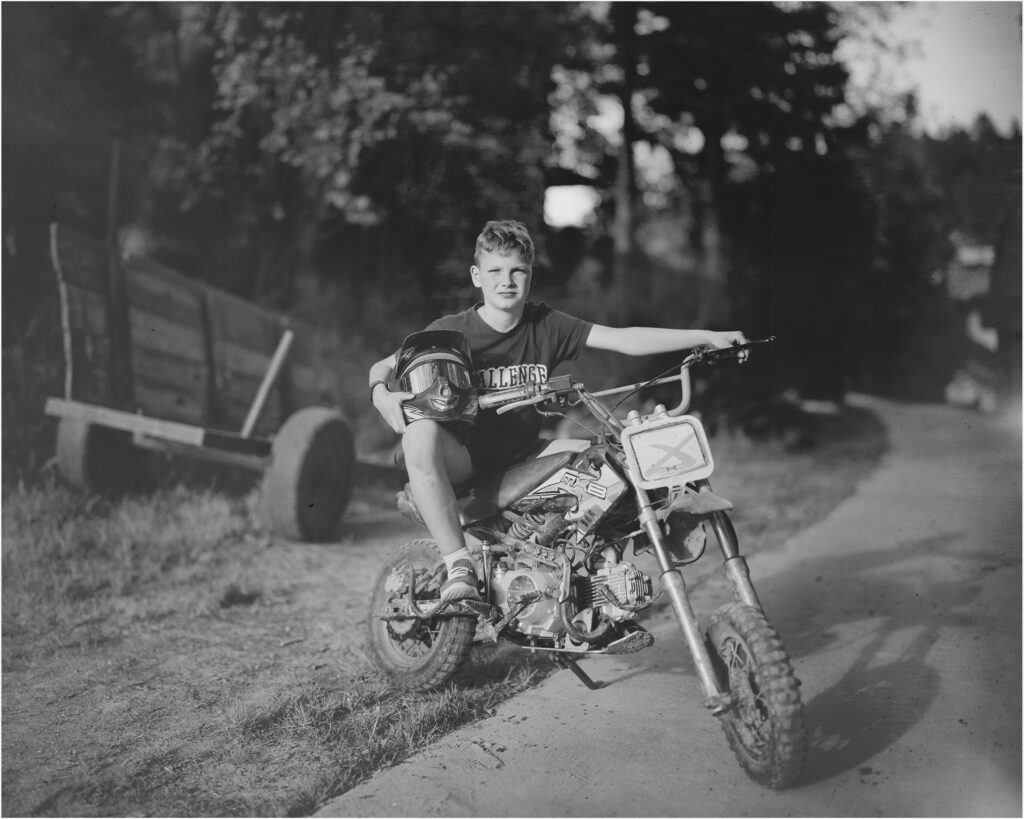

My eye was immediately drawn to a gentle, subtle and almost translucent delicate picture of some boys on motorcycles. The tones were exquisite, the boys faces displayed a feel of innocence combined with the roguish look boys of this age usually possess. The short Spring days of Childhood, fleeting, yet the most solid, most deep and ingrained and memorable days of one’s life – the forge almost, which shapes, moulds and hones the man which one day will come and stay until the Winter end.

Looking further, the series itself is very special. Something draws me to such evocative photography, it stirs something inside and conjures up a mix of happiness and longing, I’m guessing men are all boys deep down inside, all women will forever be girls, and will forever stay as they were before the years and arduous nature of life buried them deep, but the child is always there and at times he appears. Looking at Yehor’s photographs was one such moment.

“They may look grown-up,” she continued, “but it’s a disguise. It’s just the clay of time. Men and women are still children deep in their hearts. They still would like to jump and play, but that heavy clay won’t let them. They’d like to shake off every chain the world’s put on them, take off their watches and neckties and Sunday shoes and return naked to the swimming hole, if just for one day. They’d like to feel free, and know that there’s a momma and daddy at home who’ll take care of things and love them no matter what. Even behind the face of the meanest man in the world is a scared little boy trying to wedge himself into a corner where he can’t be hurt.”

― Boy’s Life

They’re beautiful Large Format prints, with all of the look and feel only an Large Format Photograph could possibly manifest. I had to see more of Yehor’s work and after a simple Brave Search I was able to enjoy Yehor’s artwork on canvas and on silver halide.

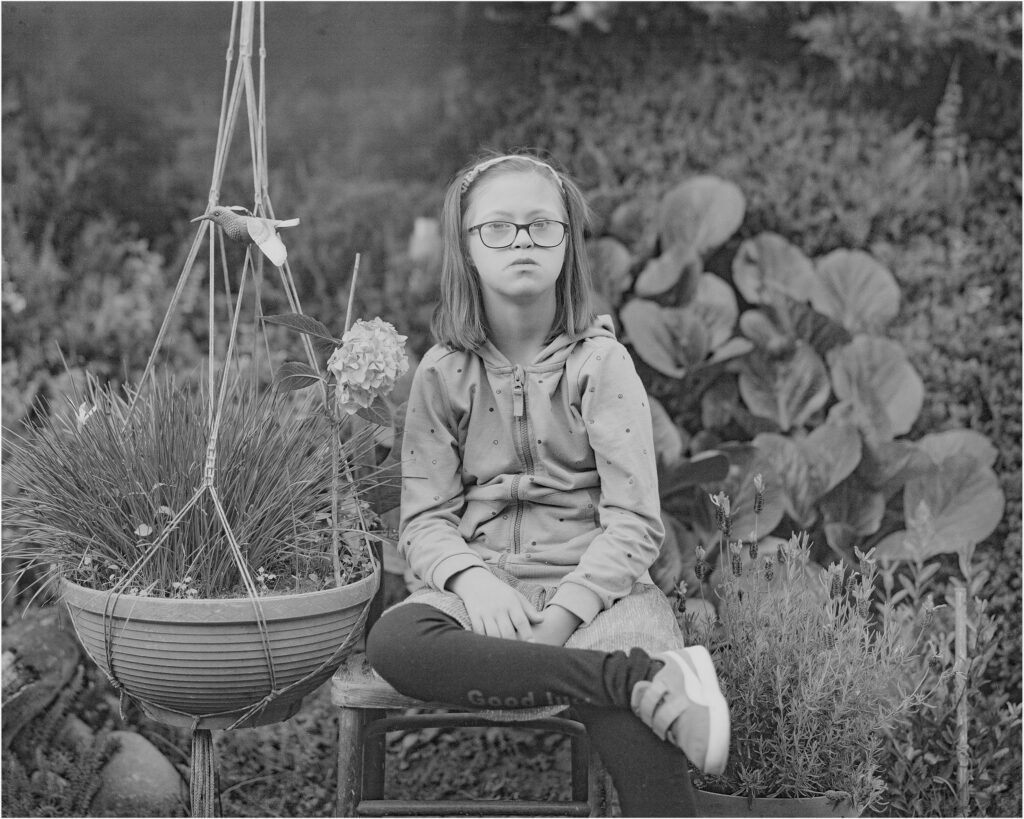

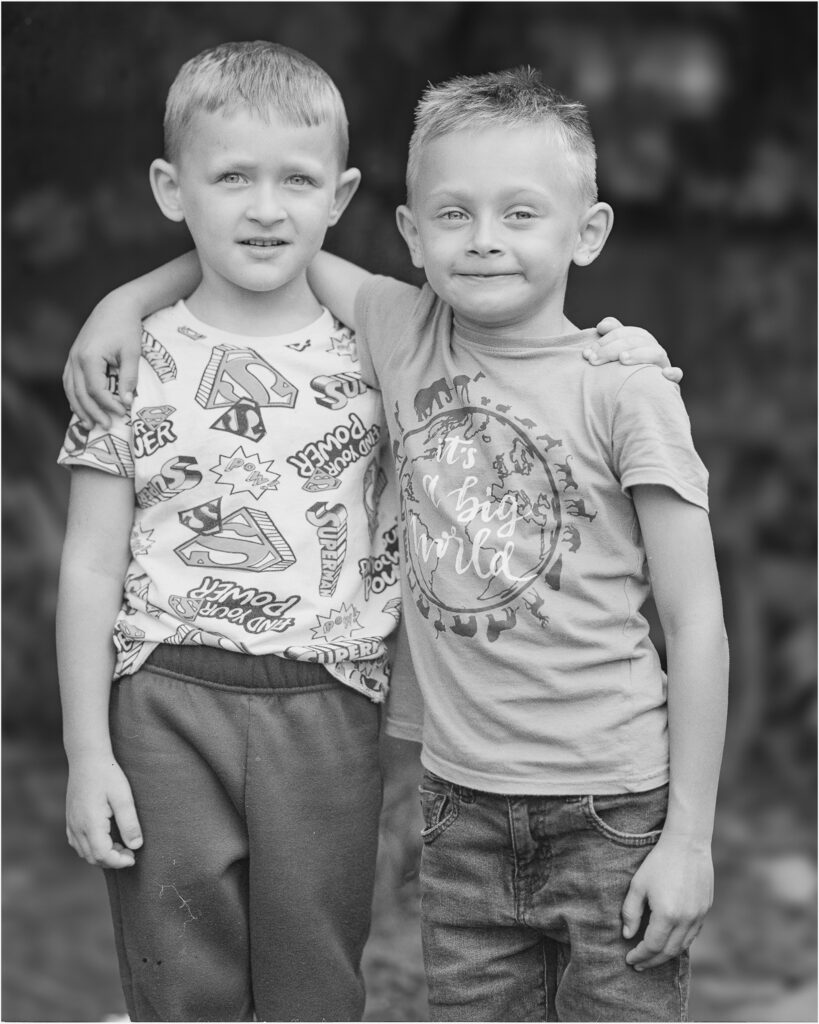

Yehor’s winning Photograph and the series “Misplaced Childhood” explores the theme of early maturity among children growing up in rural Poland. This documentary series captures the moments where innocence intertwines with responsibility, freedom with constraints, and childhood with the inevitability of growing up too soon. Through a series of black-and-white portraits, the project reflects on the lived realities of children who, while still engaged in play, are already confronting the structures of adulthood—be it through the responsibilities imposed by their environment, economic circumstances, or cultural expectations.

I sent Yehor a message from his website and he graciously responded, after a few emails he kindly and generously gifted us with not only his words but with a wealth of his delightful work and an insight into his methods and creativity.

I hope you enjoy the exchange and enjoy Yehor’s Photographs, here’s hoping we have many comments and encouragement for Yehor and other such talented Award winning Photographers to grace 35mmc and keep it deservingly as one of the most popular and best Film Photography websites on the web.

Ibraar: Could you start by introducing yourself: where are you from, what do you do, and how does photography fit into your life?

Yehor: First of all, I would like to thank you for the congratulations and for your interest in my work.

My name is Yehor Lemzyakoff, I was born in Kyiv into an artist’s family. From an early age I grew up surrounded by art — my father had his studio right in our apartment, and I was always fascinated by the way an image gradually appeared on canvas. A book about Gaudí and the boxes of Lego without instructions, gifted to us by my grandfather, left a deep impression on me as a child. These early experiences shaped my curiosity about form, composition, and the creation of images.

My path was not straightforward: I searched for myself in different areas and went through difficult times. At one point I turned to painting and created a series of abstract works, Emotional Crisis (2012), which I dedicated to my father. That project became an important therapeutic experience and made me realize that creativity is my true foundation.

In 2020 I entered the Academy of Photography in Kraków, which marked the beginning of a more conscious artistic practice. In 2023 I founded Artel Studio, a portrait studio in the heart of Kraków, and since then I have been fully supporting myself through photography. Last year I was admitted to the Institute of Creative Photography (ITF) in Opava, which became an important step towards receiving a full artistic education.

Today, photography for me is not just documentation but a way of understanding life, of seeking balance and harmony. Film and large format play a special role in this process, as each image requires depth, attention, and reflection.

Ibraar: What initially drew you to photography, and do you remember your first camera?

Yehor: I came to photography in 2008 when my father gave me my first serious camera — a Nikon D300 — and encouraged me to study at the Kyiv School of Photography. It felt like a symbolic continuation of his own artistic path. I remember how fascinated I was when making my first photographs, experimenting with different subjects and techniques.

Not long after, I experienced my first success: my very first private shoot earned me 500 dollars — far more than I expected — and gave me great encouragement. But what truly captivated me was not the commercial result, but the process itself: the possibility of observing, recording, and interpreting life through the medium of photography.

Ibraar: What inspired you to create the series Misplaced Childhood? How did you approach the project? What challenges did you face, and how did the children react?

Yehor: The series Misplaced Childhood was inspired by my own experience of early maturity and by the atmosphere of the 1990s — a difficult yet fascinating period of “perestroika.” The first photograph in the series, Young Rider (2022), shows my life partner Kasia’s nephew on a motorcycle. For me, this image became a symbol of childhood confronted too early with the attributes of adulthood.

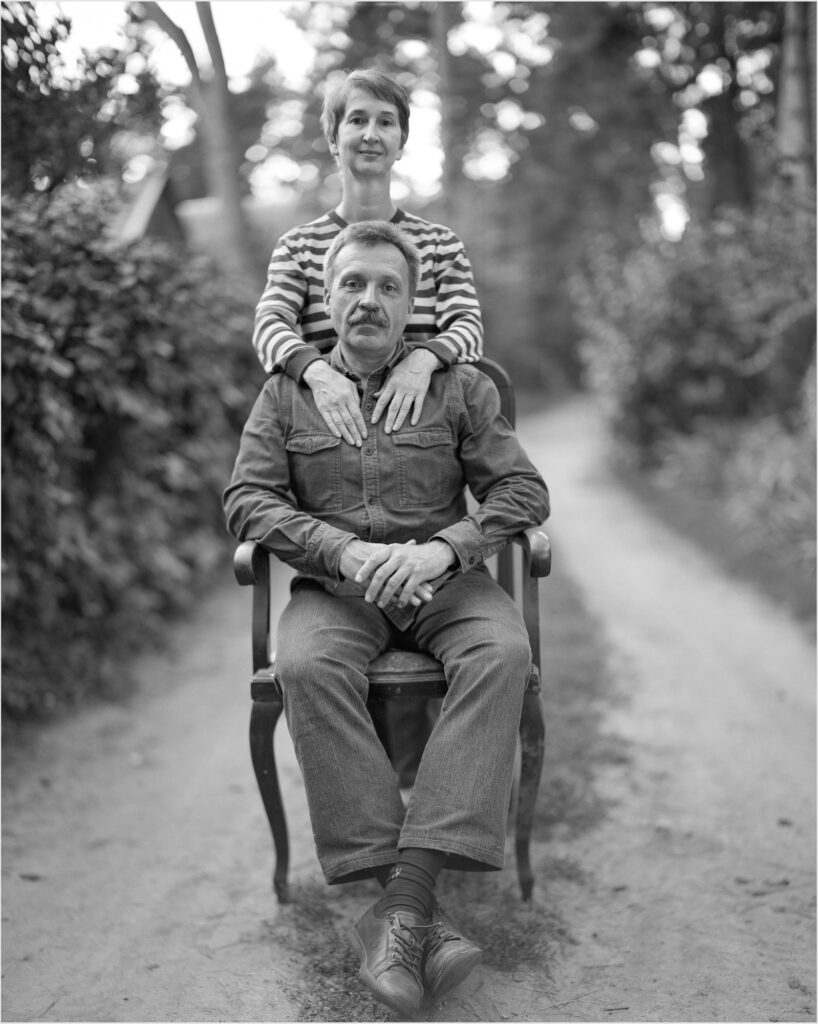

The main characters of the series are Kasia’s family: her nephews and nieces who are growing up in a village near Nowy Sącz in Lesser Poland, as well as her son, whom we are raising together.

The main challenges were technical: I was only beginning to work with large format, so the project evolved slowly. Large format demands discipline and thoughtfulness: a heavy tripod, a large format setup, repeated checks of focus and exposure before each shot. Each frame is expensive — around $30–40 for black and white, and nearly double for color. This “slow photography” trains you to be focused and responsible, in contrast to digital or mobile photography where hundreds of images can be taken almost without thinking.

It was fascinating to observe how the children reacted. They enjoyed their portraits and were curious to see themselves on film. More importantly, they felt the seriousness of the process. I noticed that when a photographer is truly demanding of himself, people in front of the camera sense it and behave differently — more attentively and consciously. Children are especially sensitive to this atmosphere, which is why such portraits become meaningful experiences for them. I have observed the same effect with adults as well.

I intend to continue this project, as it is not only artistic but also deeply personal — a dialogue with my own past.

Ibraar: What other themes and subjects inspire your creative spirit? Could you share something about your process with our readers?

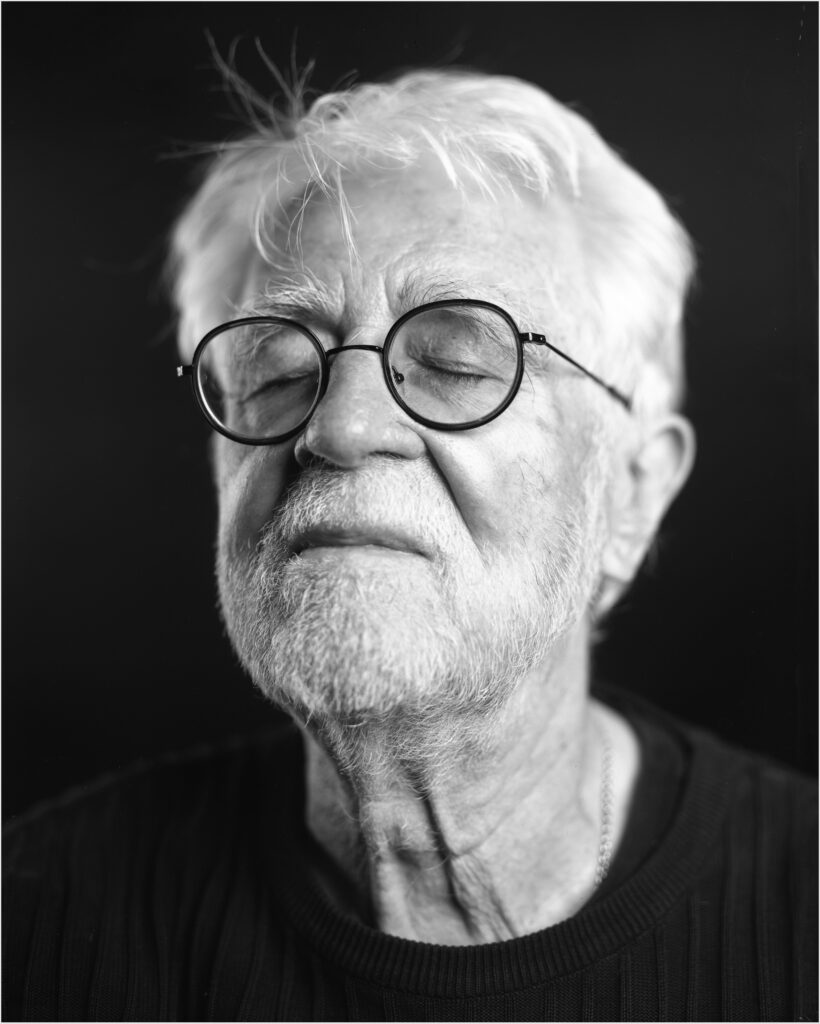

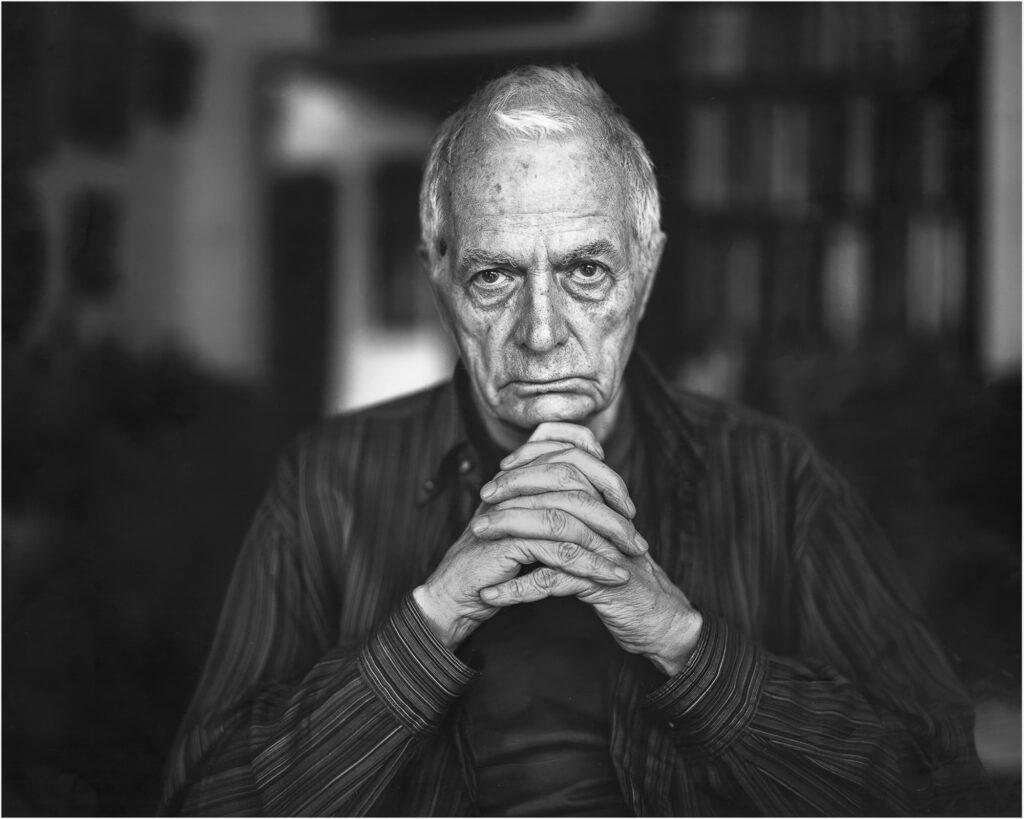

Yehor: When I studied at the Academy of Photography, I realized that I had very little experience in portraiture. So I decided to focus on it. For me, a portrait is an image that reveals personality. Just as literature creates a character or music conveys an impression of a person, a photographic portrait can show who someone truly is. Every time I take a portrait, I ask myself: who is this person?

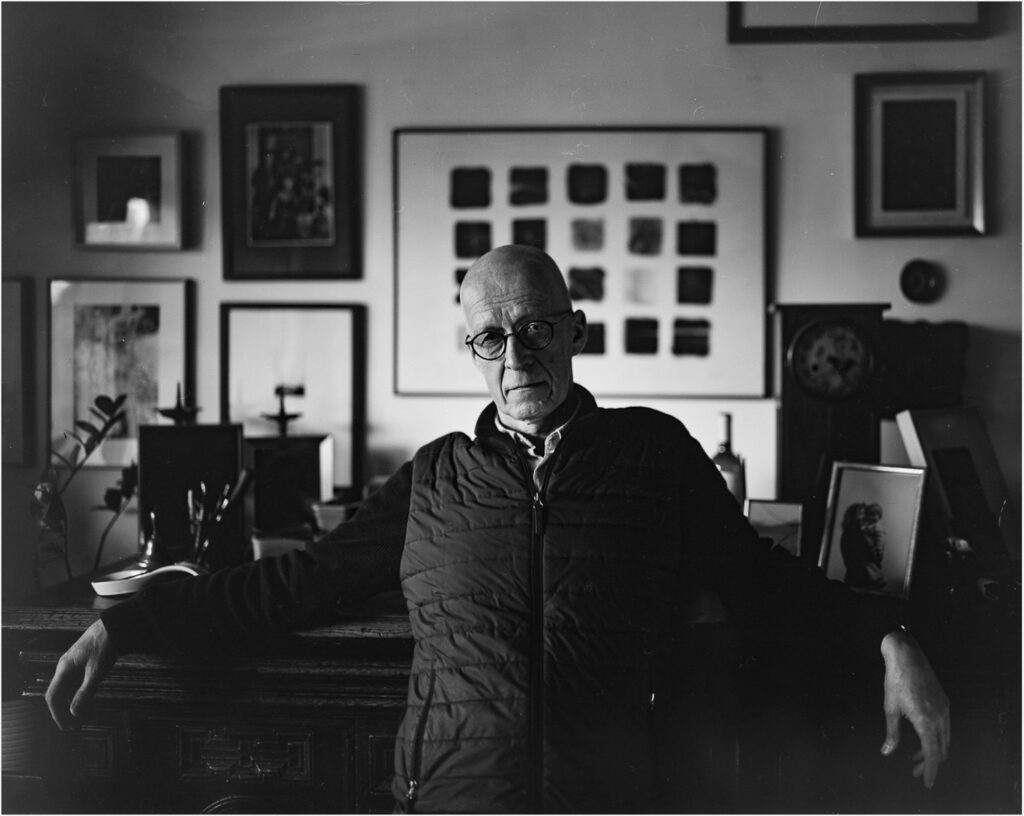

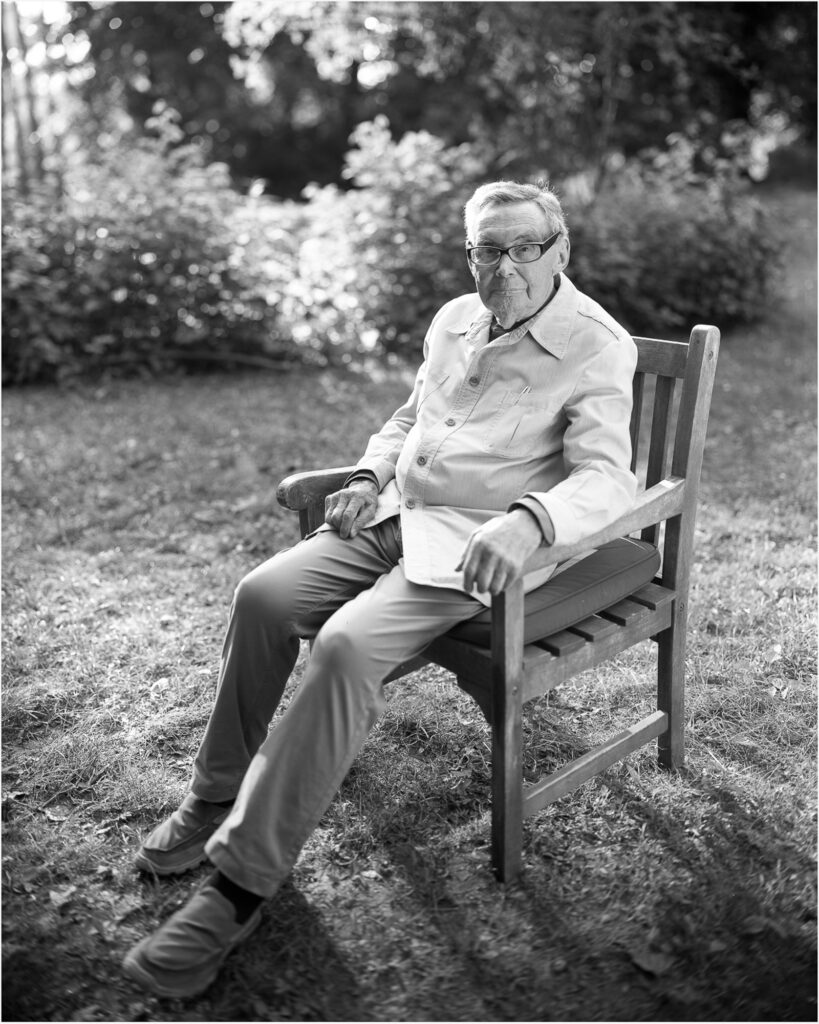

I am drawn to moments of authenticity, when a person is truly themselves — not hiding behind an emotion or a mask. To approach this, I rely on several principles of documentary portraiture: direct eye contact, the absence of forced emotions, and the subject’s connection with their environment. The background becomes part of the portrait and helps tell the story of the person.

There is one important psychological nuance: when we see a photo of someone smiling or crying, our brain immediately applies a cliché — “this is a happy person,” “this is a sad person.” By removing obvious emotional cues, we create depth. The viewer cannot instantly categorize the subject and instead begins to wonder: who is this person? That is when a genuine dialogue begins between the image and the viewer.

Ibraar: What is your favourite camera and what equipment do you use most often? Could you also share your choice of film, developing, and printing process?

Yehor: Among cameras, I especially love the Sinar P2 system — I jokingly call it a “photo-constructor.” I appreciate its philosophy and design: it is one of the most precise large format cameras, allowing extremely refined control of tilt, shift, and swing. In medium format my favourite is the Mamiya RZ67, while for my daily photo journals I often carry the compact Yashica T3. In commercial work, I mostly use the Fuji GFX.

As for film, my all-time favorite is Kodak TXP 320 — it has an incredibly beautiful grain. To my knowledge, it is one of the classic black-and-white films, used by masters such as Ansel Adams, Irving Penn, and Richard Avedon, and its emulsion has changed very little since its introduction. In practice, however, I often shoot on Ilford FP4/HP5 for their affordability, and sometimes on Fomapan 100.

One film that holds a special place in my memory is Fuji Neopan 1600. In 2009, a colleague and I managed to order 100 rolls by barter. It had uniquely expressive grain, which I loved to push two stops for an even stronger effect. Sadly, it has long been discontinued, as have many other films. Photographers must constantly adapt to these market changes and find alternative methods.

Among color films I especially value Kodak Portra 160 for its soft, pastel tones, while in slide film I prefer Provia for its vivid colors. I also love Kodak Vision cinema films (ECN-2), though I have not used them in a while.

In developing, my favorite remains the classic Kodak HC-110 (Dilution B). Sometimes I experiment with German SPUR developers — they give excellent results, though the process is much slower.

As for printing, I particularly enjoy contact printing, and working in the darkroom is always a special experience for me. I have not yet printed optically from 8×10”, but I plan to produce a small edition that way. More often, however, I scan my negatives and print using an inkjet plotter.

Ibraar: How did you feel after receiving the award? How has your life changed since?

Yehor: The next day I had a terrible hangover… just kidding 🙂 In reality, I was both surprised and delighted, as I truly did not expect to receive such recognition.

I have a somewhat unusual relationship with an artistic career — it goes back to the time when I practiced amateur boxing. I am very demanding of myself and tend to see art as a kind of competition with my own ego. Achievements bring me joy, but I constantly ask myself: why am I doing this?

In that sense, the award was a manifestation of the process of self-actualization. At the same time, it reminded me how important it is to remain honest — with oneself and with others — and to be aware of the responsibility that comes with recognition.

To be honest, I still feel that I am only at the beginning of my artistic journey.

Ibraar: And finally, what plans do you have for the future and would you consider writing an article for 35mmc?

Yehor: My plans are quite simple and tied to what I believe is a universal recipe for success — consistency and determination. So my plan is to work, work, and work again (and I wish the same to others as well).

I would be delighted to write an article for 35mmc 🙂

Links

https://www.vogue.com/photovogue/photographers/248564

https://www.saatchiart.com/yehorlemzyakoff

Share this post:

Comments

Gary Smith on IPA 2025 International Photographer Of the Year Yehor Lemzyakoff on Misplaced Childhood and his Photography

Comment posted: 31/08/2025