There was a point in the late 70s when Minolta did something mildly uncharacteristic.

They had always produced interesting cameras with cutting-edge features, but occasionally they were aesthetically challenged – the SRT 101 was gawky while the XK/XM/X-1 (with certain finders at least) could look quite monstrous.

But in 1977, they produced a cutting-edge camera using the latest technology and high-spec metering, and it was actually a looker. That camera was the XD7 (in Europe, XD11 and XD elsewhere). This is not a review of that camera. It was the start of a trend that lasted a couple of years.

Alongside the top flight metal shutter, multi-exposure mode, silicon photocell camera, Minolta released a budget version offering similar specs, but using older, more established technology; they called this the XG7 (in Europe, XG2 and XG-E elsewhere). Two years later, they produced an updated camera to succeed the XG7 that provided all the features a keen photographer could want (at the time). That camera is the subject of this review; it was called the Minolta XG9 (XG-S in Japan).

The Minolta XG9

The Minolta XG9 features:

- A full information viewfinder which shows you the aperture set via an ‘Aperture Direct Window’ (ADW) along with the associated shutter speed selected when the camera is set to Auto. Speeds are shown on the right side of the viewfinder with a little red LED next to each,

- Minolta’s ‘accu-matte’ focusing screen with a split-image rangefinder at the centre of the screen surrounded by a microprism ring.

- a touch-sensitive shutter button to turn on the electronics and save batteries,

- an electronic self-timer,

- a battery check for the readily available Silver-Oxide batteries,

- settings to alter exposure by 2 stops in half-stop increments in either direction while in ‘Auto’,

- a depth of field preview button,

- a threaded port for a mechanical cable release,

- a ‘safe load’ indicator,

- a compact, lightweight body, and

- The ability to attach Minolta’s standard Minolta ‘G’ autowinder.

Economies

So, where were the economies made? Mainly in areas that don’t hold the camera back too much.

- The Shutter is a conventional horizontally-running cloth unit, which limits the synch speed to 1/60th, but it is electronically controlled to give continuously variable speeds as required. The XDs had a vertical-running metal shutter.

- The metering uses CdS cells, which don’t react as fast as silicon photodiodes as used on the XDs, but as they don’t need to meter in the fraction of a second between frames that would be required for a motor drive camera, and they don’t need to work fast enough to cut-off on-camera flash, they easily suffice.

- The top-plate is moulded in plastic with a copper coating and a chrome layer on top (it was also available in black).

Although the cloth shutter is hardly cutting-edge, a similar setup was used in a number of highly respectable cameras, such as the OM2 and Pentax MX. CdS cells are highly capable and were widely used by the bulk of manufacturers, the main advantages of the speed of silicon photo cells was for flash metering or judging exposure in the fraction of a second while the mirror was down in high speed motordrive cameras.

For an enthusiast on a tight budget, the Minolta XG9 must have looked like a well-specified and highly attractive option.

A look around

The user experience

The main thing missing is an exposure lock. The compensation function works, but you have to press a button to get off pure auto. At one point my finger slipped and I tripped the shutter by mistake. A lock would have been faster and easier.

Downsides

Minolta never shied away from innovation. These cameras relied heavily on electronics that were quite new at the time. Time (to be fair, a lot of time – 45 years) has not been entirely kind.

My Minolta XG9 needed the batteries loaded for a while before it would function – I’m guessing some capacitors were not charging as quickly as they originally did. Sometimes the camera would refuse to show any LEDs in the viewfinder and had to be set to a manual exposure, but then Auto would spark into life again after a manual shot (note that the shutter fired, so it was still getting power). On my copy the LEDs, are looking rather tired and a bit dimmer than is ideal. On the whole, I find that a plain needle against a scale or an LCD readout below the screen tend to survive better than a row of LEDs, but your mileage may vary.

Minolta top-plates always did tend to be a bit thin on some of the standard models – this is why some of them have the extra crease along the front and back edges (this can be seen on the OM1 and 2, which also have rather thin top-plates). Dented 101s are quite common. The XG9 top plate is not made of metal. Engineering plastics can be excellent for top plates, but the material used for the XG9 top-plate does not appear to be anything special – it is quite insubstantial and is covered in thin coats of copper and chrome that only seem to perform a cosmetic function. The top-plate of my XG9 shows a fair degree of suffering – it has a crack at one end and the chrome film on top of the plastic has discoloured and pitted rather badly.

Pictures

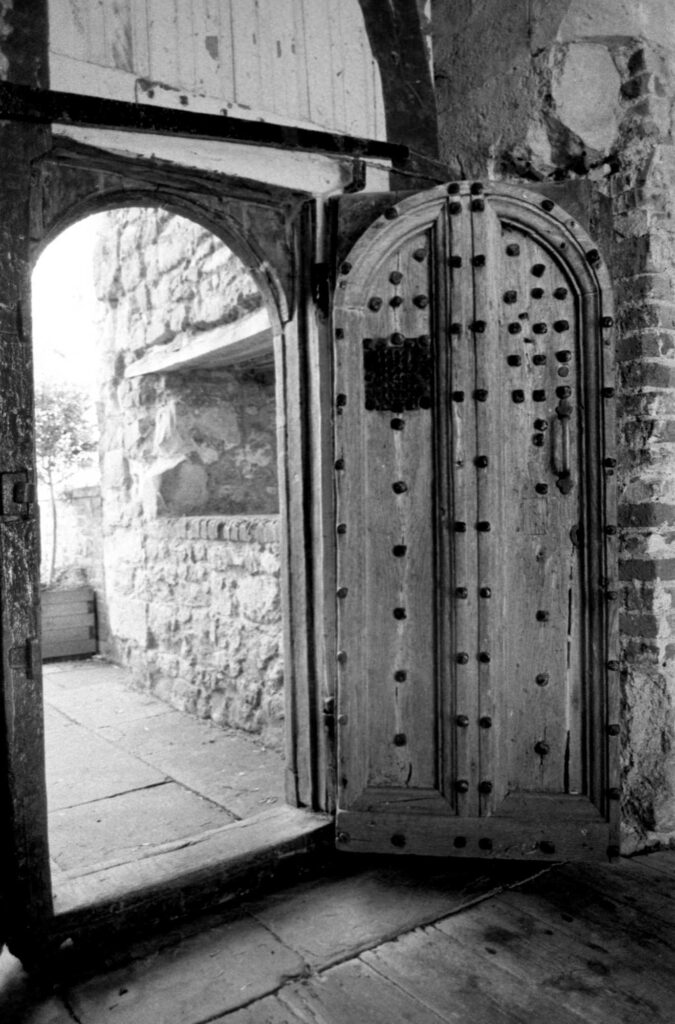

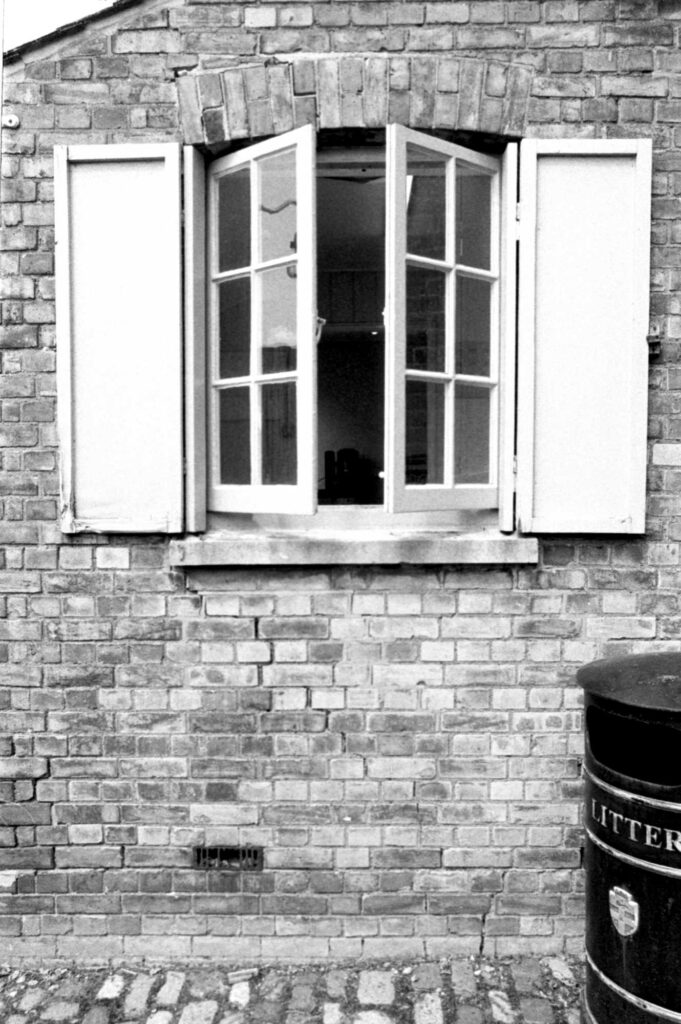

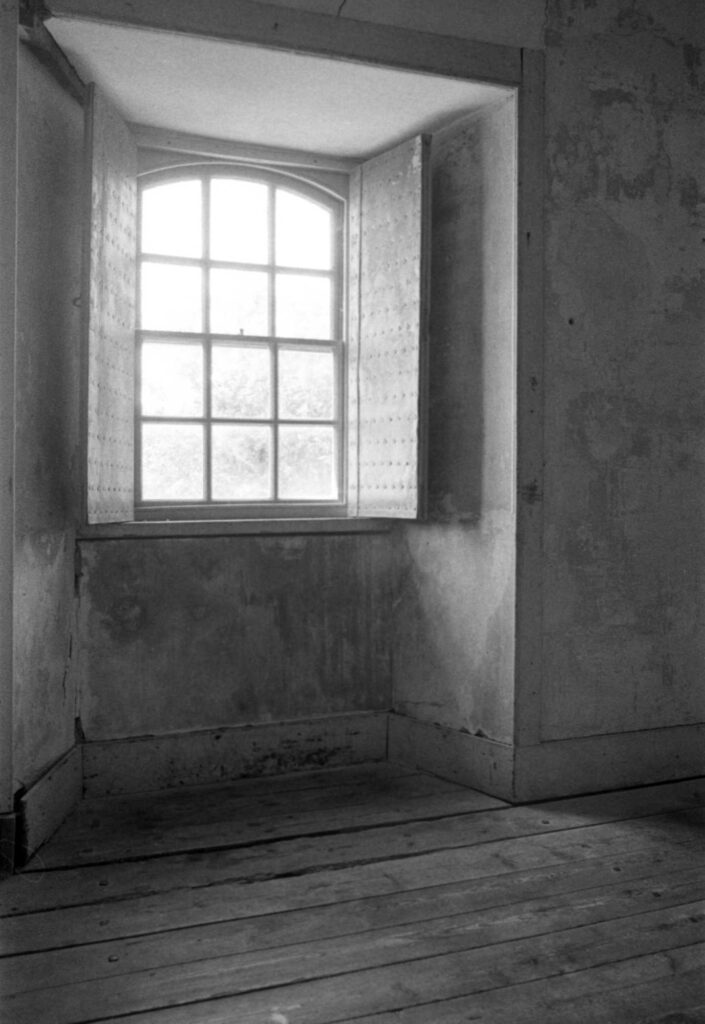

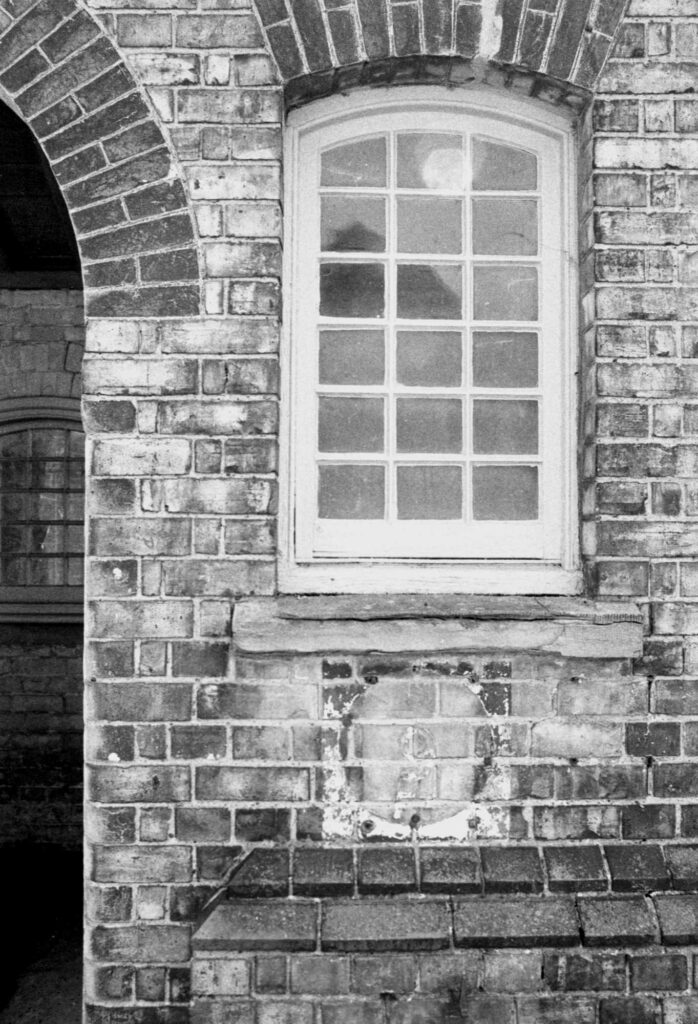

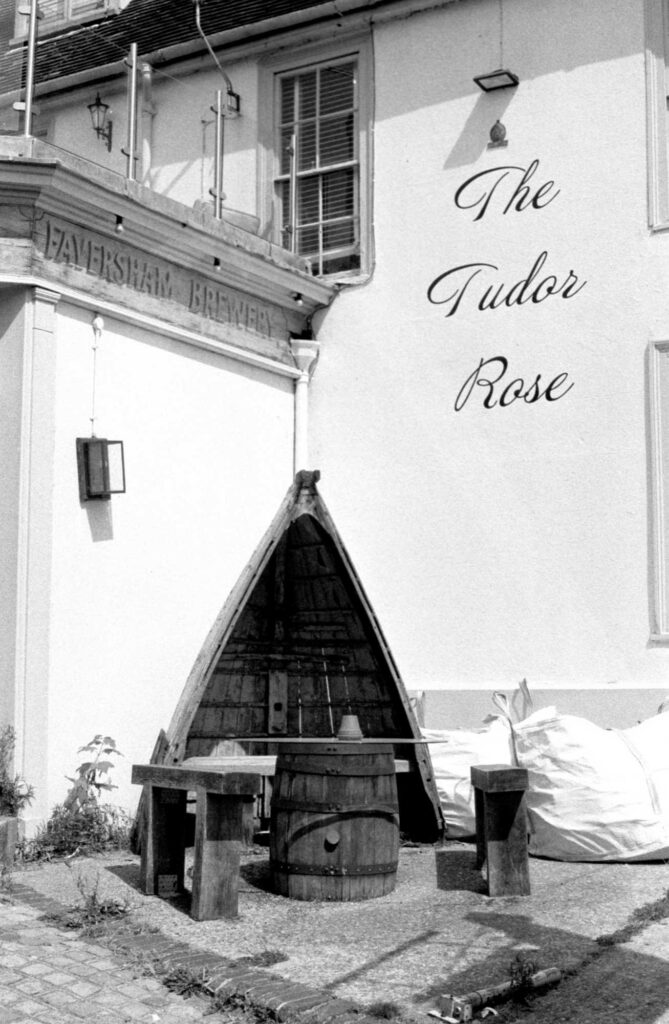

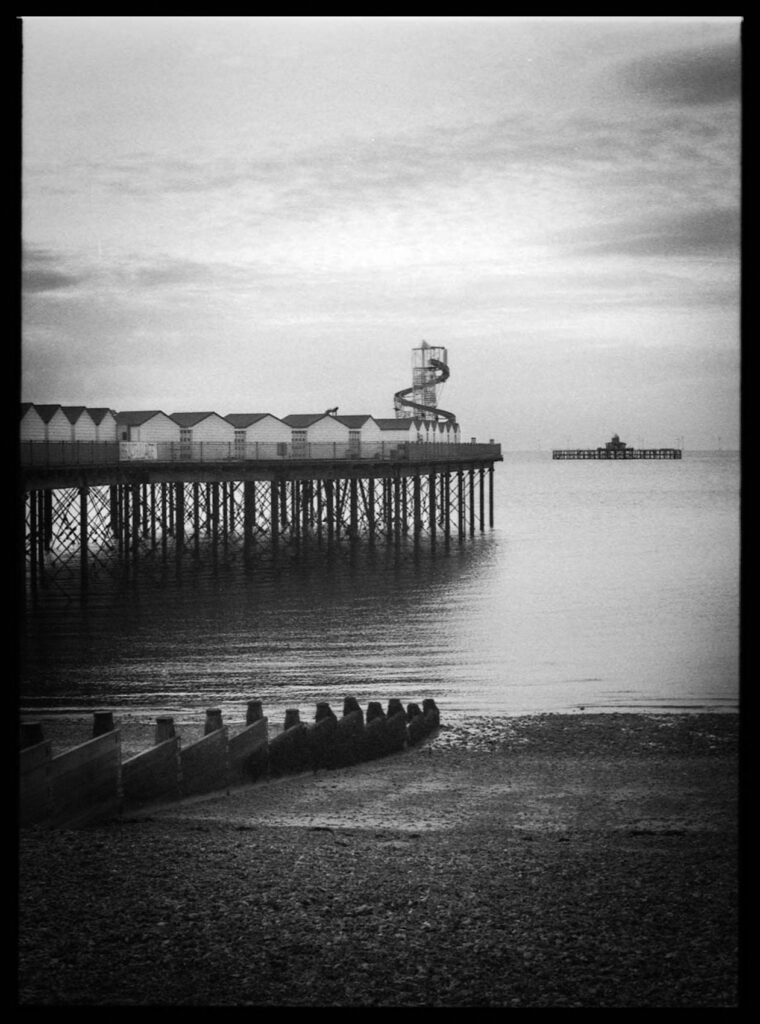

These shots were taken on a trip to Upnor and Rochester. Lenses were Rokkor 50/1.4, Rokkor 45/2.0 and Marexar-CX 28/2.8, film was Kentmere Pan 400, processed in RD09.

Upnor Castle, front gate

Conclusion

The Minolta XG9 a good looking camera and I was happy with the pictures it produced. I always liked the old Minolta logo. This was about the last camera to have it before they adopted the more ‘shouty’ capital MINOLTA logo with the rising sun in the ‘O’ (although I’ve always thought it looked more like a cricket ball to be honest).

The main reason I probably won’t end up running another roll through this particular camera is the flakiness of the ageing meter requiring periodic shots to taken with manual exposure.

At the end of the day, the camera I still tend to reach for when I want to use a Rokkor lens on film is my SRT 101 (seen below posing as a ‘Super’).

After the Minolta XG9

The Next generation of cameras was just around the corner. The XG9’s place was taken by the XG-M – similar specs to the XG9 with more brutal styling and the capacity to support a 3.5 frames per second motordrive.

Fairly soon, the X-700 took the horizontal shutter of the XGs and combined it with a program mode, more sophisticated photocells, and useful features like an exposure lock. Budget models like the X-500 and X-300 added improved manual exposure features. SR mount cameras survived the dominance of autofocus and were still being produced well into the 2000s, up to within a year or so of Minolta getting out of cameras entirely.

Lots of interesting stuff about SR-mount lenses and cameras can be found at The Rokkor Files, where you can even download the font used for the old Minolta logo.

Share this post:

Comments

Geoff Chaplin on Minolta XG9 review

Comment posted: 25/08/2025

Comment posted: 25/08/2025

Carl Follstad on Minolta XG9 review

Comment posted: 25/08/2025

Comment posted: 25/08/2025

Gary Smith on Minolta XG9 review

Comment posted: 25/08/2025

Are the cameras you review ones that you've had since day one? All of the film cameras that I write about have been new additions rather than ones I've owned forever.

Comment posted: 25/08/2025

Comment posted: 25/08/2025

Alexander Seidler on Minolta XG9 review

Comment posted: 26/08/2025

Comment posted: 26/08/2025

Keith Drysdale on Minolta XG9 review

Comment posted: 26/08/2025

Comment posted: 26/08/2025

JC on Minolta XG9 review

Comment posted: 26/08/2025

It's nearly as small and lightweight as a Pentax MEsuper ! I prefer it about the Minolta XE cameras who are large and heavyweight.

Furthermore the viewfinder is as bright as a Minolta XD 7 !

Furthermore you can read the aperture and the shutter speed in the viewfinder.

The XG 9 was the predecessor of the XG-M. Both are the top of the whole XG series.

I can highly recommend both the XG 9 and the XG-M for all beginners and for all advanced analogue photographers !

Comment posted: 26/08/2025

Jeffery Luhn on Minolta XG9 review

Comment posted: 26/08/2025

Very nice set of photos! I think you could produce good shots with almost any working camera. I had an SRT 101 on loan for a while back in the late 1970s and it performed well, but the meter was inconsistant. That made me think Minolta was a clever company that occasionally over reached on their cameras. I went to Nikon and never looked back. For handheld light meters, Minolta was great. I still have a Minolta flash meter that also does a great job as an incident meter. Been flawless for nearly 30 years! Obviously a company with many divisions.

In closing: Carefully composed and processed film taken with any number of models can yield great results, as you've demonstrated. We're lucky to live in a time where we can scoop up working vintage cameras on ebay. I'm currently enjoying a Rolleicord TLR and a cute little Zeiss Contessa 35mm. This stuff is so darn fun! Keep shooting and writing!

Comment posted: 26/08/2025