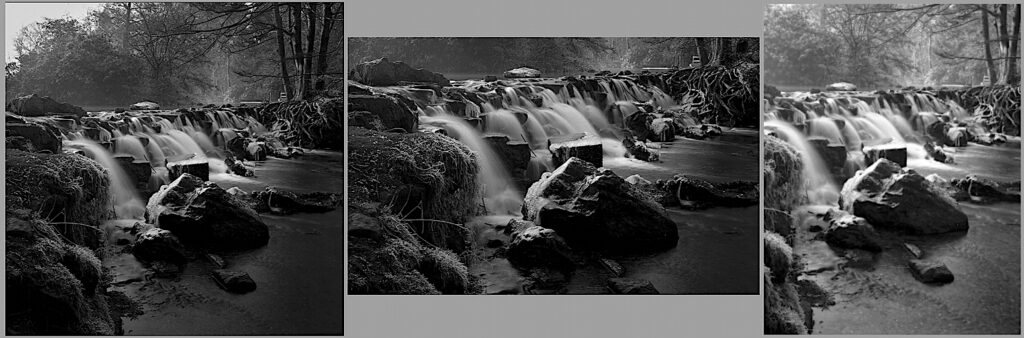

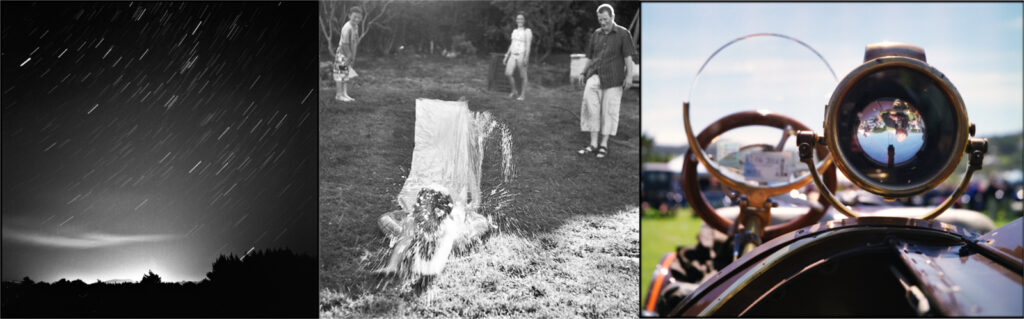

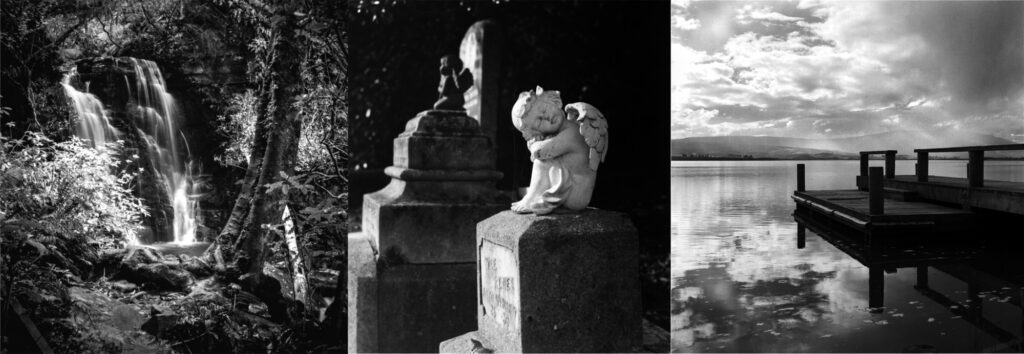

Using a camera now for around 70 years or more I have relied on a twin lens reflex (TLR) of one sort or another for about half of that time. It is one of the most practical and easy to use cameras of all time for me and my kind of photography, a subject I wrote about briefly some years ago. So I will present here something about the type and my experiences of using several versions, like standing in front of the class again.

There is something very satisfying about seeing an image come into focus on a ground glass at waist level in a TLR finder. With a TLR you also have to deal with a laterally reversed image, i.e. right is left and vice versa for panning, framing and composing the image. Mind you, I was always told to judge a print upside down or in a mirror to decide the final crop. Having to consider an image that is reversed in some way seems to force a more objective assessment, so a TLR could be said to improve your photography as well as all its other plusses!

History and design

The basic design of a reflex camera with a 45° mirror to allow focussing on a ground glass screen, has persisted from the late 19th century. A German firm, Krügener, produced a rudimentary falling plate camera with twinned lenses and a ground glass screen with a hood around 1890 but only the taking lens focussed. Still, the finder must have been better than the more usual, small, brilliant type. Those early examples took plates or sheet film and were very bulky instruments.

The stereo camera’s method of mounting two matched lenses on a common panel for focus was also well known around 1900 and earlier. But it wasn’t until the late 1920s that two gentlemen in Germany, Herren Franke und Heidecke, brought all these things together in their Rolleiflex camera, which introduced its now familiar and much copied design.

The stereo cameras Franke and Heidecke (F&H) were producing in the 1920s, the Rolleidoscop and Heidoscop, and the very similar 1914 Voigtländer Stereflecktoskop (no “o”) show a close resemblance to the eventual Rolleiflex design. It seems no coincidence that F&H met at Voigtländer before the first world war. Both makers cameras had a reflex viewfinder with hood and magnifier for focus and framing coupled to two linked lens/shutter units placed either side of the central viewfinder lens. The F&H version also had a second eye-piece and mirror for focussing and viewing at eye-level similar to the later Rolleiflex hood whilst the Voigtländer had a simple frame finder for eye-level viewing. With minor re-configuring, all the main design elements of the TLR can be seen in these stereo cameras.

It is quite remarkable that the basic Rollei design concept changed so little throughout its life, from 1929 to the 1980s and later. The only essential difference between the first Rollei TLR and the last was the addition of an exposure meter. Only the technology improved and the lens and shutter of the earliest example were no match for those used on the later models. Nevertheless, anyone can pick up a TLR and will almost immediately be comfortable with its basic operation. The viewfinder is one of the easiest to use, whilst the square format means there is no need to contort yourself to change from landscape to portrait as you shoot, cropping the print later in the darkroom or simply printing in the square format.

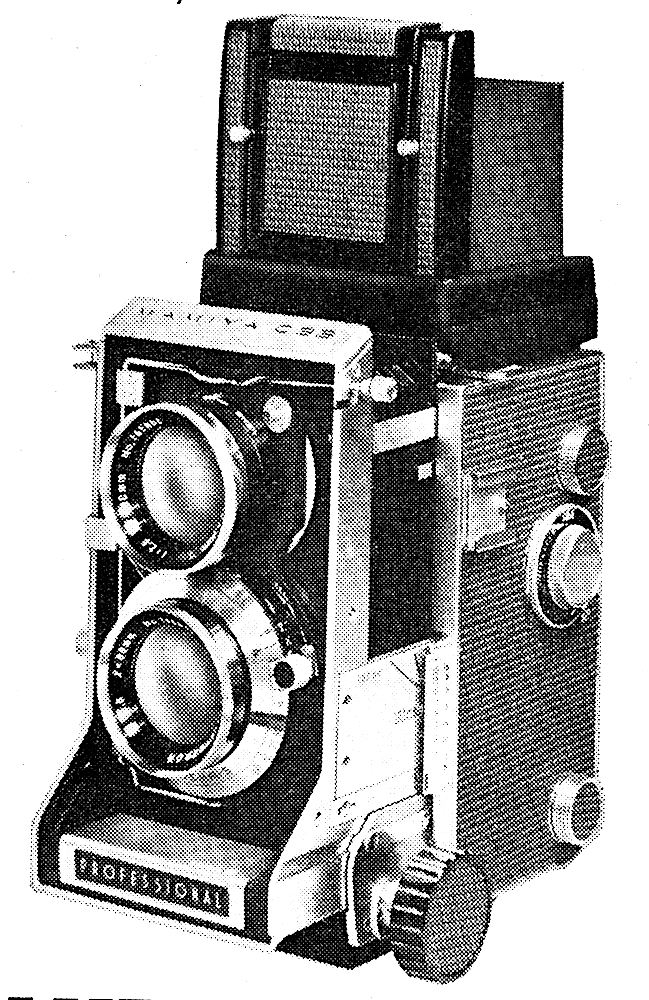

The design has been copied many times by different manufacturers, from the basic Voigländer Brilliants and Kodak Brownie Reflex types of snapshot camera to the extremely developed Mamiya C330S system. I have personally used a Microflex from the UK, a Yashicamat, Autocord and Mamiyaflex from Japan, Flexaret IV and V from Czechoslovakia and a Rolleiflex from Germany. Other version were made in China, France, Russia and the USA that I am aware of using the basic Rollei configuration.

Rather than having the lenses mounted on a common panel which was moved to focus, some simpler models used gearing between the two lenses in order to synchronise the focussing movement.The Gowlandflex took it further and was used by glamour and celebrity photographer Peter Gowland for use with 5×4 film. A 10×8 version was also produced according to Camera-wiki.org.

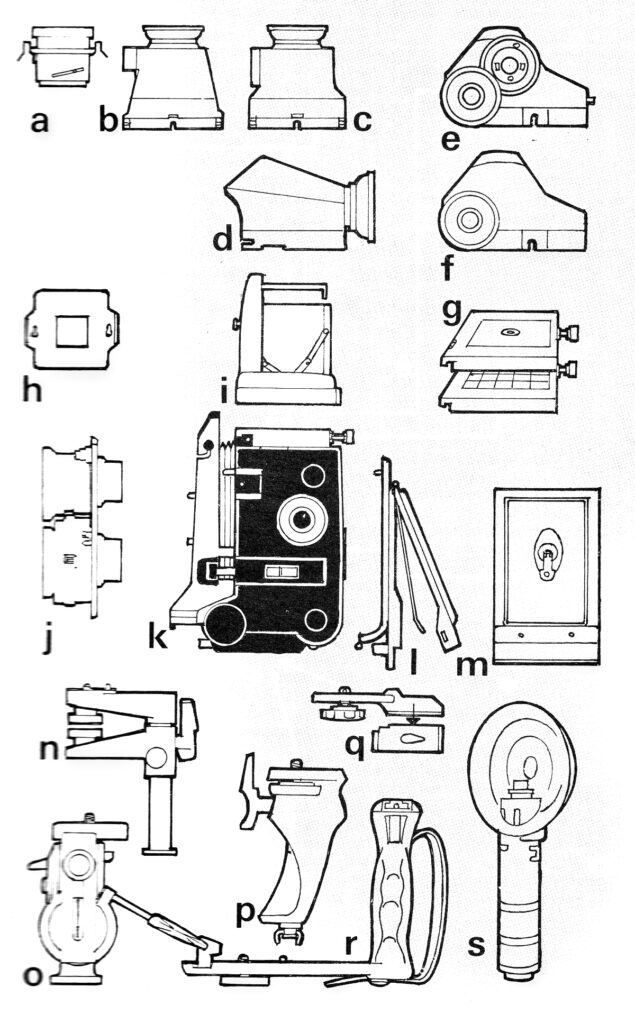

The model of TLR I used for the longest time was a Mamiya C33 with 55mm and 105mm lenses, the only commercially successful, interchangeable lens TLR. McKeown’s lists a Voigtländer prototype from the 1950s but it was never put it into production. Mamiya developed its C series into a very comprehensive system and provided some really excellent Sekor lenses to accompany it. The system included interchangeable backs, screens and finders as well as a range of seven lenses from 55mm to 250mm. Bellows focussing also allowed much closer focus than normally available on this type of camera. An indication of parallax error is visible in the finder with a bar that descends from the top of the frame as focus is brought closer to indicate the top of the image. When supported by the simple Paramender accessory the tripod mounted camera was lifted after focussing to bring the taking lens into the position that had been occupied by the viewing lens. Rollei, on the other hand, solved the parallax problem optically with a finder lens attachment that deflected the image downwards through a prism to match the taking lens producing accuracy at the subject plane but with a displaced background. The Paramender ensured the background was accurately reproduced to match the finder image but could really only be used with static subjects.

Handling

Probably the best feature of the TLR type camera is that the way the camera is held does not need to change between landscape and portrait, being a square format. But the layout of focus, wind-on and release of many models of the Rollei range impose the annoying need to shuffle the camera hand to hand between exposures in order to wind on other than with some Rolleicord models. Many of their imitators persisted with the same arrangement but quite a few did something about it, notably Meopta’s Flexaret and Minolta’s Autocord. The Flexaret V focus is controlled by a lever below and concentric with the lens which allows the left hand to support the camera and focus, whilst the right hand releases the shutter and winds on without having to change grip. The Autocord is similar but the shutter release falls under the left hand also leaving only the wind on for the right hand to deal with or to focus if preferred.

The Kalloflex’s possibly ideal solution was to place the wind lever and focus concentrically on a common hub so that the right hand focusses the lenses and also operates the wind on lever, the left hand supporting the camera and releasing the shutter. Its successor model the Kallovex dropped this arrangement, however.

Mamiya’s arrangement of two focus knobs allowed focus to be operated from either side of the camera and overcame the handling problem neatly if not as elegantly as Kowa. Wind on and shutter release are both on the right hand side so everything can be done with the right hand if needed with the left hand only needed to support this rather heavy camera.

My TLRs

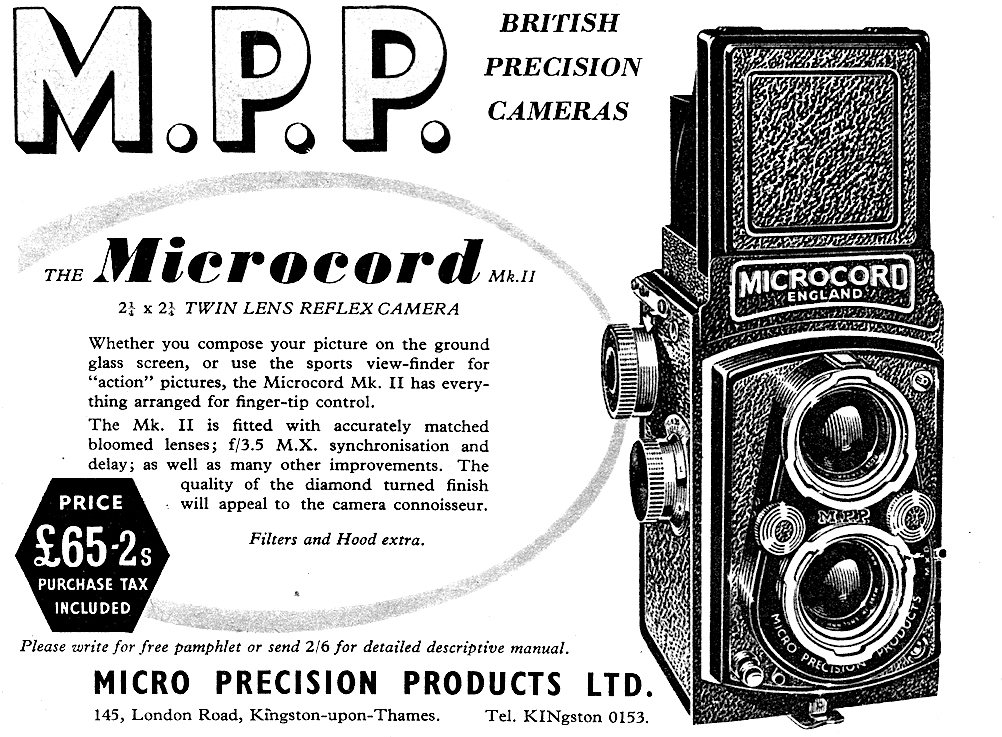

MPP Microflex

This was my first TLR, a copy of the Rolleiflex made in the UK for just two years between 1958 and 1960 until removal of UK post-war import restriction made them uncompetitive with imported versions. MPP made press and technical cameras for large format so this and the Microcord, a Rolleicord clone, was quite a departure. It was of the best quality both optically and mechanically, the 77.5mm f3.5 lens being designed specifically for this camera by Taylor, Taylor & Hobson, set in a Prontor SVS shutter. Camera Wiki states that it had a quirky film load system, but I don’t remember having any problems with it. Apparently it is necessary to load a new film before closing the back after removal of the previous film. Probably mine was never empty in those days as it went almost everywhere with me and produced some great results. I also won my first magazine prize with it, the princely sum of 10/- or 50p these days, in a Photo News Weekly competition.

Yashicamat

I don’t have a photo of my Yashicamat but it is very similar to all the ‘Flex clones.

My next TLR was a Yashicamat from around 1960 and was an almost exact copy of the Rolleiflex Automat apart from the second eye-level viewfinder incorporated into the hood. The larger negs compared to 35mm allowed much greater degrees of enlargement and cropping when necessary, making up for the fixed lens to some extent. Again, it went almost everywhere with me and made some excellent images with the Tessar type, 4-element Yashinon lens in 10 speed Copal MXV shutter. A very well made camera and one I used for quite a while, despite the hand to hand shuffle between exposures.

Mamiya C33

I bought the C33 in the 1960s. It had had quite a hard life by the time I bought it but apart from a stripped gear in the 105 shutter it never missed a beat for several years. A moderate wide angle option was the main attraction for me for architectural work. The f3.5 105mm lens was very sharp and gave slightly better perspective than the 80mm, and the 55mm wide angle was equally good but a bit dim at f4.5 maximum aperture. Using it in relation to my work as an architect, the camera was normally tripod mounted so focussing didn’t need to be lighting fast. The loan of a friend’s impressively sharp 250mm lens was a revelation, both in sharpness and composition, so that I was reluctant to return it. I added a Porroflex eye-level reflex finder to the kit, much lighter than a pentaprism, using mirrors to correct the finder image but as a result not as bright though still a very useful accessory.

Rolleiflex Automat MX

Again, no photo but, like the Yashica, very typical of the type.

Towards 2000 digital cameras were rapidly taking over from film and for around 10 years I was seduced by their novelty but then I gradually gravitated back towards film. A Rolleiflex Automat MX from the 1950s was my first post-digital acquisition with a Tessar lens and Compur shutter. It was not mint but worked well. The arrangement for focussing at eye level as well as the frame finder as mentioned above were very useful features. Film loading was completely automatic, the film being fed under a feeler bar which set the counter and frame spacing when the film itself passed underneath. I also built up a collection of filters, close up lenses and lens hood in bayonet 1 fit which proved a good investment, fitting my subsequent Autocord acquisition. Again, however, the shuffling hand to hand niggled me and I soon sold the camera on.

Meopta Flexaret V

This was my favourite camera from a handling point of view. Supporting the camera and focussing with the left hand and releasing the shutter with the same hand as winding on made for the smoothest operation along with the C33. The weight difference between the two was significant though. The camera, made in the late 1950s, was a very clean example and worked flawlessly, the f/3.5 80mm Belar lens producing sharp images mounted in a Prontor SVS light value shutter which was accurate and very positive in use.

Minolta Autocord LMX

Along with the Flexaret, the Autocord handles very well. The example I had was very clean and also worked perfectly. It was the LMX model from the late 1950s and incorporated a photoelectric exposure meter which also worked well even after 60 years or so.

The meter’s operation is unusual in that it works on a system of light values that takes a little getting used to but very practical once you have. The meter is set to the film speed in use and gives a reading of a single light value. The shutter and aperture levers operate against numerical scales around the lens and the idea is to set them so that added together they match the value given by the meter. For example, if the meter reads 10, then an aperture value of 4 and a shutter speed value of 6 would give the correct exposure. Alternatively aperture or speed could be preset, selecting its partner to match the meter reading. Actual values appear in windows above the finder lens as with most other types to check the settings in conventional fractions of a second and f stop values.

One thing to watch with this camera is the focus lever. Apparently, Minolta used quite a brittle metal for this component and, if the focus becomes stiff through lack of use and/or dried out lubricants, it can simply snap off. Fortunately the focus on my example was as smooth as when new and had probably been serviced at some time.

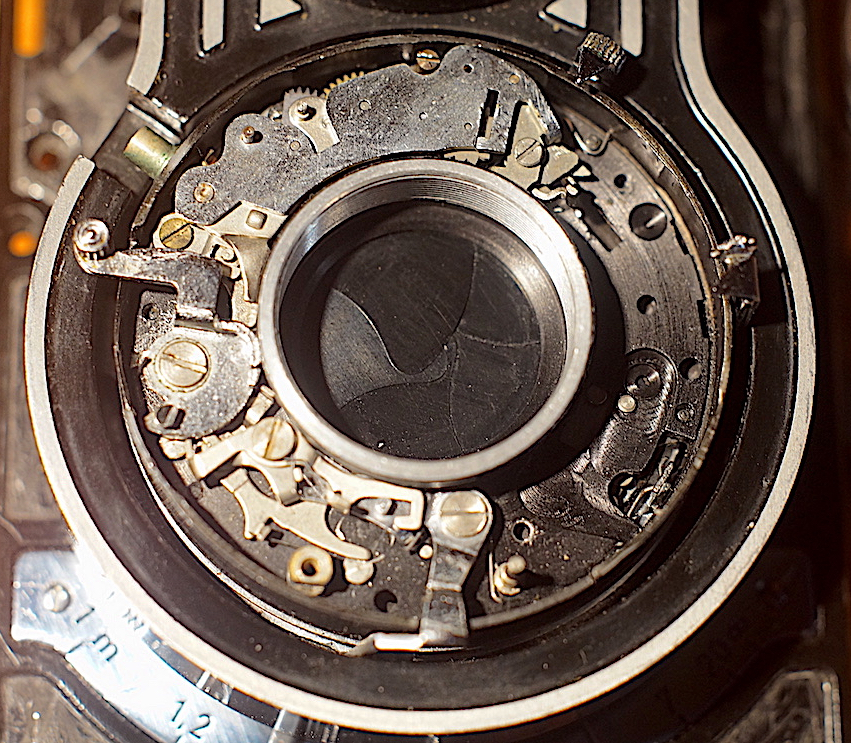

Meopta Flexaret IV

Selling my cameras on as I have done in recent years, means that I often think back fondly on the ones I have let go. I began to feel the absence of a TLR in my life some time after selling the Autocord and so I purchased a Flexaret IV. It had some obvious problems from the photos but I decided to take a chance only to find several more. Anyway, to cut a long story short, after a thorough overhaul it produced some good results even though it was missing the complete delayed action (DA) pallette from the shutter mechanism, meaning no flash sync or DA, and possessing the largest bubble in the taking lens that I have ever come across.

Compared to the model V I had previously, the IV is more basic, with manual shutter cocking and no click stops on the shutter speed ring. From the serial number it was made in the first year of the Prontor SVS shutter’s production. In the following years several modifications were made to this shutter and parts are not interchangeable and difficult to find.

In Conclusion

Of all the cameras types I have used the TLR is the standout as a practical, portable and versatile instrument. Granted, it cannot match 5×4 for out and out detail, or the wide range of focal lengths 35mm and medium format SLRs can offer. It doesn’t slip in the pocket in the way my Olympus XA did but as a take anywhere, tackle most things camera it takes some beating in my book. I often think back fondly to my many years with this type of camera.

Certainly, if you want to dip your toe into medium format film, a TLR could be a very good starting point.

Share this post:

Comments

Thomas Eland on Twin Lens Reflex – My Experiences and Thoughts on this Camera Type – Show and Tell

Comment posted: 29/09/2025

It never ends

Comment posted: 29/09/2025

Gary Smith on Twin Lens Reflex – My Experiences and Thoughts on this Camera Type – Show and Tell

Comment posted: 29/09/2025

Comment posted: 29/09/2025

Comment posted: 29/09/2025

Comment posted: 29/09/2025

Comment posted: 29/09/2025

Stefan Wilde on Twin Lens Reflex – My Experiences and Thoughts on this Camera Type – Show and Tell

Comment posted: 29/09/2025

an interesting in depth look at your TLR journey with great images to go along with it! I call a couple of TLRs my own. I just got a Seagull 4a practically for free and was pretty impressed what it could deliver!

The one thing I'm not quite getting is your issue with shuffling hand to hand. Do you use your TLRs handheld without a strap? In that case I see how it may be awkward. I use my Rolleiflex with a strap, as I consider it essential for the design to work. I find it very smooth fuss free to operate. What are your thoughts, am I overlooking something?

Cheers

Stefan

Comment posted: 29/09/2025

Geoff Chaplin on Twin Lens Reflex – My Experiences and Thoughts on this Camera Type – Show and Tell

Comment posted: 29/09/2025

Comment posted: 29/09/2025

Stephen R. Kruft on Twin Lens Reflex – My Experiences and Thoughts on this Camera Type – Show and Tell

Comment posted: 30/09/2025

Comment posted: 30/09/2025

Alexander Seidler on Twin Lens Reflex – My Experiences and Thoughts on this Camera Type – Show and Tell

Comment posted: 30/09/2025

Comment posted: 30/09/2025

auntimaryscanary on Twin Lens Reflex – My Experiences and Thoughts on this Camera Type – Show and Tell

Comment posted: 30/09/2025

For TLR's I started with a Lubitel 2 that I never gelled with and sold it 2 or 3 years ago, broken, for £2! (Although it did live again after the purchaser repaired it). By then I'd purchased a Mamiya C3 and it continues to be my go to camera.

I thought I'd try a further, and considerably lighter, TLR so purchased a Meopta Flexaret IV. However it's only had a couple of films through it as it doesn't focus correctly. I should get the Flexaret serviced really but the C3 does everything I want in a TLR so the Flexaret remains neglected. I'm on the look out for a Mamiya Paramender, not that I need one, but quite fancy the ability to do close ups with the C3 especially as it has a minimum focus of 30cm (12") I believe.

Comment posted: 30/09/2025

Ibraar Hussain on Twin Lens Reflex – My Experiences and Thoughts on this Camera Type – Show and Tell

Comment posted: 02/10/2025

By the way have you seen Martin hensons latest review of a Seagull TLR? https://youtu.be/jv1g9HPyCkw?si=dehfNzjaH-JAJ0vX

Comment posted: 02/10/2025

Jeffery Luhn on Twin Lens Reflex – My Experiences and Thoughts on this Camera Type – Show and Tell

Comment posted: 02/10/2025

What a remarkable article about the history and results from so many TLR cameras! Great photos!

I have many vintage cameras including several Zeiss folders, 120 SLRs, a Mamiya C33 w/3 lens sets, and two refurbished Rolleicords. I cycle through all my cameras so they get fresh air, sunshine, and fresh film. It's the Rollei cameras that I enjoy the most. Maybe I could sell both Rolleicords and buy a Rolleiflex, but why? Same lens and similar feel. Nothing beats the Tessar on the Rollei cameras. Sharp, sharp, sharp!

Jeffery

Comment posted: 02/10/2025

Art Meripol on Twin Lens Reflex – My Experiences and Thoughts on this Camera Type – Show and Tell

Comment posted: 26/10/2025

Comment posted: 26/10/2025