I’ve always been fascinated by the square format. As a longtime 35mm SLR shooter, I never really experienced different aspect ratios—except through cropping in post. My journey in photography started with a couple of Minolta 35mm autofocus SLRs back in the late ’90s. I began with Fuji color negatives and later switched mostly to color slides. Fuji Sensia 200 was my affordable slide film of choice, with the occasional Kodak E100VS when I wanted more vivid colors. Fast forward to 2004—I switched to digital with a Nikon D70 and kept riding the upgrade train all the way to a D850. After 20 years of digital, I found myself itching to get back to film.

My return to film photography started when I walked into a local used camera store and asked for a Nikon film body with autofocus so I could use my existing lenses. I hadn’t made the switch to Nikon’s mirrorless system yet. I walked out with a Nikon F90X and a couple of rolls of Kodak Tri-X excited to be shooting film again. It was refreshingly affordable compared to the cost of a brand-new, top-of-the-line digital camera from Nikon, Canon, or Sony.

Not long after that, I picked up a Contax T 35mm compact rangefinder. Suddenly, I was bitten by both the rangefinder bug and the black-and-white film bug. But I was still shooting a 3:2 aspect ratio. That itch to explore square format hadn’t gone away.

I’d always been fascinated with the Hasselblad, but it felt too expensive for what it was. Now that I was back shooting film, I kept asking myself—why spend so much on a camera body when, in the end, it’s the same film stock? In my digital years I bought expensive cameras for better sensors. With film, I didn’t feel that pressure anymore. Coming back to film was liberating—no need to chase the latest or most expensive gear.

My interest in the Hasselblad was as much about shooting medium format as it was about shooting square format. So I took a detour and picked up a Mamiya M645 system. That got me hooked on medium format. At this point, I was deep into rangefinders, black-and-white film, and medium format—but I still hadn’t made it to my goal: shooting 6×6 square medium format.

Eventually, I discovered the Mamiya 6 rangefinder released in 1989. After watching a bunch of YouTube reviews, I decided I wanted to try one. When I finally handled one at a camera store, I liked how it felt in hand, the viewfinder was excellent, and I liked that it had interchangeable lenses across three focal lengths. But in the end, the Mamiya 6 felt too expensive for a camera I wasn’t sure I’d carry often. These days, now that I’m no longer shooting professionally—and don’t have photo assistants to lug around my gear—small size and portability suddenly matter a whole lot more. For the past few years, my mantra has been: the best camera is the one you have with you. Unfortunately, that often means relying on my iPhone more than I’d like. I’m sure many of us can relate.

Then, while browsing vintage cameras at a local camera store, the Mamiya Six caught my eye—a folding medium format 6×6 rangefinder from the ’40s and ’50s. I thought of it as the grandfather of the 1989 Mamiya 6. It was compact when folded, shot 6×6 square medium format, and—most importantly—was cheap enough for an impulse buy. So much so that I bought one without inspecting it too closely… and ended up with a lens that had way too much haze. I’d always used modern gear and had little experience evaluating vintage optics. I didn’t know what to expect. Now I do!

This was my first time shooting with a truly vintage camera. One roll of Tri-X 400 later, and I was hooked. The camera was just so much fun to use. But the photos? Not great. The haze caused a lot of veiling flare and low contrast. Still, I enjoyed shooting that first roll so much that I felt a strong urge to find another Mamiya Six in better condition. So, back to camera hunting I went.

I’m fortunate to live in Bangkok, Thailand—a city with dozens of used and vintage camera stores. It makes camera hunting a lot more fun (and a little dangerous for the wallet). I found another Mamiya Six IV at a different local shop—this one had clearly been repaired and modified over the years. The bellows had been replaced with a red one, and the film winding knob looked like it wasn’t original. The markings didn’t match the usual style, so I suspect it was either a custom repair job or taken from another model. The body wasn’t in great shape, but the lens was in much better condition—just a few cleaning marks and, thankfully, no haze. I asked the shop owner, who also happened to be a camera technician, if it was possible to swap the lens from this camera onto the one I already had. Since both used the same lens and shutter assembly, he said it was not only possible, but easy. A deal was made, and a few minutes later, the lens had been swapped. This second body cost even less than the first one—but between the two, the costs were definitely starting to add up.

The Mamiya Six was produced in 16 different versions between 1940 and 1958—something I learned from this excellent video. Both of my cameras turned out to be the Mamiya Six IV, the first model released after World War II. They’re foldable medium format rangefinder cameras from 1947 that shoot 6×6. Both my cameras feature the same Olympus Zuiko 75mm f/3.5 lens paired with a Seikosha-Rapid shutter.

Unlike most cameras where you focus by moving lens elements, the Mamiya Six focuses by physically shifting the film plane forward and backward inside the camera body. You control this using a thumbwheel on the back of the camera. It’s a unique system, but surprisingly I got used to it pretty quick.

Advancing the film doesn’t cock the shutter. Aperture and shutter speed are set on the lens. Manually cocking the shutter and adjusting settings can be a little fiddly—I’ll admit, I still forget to cock the shutter before taking a shot. There’s no built-in light meter either, so I use the Lightme app on my iPhone to get my exposures right.

So how did the new lens perform? Quite nicely! The cleaning marks didn’t seem to affect anything, and the uncoated lens with its simple optical design gives the images a vintage look. Wide open, it’s a bit soft, and the depth of field can be too shallow for some subjects—but overall, I’m happy. Shooting at f/5.6 to f/11 seems to be the sweet spot. With a maximum shutter speed of 1/500th of a second and a minimum aperture of f/22, it handles most daylight conditions just fine with Kodak Tri-X 400. Mission accomplished: I’m finally shooting square!

Shooting medium format slows everything down. You only get 12 frames per roll. I tend to judge a roll by how many “keepers” I get—and sometimes, that’s not many. But that’s also part of the charm. Fewer frames make me think more carefully about what I’m doing.

And that square format itch? Definitely scratched. Framing the world with a square frame adds a new layer of enjoyment to the whole process. I find the square format great for static scenes, though I think it’s a bit less effective at conveying motion—maybe I just need more practice thinking square.

I’ve come to realize that part of the fun in photography, for me, comes from the limitations. With modern digital cameras—electronic viewfinders, AI autofocus, wide dynamic range, low noise, instant ISO changes, and endless lens options—it’s easy to get a technically good photo in just about any situation. But with a vintage camera, black-and-white film, a fixed 75mm f/3.5 lens, and limited shutter speeds, I have to work within a smaller envelope. And that pushes me to be more intentional—to think about the light, and to better anticipate the moment. They say constraints fuel creativity. I think this experience proves that.

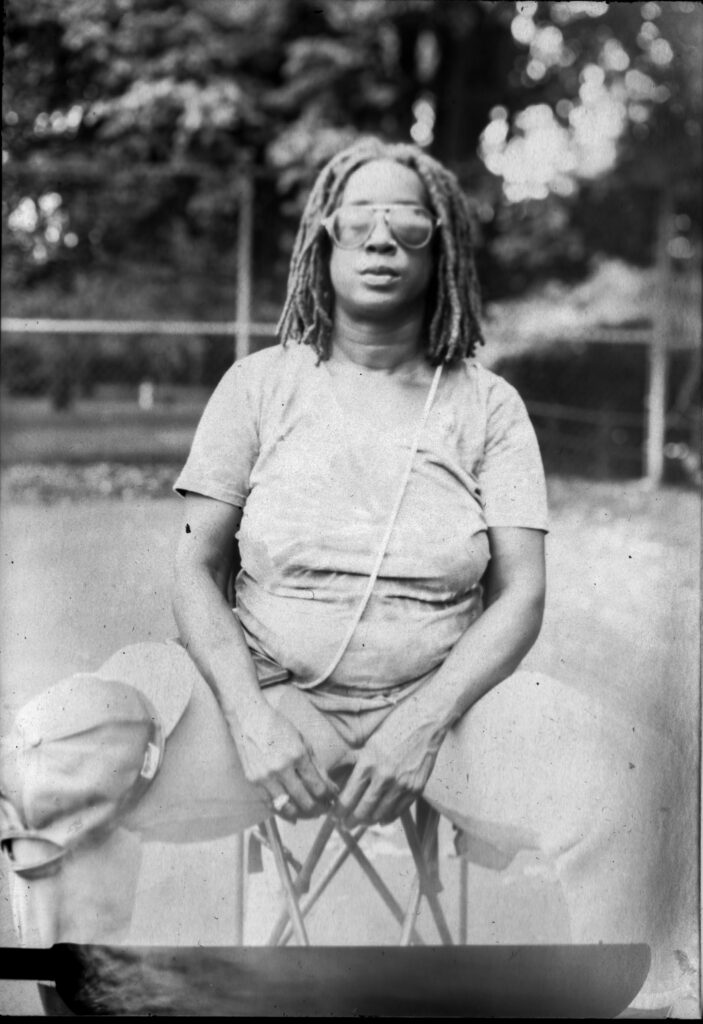

I’ll let the photos speak for themselves. Time to buy more film!

Share this post:

Comments

Michael Zwicky-Ross on Mamiya Six IV – Exploring Square Format with a Vintage Camera from 1947

Comment posted: 12/09/2025

Comment posted: 12/09/2025

Comment posted: 12/09/2025

Thomas Eland on Mamiya Six IV – Exploring Square Format with a Vintage Camera from 1947

Comment posted: 12/09/2025

One is a iv b and the other a K.

One is 6x6cm and the other 6x6/6x4.5 dual format.

I was mostly shooting digital when I lived in Thailand.

How are processing and film costs there now?

Comment posted: 12/09/2025

Comment posted: 12/09/2025

Jeffery Luhn on Mamiya Six IV – Exploring Square Format with a Vintage Camera from 1947

Comment posted: 12/09/2025

Thanks for your posting. I'm a big fan of 6x6 cameras. Rollei, Zeiss, Mamiya TLR, and especially the Mamiya 6 you have. I have an old one and a newer model that cocks the shutter. Dollar for dollar, the Mamiya 6 is a great bargain for the quality. I just did some shots of me and my 78 year old brother yesterday! I'll process the film today. GREAT CAMERA!!!! Always attracts attention from other photo bugs!

Gary Smith on Mamiya Six IV – Exploring Square Format with a Vintage Camera from 1947

Comment posted: 12/09/2025

My Mamiya shoots 6 x 4.5, whereas my Perkeo II folder shoots 6 x 6. The Perkeo is lighter and easier to handle and as an added bonus it fits in my jeans pocket!

Thanks for your article Danai!

Geoff Chaplin on Mamiya Six IV – Exploring Square Format with a Vintage Camera from 1947

Comment posted: 13/09/2025

Comment posted: 13/09/2025

Russ Rosener on Mamiya Six IV – Exploring Square Format with a Vintage Camera from 1947

Comment posted: 13/09/2025

Nothing beats medium format black and white. Each photo feels like an engraving. That's cool Thailand has a lot of vintage camera shops and technicians. One day I will have to visit!

Thanks for this review.

Richard Watson on Mamiya Six IV – Exploring Square Format with a Vintage Camera from 1947

Comment posted: 19/09/2025