Today there are many options for converting colour and b&w negatives to positives that combine hardware and software. In contrast to now, when I embarked on this journey, th...

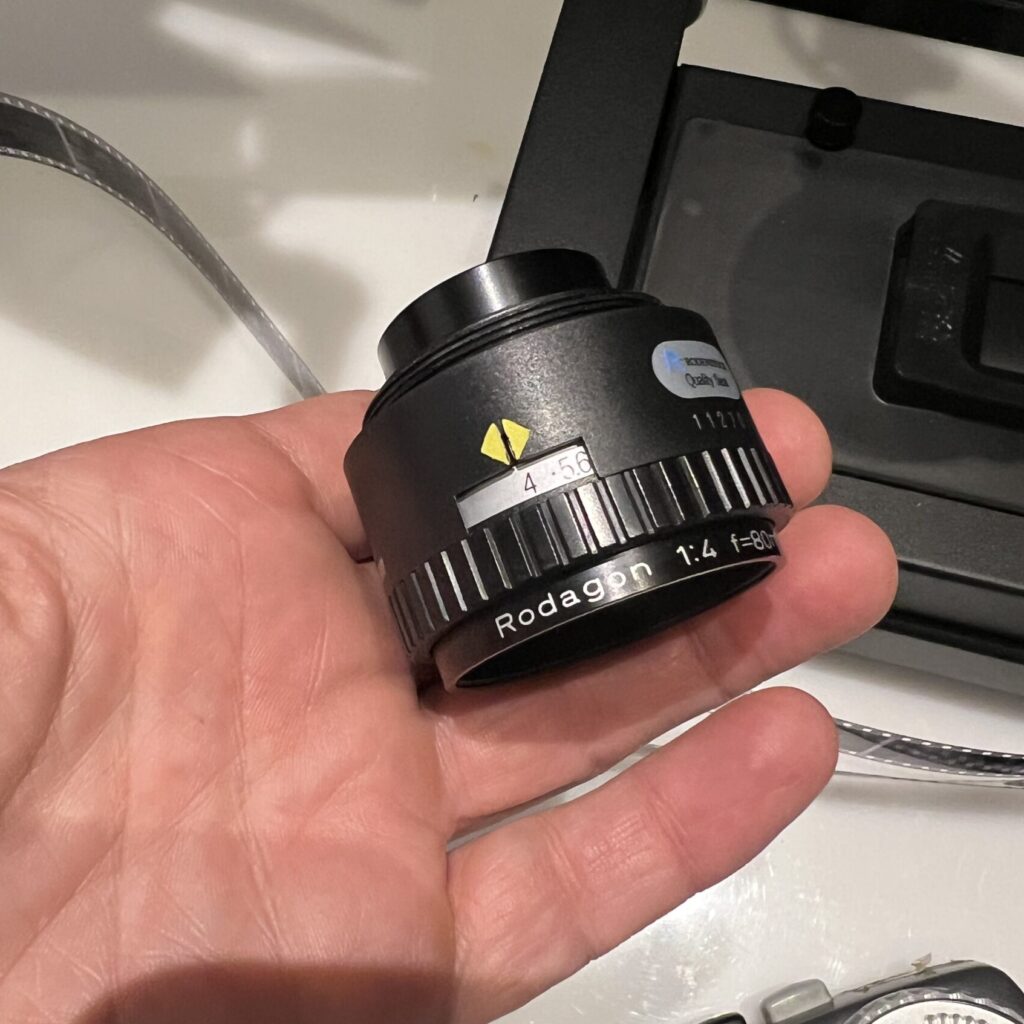

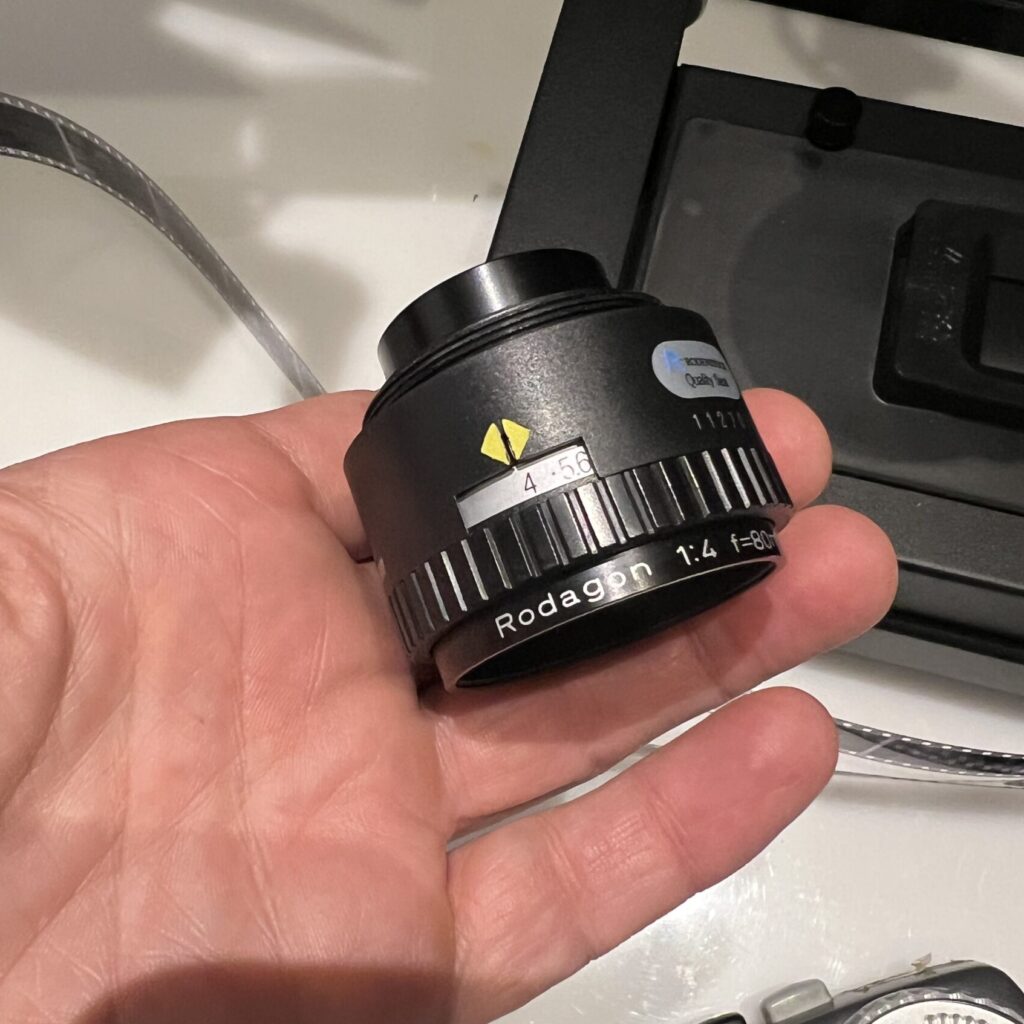

You can fall in quite a huge rabbit hole if you read about scanning negatives with your mirrorless or DSLR camera, lots of people recommend different lenses. You easily can spen...

Today there are many options for converting colour and b&w negatives to positives that combine hardware and software. In contrast to now, when I embarked on this journey, th...

A method for inverting colour negatives in software.

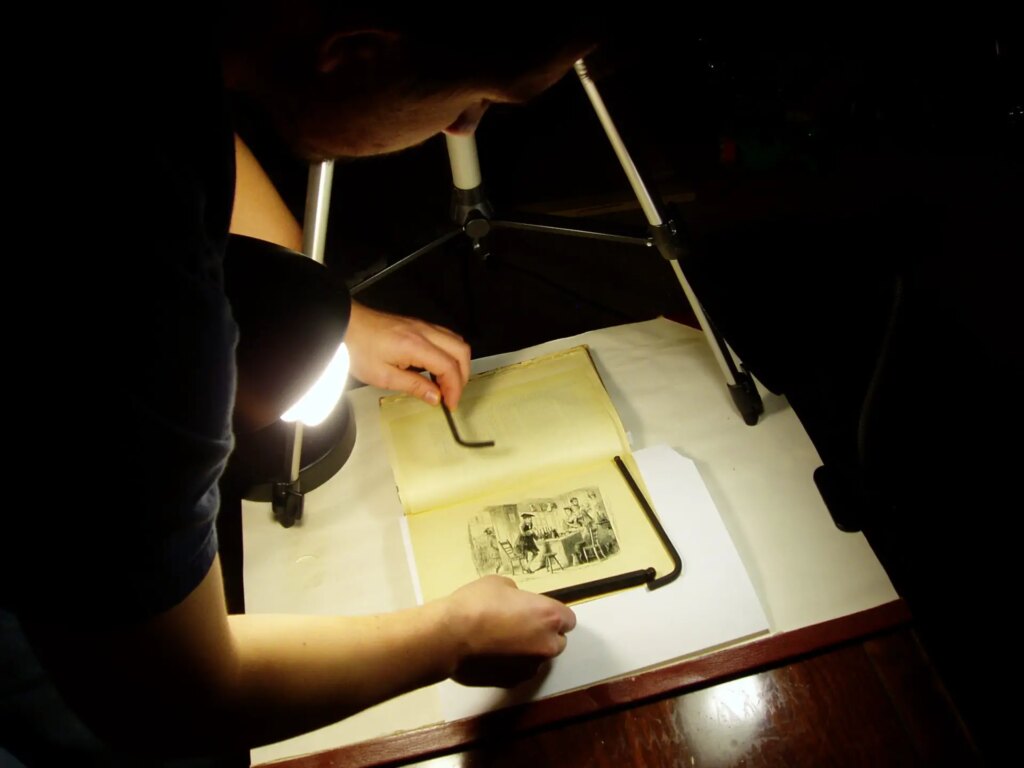

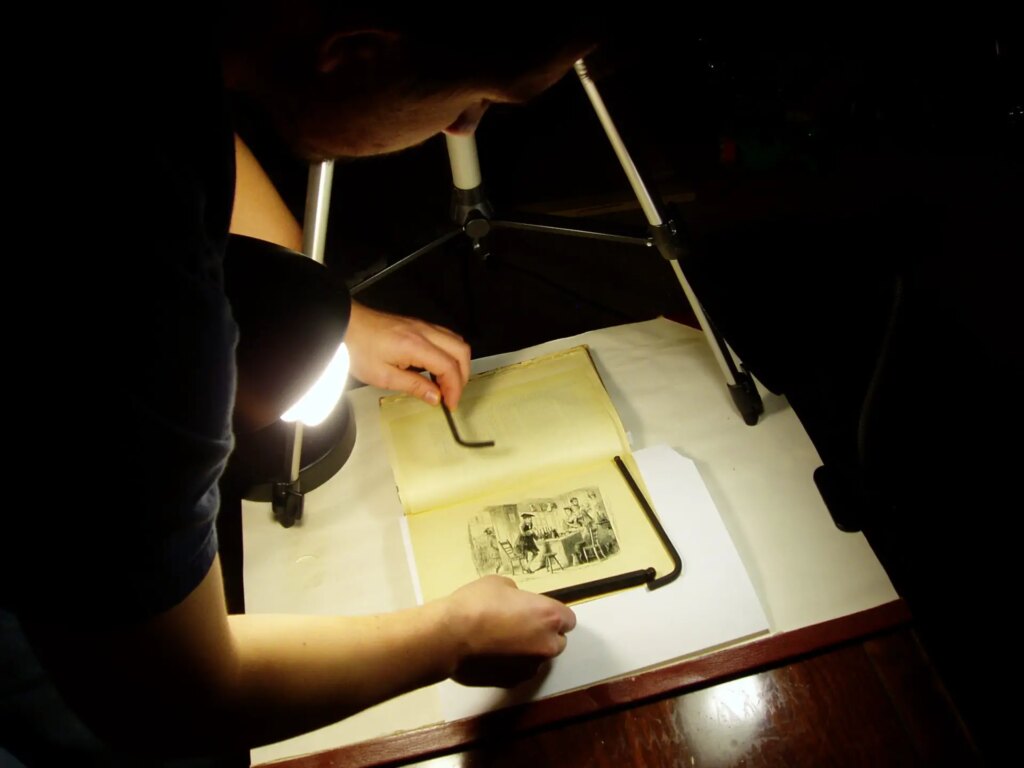

There have been frequent mentions on this website about scans of negatives, ranging from professional labs to table-top models. I’m going to describe my experiences using a loca...

While there is much interest in scanning with a digital camera, there are other ways of scanning negatives: using a lab or home-scanning with a dedicated scanner. Scanning with ...

Whenever we use a camera to record a scene, we are transforming analog signals. Each element introduces yet another error, albeit small.

The perfect is the enemy of the good

...

What is the future of scanning at home going to look like? We will explore the future of home scanning thoroughly by looking at the history of film scanning, discussing how scan...