A recent article by Tom Warland caught my eye, as it very succinctly offered thoughts from a perspective that to me seems to stand opposed to the conclusions I arrived at in my own philosophy, and does so in such a way that makes my response quite straightforward. It is a topic I have covered many times in various ways, but in short: words are not reality.

The presented thesis, as I understand it (and disagree with), is as follows: words shape our relationships, and that a relationship with words associated with photography may be shaped by the relationship those words have to colonial, extractive, or violent activities, such as shooting a gun, capturing, and taking. One who shoots, captures, and takes must surely be the aggressor, conquering their resource, seeking to dominate and possess.

The solution? To change our language, replace these terms and as such remove or reduce those harmful connotations. Make or create are suggested, and there are plenty of other synonyms we can choose to adopt.

In an article that puts colonial vision at the forefront, he seems to miss an essential meta-narrative aspect to the conversation, namely that these terms “shoot, take, make” and so on are words found in the English language, ie the language spoken by many as a first and second but not the default, not in any way more meaningful or holding more weight as a result of our shared understanding, nor its ties to English colonial history.

It is also ever present in discussions on this topic especially within photography that it misses the point of a photograph itself. A photograph is NOT a word, or words. It does something that words and written/spoken language cannot do, and the reason behind being a photographer rather than a poet is for that effect a photograph provides where a poem, prose, or statistic simply will not. What we are doing, with that slight twitch of our finger to activate the shutter and make a record of light entering our lens, can be given any name, and any relationship with that term is ours on a personal level, again our choice to relate to words in a way that fits for us.

Warland’s critique is of a particular language’s metaphorical/idiomatic pathways, not photography itself. The “colonial vision” he identifies embedded in English, is not present in the wider act of creating an photograph. We can read as much or as little into words and language as we like, but confusing them with reality, or choosing to relate to them in a way that places us on the back foot isn’t exactly ideal.

When I’m working, viewfinder to my eye, absorbed by, flowing with my surroundings, I am not thinking in words. I am not thinking about shooting, capturing, or creating. I’m seeing. Not thinking about seeing, or translating seeing into words (unless I’m doing so deliberately, as I’ve spoken about before as a way to engage with the world on that level), simply seeing, composing, and operating the camera. The outcome of this is a photograph.

Of course not everyone is doing the same thing, some people are working within a framework of language even when trying to be truly present in the moment. Is it worth bringing this idea to a deeper, more universal plane, stepping aside from the trap of English/Anglo centrism and saying something about the nature of words (talking about talking) to help those for whom words are a hangup, something they worry about while operating a device where the sole purpose seems to be escaping from words and language?

In French, one prend (takes) une photo, but also may fait (makes) une photo. The language allows both, with prendre carrying a sense of “seizing a moment” more than “taking possession.” In classic Hindi/Urdu the common phrase is फोटो खींचना / فوٹو کھینچنا (photo khī̃cnā). The verb खींचना / کھینچنا (khī̃cnā) means “to pull” or “to draw” implying effort, like pulling a rope (खींचना), drawing a picture (तस्वीरें खींचना), or perhaps more abstractly a combination of both, such as the idiom “drawing water”.

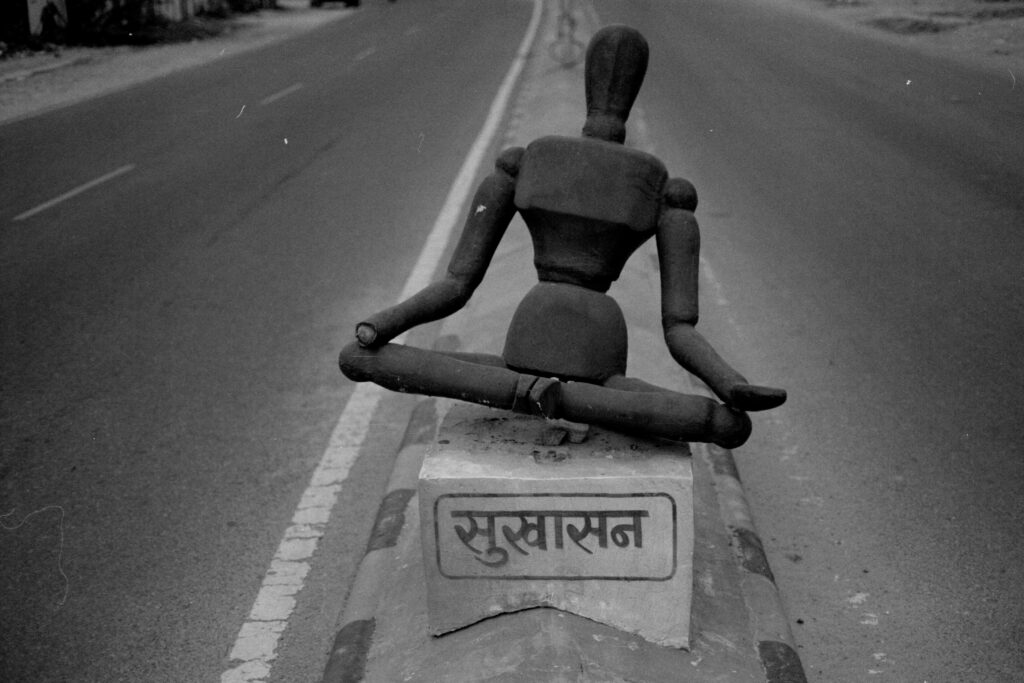

A such photograph is conceptually “drawn out” or “pulled forth” from the scene, a notably creative, almost physical extraction of an image. Having said that, in my travels through Northern India the most common request was for me to “snap” or “click” a photo, which seems their bridge to me and I assume other English speaking travelling photographers they meet.

I very much like the Arabic ألتقط صورة (‘altaqaṭ ṣūrah). The verb إلتقط (‘iltaqaṭa) means “to pick up,” “to pluck,” or “to glean.” Selecting and gathering something that already exists, like fruit from a tree or a shell from a beach, somewhere between “taking” and “collecting” but onto which I project the idea of “harvesting.” When applied to photography “harvesting” works nicely with my sensibility of Objet Trouvé and I do see myself discovering and harvesting the potential in the world around me.

However, one might infer a negative if their association with harvesting is not the rural farmer, set against a backdrop of rolling fields lovingly toiling, tending to the land, collecting the wheat, and instead with the Grim Reaper, camera as scythe, cutting down the souls unlucky enough to find themselves before me… but then that only “works” if you view Death as an evil force, to struggle and battle against, which I do not.

“LORD, WHAT CAN THE HARVEST HOPE FOR, IF NOT FOR THE CARE OF THE REAPER MAN?” ~ Death/Terry Pratchett, Reaper Man, 1991

The photographer is central to their photograph. We curate our lives and surroundings, through our eyes, what we choose to see, what we choose to preserve and share onwards and outwards. The responsibility in my opinion lies in the act, not in the words that congeal around it, freezing us in place like a blocked sink if we choose to give them too much power over us.

Language may have contextual baggage, but only if we choose to carry it. Examples I’ve given before on this topic are that a footballer or basketball player “shoot” their shot at the goal/net, a golfer has a “handicap”, and a photographer photographs a “subject” but these are all metaphor, not truly representative of the act of kicking/throwing, measuring skill, or turning something in the real world into a noun. Semiotics is the study of symbols, which includes words, and reminds us that these layers of metaphor are very much not connected to reality, but fluid ever changing maps not to be confused with the location, menus not to be confused with the food.

While it may be fascinating to look into history and the way our language has evolved, it is also trivial and not to be taken with too much weight, otherwise you end up down the path of numerology, or similar pattern recognition leading to obsession over codes, puzzles, and hidden meanings. Studying etymology should not affect your relationship with base reality.

If someone wants to say they distilled, froze, hit pause, fried photons onto acetate, take a biopsy of reality, whatever metaphor they choose to use is theirs to decide their relationship, and not on someone else to correct or seek to change in order to fit their use of a “problematic” term.

Hopefully I am helping to better contextualise the critique of terminology. Language is a pragmatic, evolving tool. Terms may well fossilise based on functional analogy from a specific era, but that doesn’t freeze the rest of culture in time alongside the word. “Shoot” likely persisted not because photographers consciously embrace violence, but because the mechanical action of releasing a shutter was functionally analogous to releasing a trigger: a simple, memorable metaphor that stuck.

Over time, the primary meaning for photographers becomes the technical act, while the violent connotation becomes a distant echo. Amplifying this echo serves what real purpose in practice? An active push to change how we use words implies that meaning is fixed, and to be avoided if we don’t like it, which to me purges active discourse of history. Is there not a poetry in the way we might capture an image, to recognise that just as we may capture a bird we lose its flight, capturing a moment may have its own melancholic connotation. Is it worth encouraging only one possible interpretation of an idea?

The main insight I’d like to offer is not whether using one word “make” is better than using a different word “take”. It’s the recognition that photography as a practice and craft and result exists in a space between reality and language, and I would say closer to reality than language. Every term is a cultural translation of something that is not itself a word. While articles such as Warland’s may work as a catalyst for an English speaking audience to examine possible “hidden ideologies” within words and phrases, I prefer the wider philosophical principle, that ethical and artistic growth comes from understanding that our tools (words and photographs) are imperfect, clumsy, and exist not only in their own history, culture and context, but as part of the wider fabric of global interaction and discourse.

By stepping away from isolation, by becoming bilingual or better yet multilingual in our metaphors, we free ourselves from the tyranny of a singular narrative, regardless of whether that’s a colonial basis, spiritual, commercial, or anything else.

My advice for anyone struggling with language is not to swap one term for another just because someone else tells you to. Expand your entire conceptual vocabulary. With the humility that comes from knowing that your perspective is not the only one, that there is no hierarchy, no need to mimic, you can choose your metaphors with profound intent, which will help you find your own voice.

Share this post:

Comments

Ibraar Hussain on In Terms of “Terms”, and Giving, Taking, or Harvesting a Photograph

Comment posted: 20/01/2026

And agree - why should we change language and terminology?

As for me I’m NOT a photographer. A photographer isn’t like say, a radiographer or cartographer. Get my cat to tap his paws in the shutter and voila! He’s a ‘photographer’. I think people pompously refer to themselves as ‘photographer’ in the general sense - when they don’t have a camera in their hand

A photographer is much like a driver, or runner, cyclist or anyone who happens to be performing a task or act

Will Wayland wish to examine the colonial of anything and everything? Even the language Urdu which I speak, means Army Camp, and was developed by an Empire to converse with the conquered subjects.

Thanks for the article

Jalan on In Terms of “Terms”, and Giving, Taking, or Harvesting a Photograph

Comment posted: 20/01/2026

Comment posted: 20/01/2026

Comment posted: 20/01/2026

David Hume on In Terms of “Terms”, and Giving, Taking, or Harvesting a Photograph

Comment posted: 20/01/2026

Comment posted: 20/01/2026

Ron on In Terms of “Terms”, and Giving, Taking, or Harvesting a Photograph

Comment posted: 20/01/2026

Art Meripol on In Terms of “Terms”, and Giving, Taking, or Harvesting a Photograph

Comment posted: 20/01/2026

Christopher Welch on In Terms of “Terms”, and Giving, Taking, or Harvesting a Photograph

Comment posted: 20/01/2026

Comment posted: 20/01/2026

Comment posted: 20/01/2026

Gary Paudler on In Terms of “Terms”, and Giving, Taking, or Harvesting a Photograph

Comment posted: 20/01/2026

Gary Smith on In Terms of “Terms”, and Giving, Taking, or Harvesting a Photograph

Comment posted: 20/01/2026

Omar Tibi on In Terms of “Terms”, and Giving, Taking, or Harvesting a Photograph

Comment posted: 20/01/2026

Wishing you a great new year!

Comment posted: 20/01/2026

Tom Warland on In Terms of “Terms”, and Giving, Taking, or Harvesting a Photograph

Comment posted: 21/01/2026

The background to my perspective comes from a series of negative experiences with people outside of photography. I’ve encountered hostility simply for having a camera, even when not photographing anyone. In one instance, accusations were made against me; in another, I was threatened with violence, on the basis that I was apparently doing harm to others merely by holding a camera while crossing the road in Piccadilly Circus. These experiences made me more aware of how photographers may be perceived by the wider public, and prompted a line of thinking about the language we use and the role it may play in shaping those perceptions.

It’s been encouraging to see the discussion develop, and especially to see it culminate in your writing, which clearly demonstrates a high level of consideration. This is particularly appreciated given that, in some comment sections, it’s been suggested that I’ve dictated rather than discussed. Thank you for engaging so thoughtfully — and for not being one of those voices.

Comment posted: 21/01/2026

John F on In Terms of “Terms”, and Giving, Taking, or Harvesting a Photograph

Comment posted: 21/01/2026

It goes back to the classic Sapir-Whorf question of whether language informs thought, or thought informs language. You can say yes to both, but outside of specific complaints from particular communities, Warland's hypothesis seems to stray too far into self-censoriousness, which in my opinion can have a rather deleterious effect on creativity, expression, and freedom.

Rollin Banderob on In Terms of “Terms”, and Giving, Taking, or Harvesting a Photograph

Comment posted: 22/01/2026