In 2013, Impossible Project first teased — and then actually delivered — a miracle device: the Instant Lab, which printed onto Polaroid film. Reviews and press coverage savored the new possibility of turning digital shots into “real” prints, and in that very format: a square 79×79 mm image with its asymmetric frame (narrow on the sides and top, a little wider at the bottom, where you could even scribble a note in small handwriting).

Lost in the noise was the obvious question: why? Printing a square picture with margins and cutting it to the right frame isn’t that hard after all.

But imitation alone wasn’t enough. Nuances mattered. Or something else was bubbling under the surface — unspoken, unadmitted, but piling up.

By accident or calculation, Impossible struck a nerve. Something shameful, perhaps. Something improper to voice. But something desperate to break out.

Impossible were busy reviving Polaroid film, which hadn’t survived the digital revolution, releasing their first experimental batch back in 2010 — the very same year Instagram appeared.

Two worlds, yet strangely aligned if you look closer.

The app’s very name — basically, “image of the moment” — was a wink at instant photography (complete with the camera silhouette icon, rainbow stripe tucked in the corner). Square frames with captions underneath: homage, plain and simple. Retro-washed filters. And its explosive popularity screamed that people were sick of “quality photography” — they wanted something else, at least an imitation. Defects and flaws were no longer guilty pleasures of forum-dwellers; Instagram filters were mainstreaming the aesthetic.

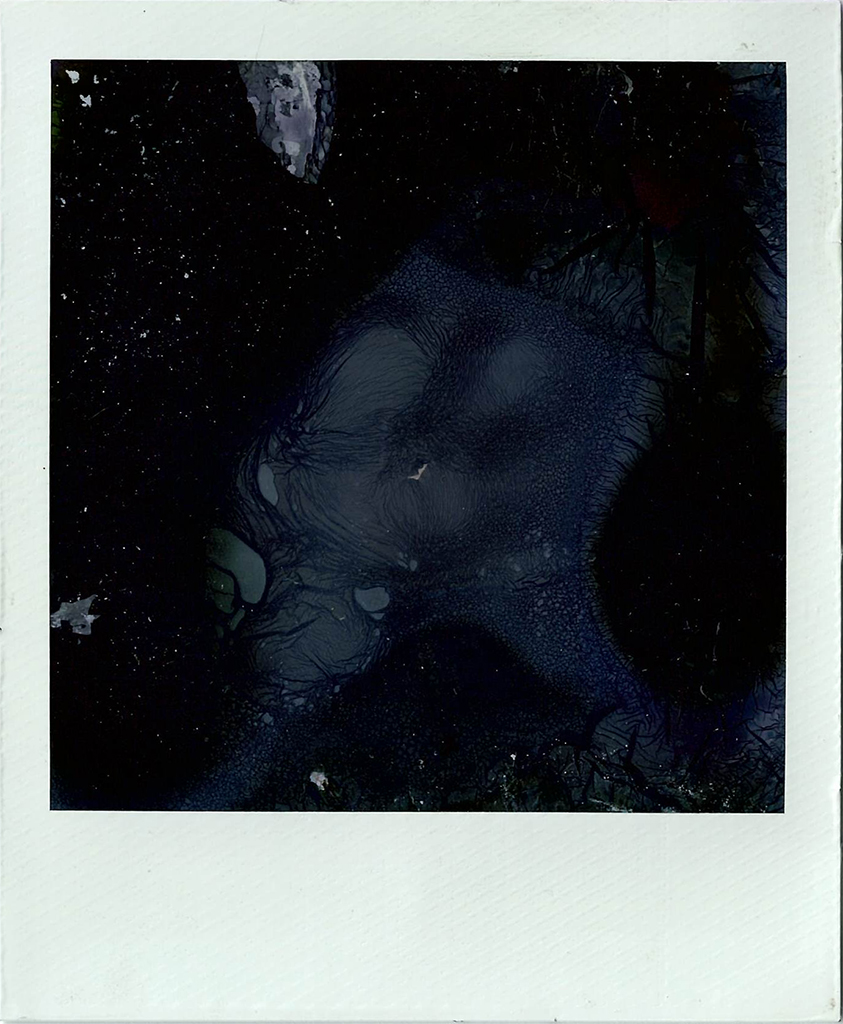

Impossible’s first films had to be reinvented from scratch (the original Polaroid formula was long gone) — reverse-engineering, blind experiments, chaos. The lousy quality was supposed to be tolerated as “temporary,” or reframed as a “feature, not a bug.” The emulsion was literally alive. Experiments rolled on; the lineup expanded. A niche audience embraced it: lomographers, lo-fi fanatics, tinkerers, lovers of grain and expired stock. Those, for whom photography is a process, a game: frame the image that conveys your feeling of the moment in the viewfinder and capture it.

And here’s the thing: for some, choosing a filter may be an agony, but don’t you dare call that creativity.

Lomographers — they’re the glorious madmen, consciously pushing their gear and materials to the edge, heretical souls defying dogma.

Instagram users — sorry — malingerers, simulating life itself.

Polaroid, though, in photography?

A category of its own. Always was.

Press the button, the camera will spit out the print and you watch the image materialize from the veil. A miracle you set loose and which no longer belongs to you.

Unpredictable, elusive, fading, mutating into ugliness.

One single photograph.

Barely scannable, impossible to reproduce — the plastic glare mocks the hardware.

A strange half-brother to daguerreotypes and tintypes. A crooked little bridge back into the 19th century.

And yet: making that one great Polaroid shot, catching that instant, is brutally hard. Hardware flaws plus a laughably narrow exposure latitude — blink, and you’ve lost it. Bought yourself a big cheap 600-series plastic brick? Congratulations — you haven’t bought a camera; you’ve signed up for a lifetime film subscription. A timeshare you’ll never escape. Failed photos will remain splintered in memory, an ache you can’t even quite express. Like dropping a coin in a slot machine when you were a kid — and nothing.

Just a fading scrap of plastic: something-has-been. No matter what — as details blur and outlines fade, it will substitute the real memory: it’s been like that. Enjoy the aesthetic!

Polaroid was doomed. And let’s stop pretending: polaroids are crap.

Instant Lab became an impossible idea: not an experiment, not photography – but reproduction — a forgery, a cheat against the medium itself. Shameful and subterranean, like teenage complexes: the spoiled digital era user’s urge to smash the stubborn material and bend the process to their will.

Like inventing a time machine, going back thirty years, beating up your bullies, and then kissing the girl you were obsessed with (better yet, several of them).

Who am I trying to fool here? Hell no, draining that bloody one-armed bandit dry, of course!

Rewind, repeat, until it stops hurting. Will it?

The Instant Lab should never have existed — the idea itself corroded the medium and the practice.

Impossible must have suspected this, and left a loophole: the device could be dismantled and used as a camera back. Finally, the missing tool. The results were impressive.

And what came after? The team bought the Polaroid trademark itself. The deal price was never disclosed, but surely it was far higher than the old 2008 bargain for the factory. But what are walls and machines compared to a brand legend you can milk forever?

The “new” Polaroid rolled out cameras — stylish, hip, youth-bait. Still useless for thoughtful work. Why bother, when you can sit on every chair generously laid out by pop culture? Shoutout to the collabs with MoMA, Lego, Thrasher!

The device’s support? Dropped. Instead, they flog the Polaroid Lab — another printer, this time sealed tight, no way to hack it into something real.

A change in the name – and such a blatant difference in perception. Impossible Project were dreamers, doubters, probing the edge of the possible.

Today’s Polaroid? A bunch of accountants in lab coats, clipping coupons off nostalgia and vintage chic, while the revived medium they have inherited suffocates.

A false dichotomy, of course: they’re the virtually the same people.

The Instant Lab’s on my desk, mint condition, still working. The fridge hums, hiding a few packs of film inside. The first experiments disappointed me and I sit there, dazed, wondering whether to go on. I could get my pleasure with a bit of persistence and manipulation, but is that instant convulsion of my ego’s delight worth the abuse? I honestly do not know.

Maybe, it’s really better to turn it into a camera? There are some manuals online.

Polaroid. Originals? Impossible!

Share this post:

Comments

Christopher Welch on The Immediate, the Medium, the Media & the Median.

Comment posted: 22/12/2025

brad s sprinkle on The Immediate, the Medium, the Media & the Median.

Comment posted: 23/12/2025

I just purchased a Polaroid Now+ and 5 packs of I-type film for my son. I wish I could be around on Christmas morning to see the face of my grandchild when the first photo pops out and he witnesses a Christmas miracle.

So looking forward to those crappy Polaroids!

Comment posted: 23/12/2025

Alexander Seidler on The Immediate, the Medium, the Media & the Median.

Comment posted: 23/12/2025

Very good written, Thanks !

Niall Keohane on The Immediate, the Medium, the Media & the Median.

Comment posted: 11/01/2026