I’ve always felt a kind of disgust toward the trend of full automation and burst shooting. I call it spray and pray. The camera sets the exposure, detects a smile, locks on an eye, fires a dozen frames in a second, and the user just picks one.

Sometimes I wonder what comes next. It could be an AI-powered drone that knows where to go, what to frame, and when to press the shutter, while the so-called photographer lies in bed, scrolling through his phone.

That sounds pathetic, doesn’t it?

But it’s probably only the beginning of something far more frightening, though perhaps fascinating for some.

One day AI will know you better than a mirror. It will store a 3D model of every square millimetre of your skin and every detail you are not even aware of, and it will be able to generate a perfectly believable picture of you sitting in a bar you’ve never entered. The image could be so flawless in every detail that no one, not even you, could tell whether it really happened.

Essentially, photography is an act of recording, whether the purpose is to restore and represent the visible world, or to express ideas and emotions. As a medium of recording, it has always depended on physical reality and presence. The reality is that the light reflected by tangible objects in a scene reaches the sensor, whether it’s film or CMOS. The presence is that the subject must truly exist in front of the lens, actively or passively, at the very moment that the photo is taken.

But once AI becomes capable of creating a frame indistinguishable from a real photo, all that physical reality and presence lose their meaning. A photo can no longer prove that something ever existed. And the skills we’ve gained for expression, including reading light, composing, capturing the right moment, will be no better than what a supercomputer can simulate.

People say machines can never fully replicate a human touch, those beautiful mistakes, the imperfections that keep art alive. Nope. Given enough time to learn, AI can reproduce those flawed human traces too, if that’s what people want. And no one would tell the difference.

Then comes memory. If everyone believes an image showing you drunk and dancing under a beam of afternoon sunlight thirteen years ago, and keeps reminding you of that beautiful moment, will you start to ‘remember’ it too? You can almost feel the sweat, the sound of laughter, and the trembling in your knees.

Memory has never been a perfect record. Each time we recall it, we rebuild it by adjusting colors, softening edges, or filling gaps with imagination. That gives AI a chance to reshape how we remember. Once machines learn to generate images, sounds, and stories that resemble our memories with perfect precision, the brain may no longer care whether something truly happened. It will accept some memories being partially completed, adjusted, or polished by algorithms that know our faces, our friends, our pasts, as long as it feels real. Over time, those generated fragments might weave themselves into genuine recollections until… even our emotions begin to rely on moments that never existed.

That day will come. Perhaps you and I, as photographers, will live to see it happen. And when that day comes, can you confidently tell which part of your memory is true, and which part is fabricated?

Can you?

P.S.

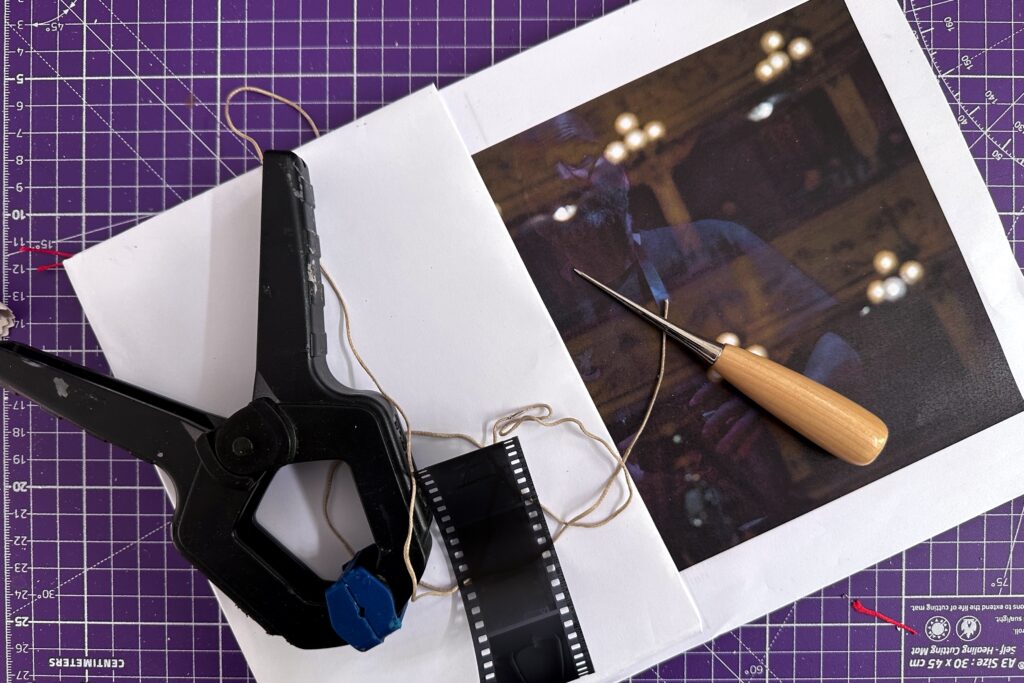

1. Credit: model Daihi (大飛), photographed July 2017 at a local dance academy.

2. The paragraph beginning with ‘Memory has never been a perfect record’ was written and inserted there by ChatGPT after reading my original draft, a small demonstration of how AI-generated information can naturally merge with what we call ‘real’.

Share this post:

Comments

Charles Young on Do You Remember That Drunk Dance Thirteen Years Ago?

Comment posted: 25/11/2025

Chuck

Comment posted: 25/11/2025

Charles Young on Do You Remember That Drunk Dance Thirteen Years Ago?

Comment posted: 25/11/2025

Chuck

john on Do You Remember That Drunk Dance Thirteen Years Ago?

Comment posted: 25/11/2025

Comment posted: 25/11/2025

David Pauley on Do You Remember That Drunk Dance Thirteen Years Ago?

Comment posted: 25/11/2025

Comment posted: 25/11/2025

Comment posted: 25/11/2025

Comment posted: 25/11/2025

Comment posted: 25/11/2025

Peter Schu on Do You Remember That Drunk Dance Thirteen Years Ago?

Comment posted: 25/11/2025

Comment posted: 25/11/2025

Gary Smith on Do You Remember That Drunk Dance Thirteen Years Ago?

Comment posted: 25/11/2025

Comment posted: 25/11/2025

David Kieltyka on Do You Remember That Drunk Dance Thirteen Years Ago?

Comment posted: 25/11/2025

Comment posted: 25/11/2025

Geoff Chaplin on Do You Remember That Drunk Dance Thirteen Years Ago?

Comment posted: 26/11/2025

I recognise I am an animal and wish to stay that way. Augmented reality, current, past and future is not fo me. AI as a tool used responsibly and under supervision may be acceptable, but as Socrates knew any system of control can and will be corrupted at some point.

Comment posted: 26/11/2025

Comment posted: 26/11/2025