It’s 2 o’clock and here I am dragging 50 homemade pinholes cameras into Copperwood, Boomtown’s 1920s Hollywood-inspired district. Boomtown is one of the UK’s biggest music festivals with over 70,000 attendees. The gates have just opened and it’s absolutely rammed with people looking for a good time, that’s when I start to wonder; “who here is going to care about my large format camera and pinhole photography?” When I pitched, I was confident: with this year’s festival theme being “The Power of Now”, I focused on the mindful, slow process of capturing an unfolding moment, capturing, “now” mindfully. Now I was standing here, with streams of Gen Z ravers bouncing past, I wasn’t so sure this was a good idea, who could blame them for not caring?

With confidence low, I started my shift, vowing to “give it a go” and already concocting excuses as to why pinhole photography hadn’t been the big hit I’d vowed it would be. I didn’t even have time to set up my pitch before the first ‘citizens’, as Boomtown refers to attendees, started to gather around in interest. I’d been far too quick to judge them. They weren’t just there for the music. They were hungry for wonder, for encounters, for something different. Their joy at the sheer spectacle of it all. The themed streets, the costumed performers, the sense of walking into another world, it was contagious. I suddenly understood the role: not just to take photos, but to add to the magic, to become part of this sprawling artwork.

I reminisced of my first Glastonbury experiences as an eager 17-year-old in the 90s. Some of my best times have been spent dancing with strangers as the sun comes up in fields around the world. I had feared my traditional photography would be an underwhelming disappointment in a festival full of spectacle and wonder. But I was wrong. It turns out there was no need for apprehension. Traditional photography went down an absolute storm.

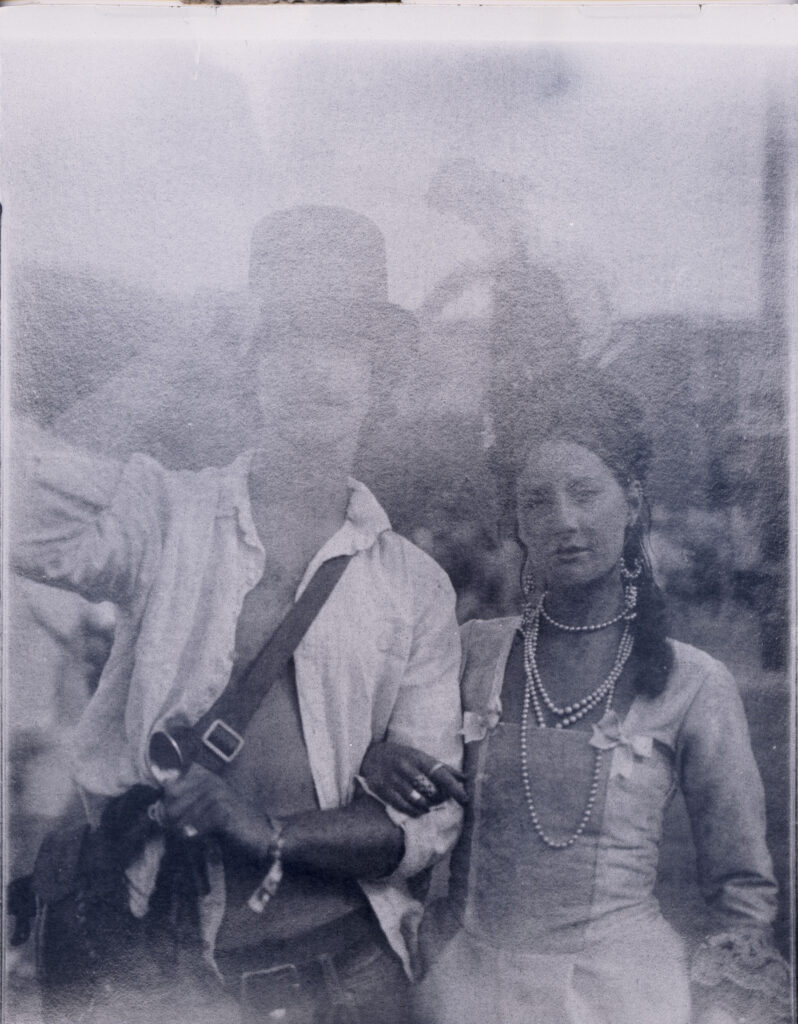

It turns out that by embracing the power of now and capturing a moment in time, savouring it, and making an actual physical relic of it was what people were looking for. In an age where a moment hasn’t happened unless it’s been shared on social media, every long-exposure pinhole that was took was a testament to a shared, present moment. A collaboration in patience between us and the ‘citizen’ of Boomtown who chose to step into this old-school photography world.

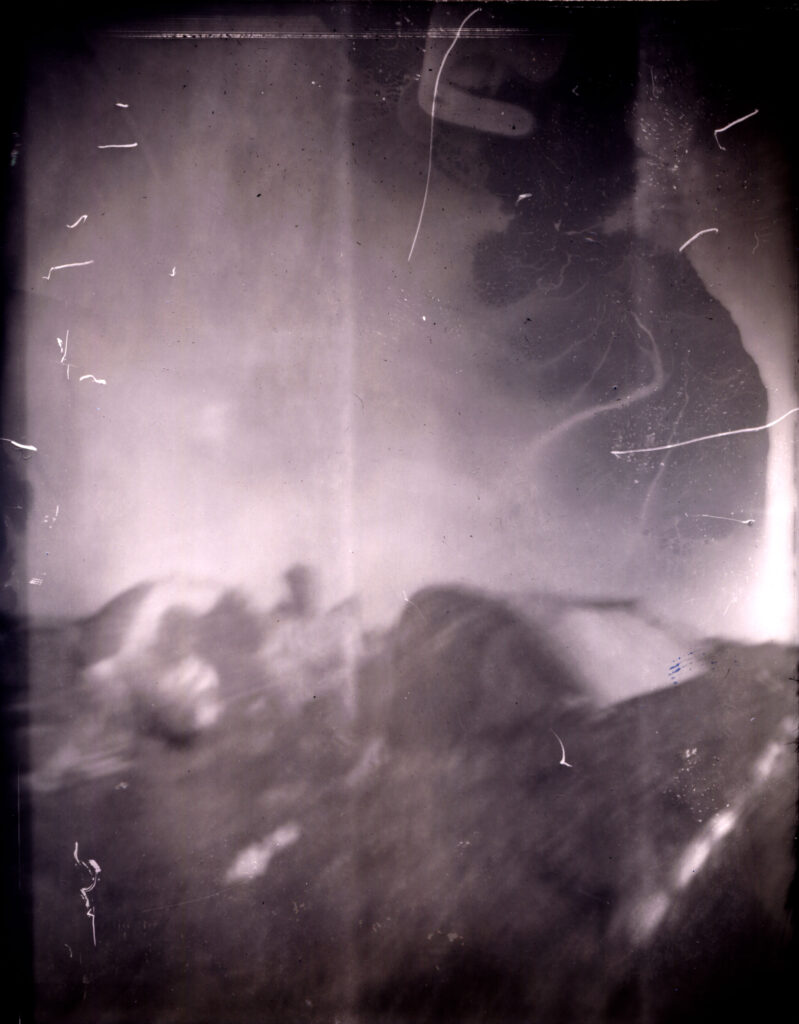

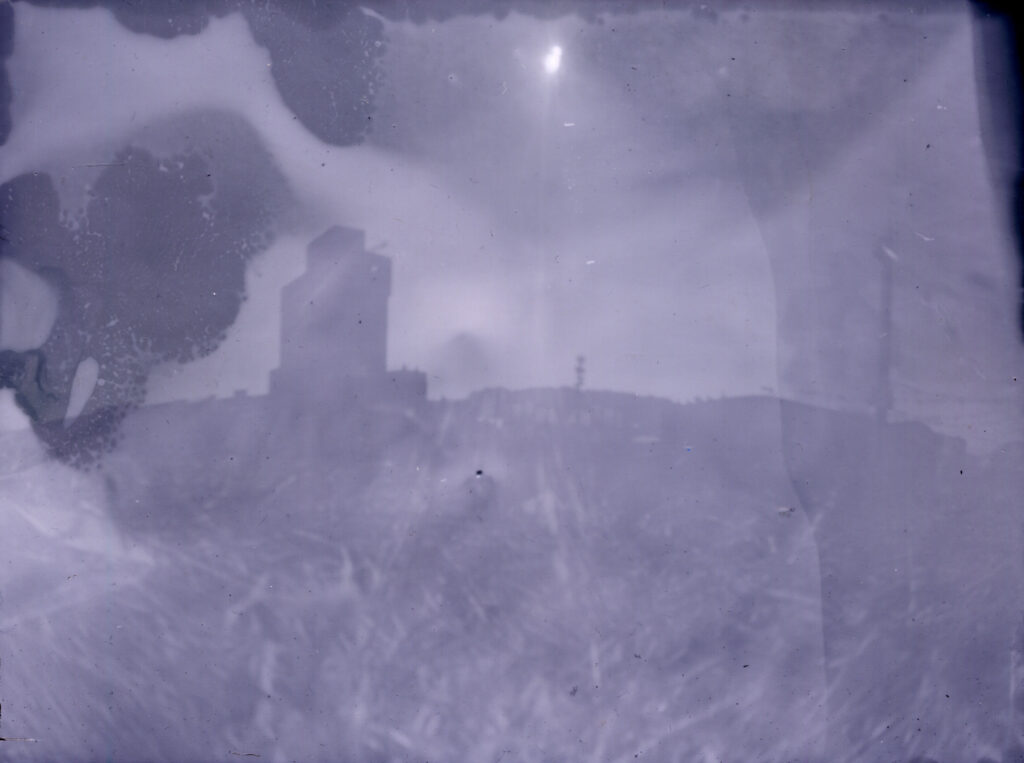

Over three days I handed out over 50 pinhole cameras: tiny cardboard tubes with a pinhole aperture and a piece of light-sensitive paper. No viewfinder, no ego, no instant result. Just a 10 to 30 second exposure and a leap of faith. Watching people use them was fascinating. They slowed down, studied the light and composed on instinct. One young lad turned to his mate, eyes wide: “Bro, we’re capturing photons.” Others returned two days later with their pinhole cameras, confessing how they waited for their perfect moment. In a world of instant hits, this felt radical. Intention over immediacy, artistry over convenience.

Pinhole photography does that to you. It forces you into a gentle stillness. To stand still for 20 seconds in the chaos of a festival field is to experience it differently, to really notice the scene in front of you. In typical Gen Z fashion, the pinhole camera became a tool for unique selfies with them standing still whilst the rest of Boomtown fades into a blur.

What struck me most was how many young people already carried their own film cameras. Some even took portraits of me. Their passion wasn’t retro or ironic. They craved the process and wanted to exchange knowledge. Analogue photography hasn’t disappeared. It’s being rediscovered, and at Boomtown it felt alive, communal, and absolutely authentic.

My most unlikely star was my Lego camera. A 4×5 large-format beast cobbled together from a bag of old eBay Lego bricks, built to be portable and more importantly – droppable. It was part sculpture, part camera, but most importantly it was a conversation-starter. They stopped, they asked questions. This daft camera demystifies the intimidating world of large-format photography and makes portrait-taking playful, collaborative, and much more social.

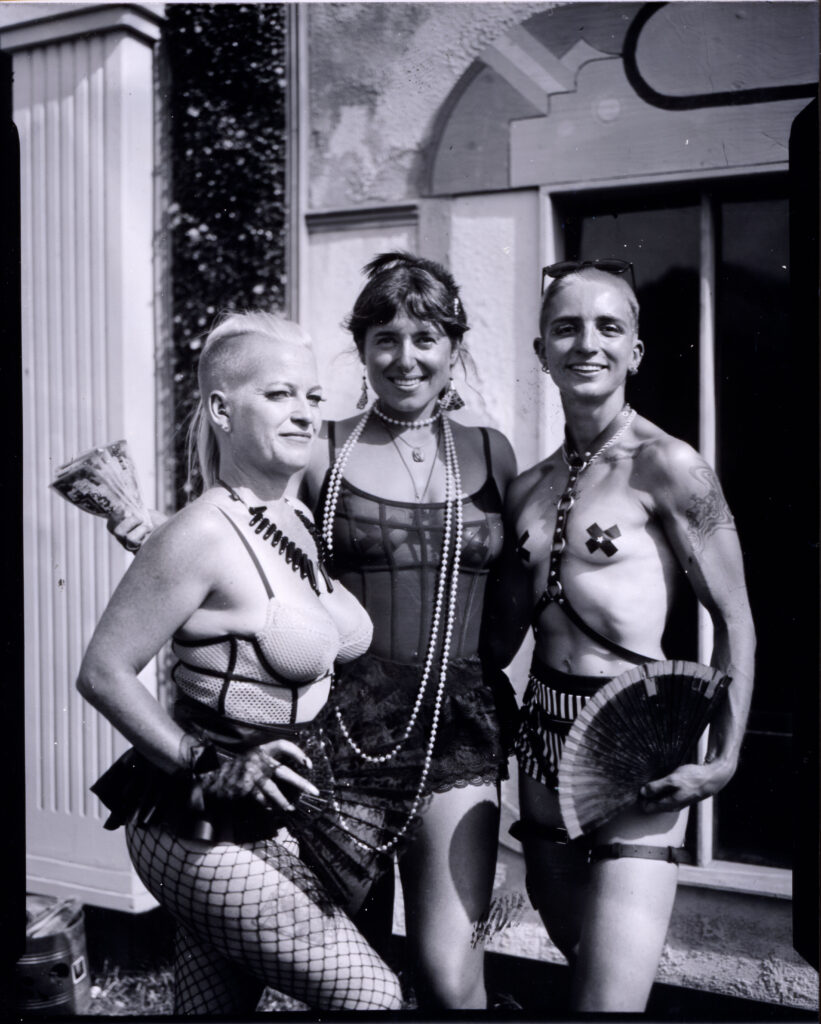

Across three days I shot more than 150 portraits, all on vintage photo papers from Kodak, Ilford, and long-gone brands like Jessops and Orwo, some papers more than 70 years old. Each sheet, with its treacle-like tones and peculiar quirks, gave every portrait an unpredictable individuality.

Behind the scenes too, Boomtown was full of revelations. Working alongside contortionists, samba bands, fire eaters, and theatre mavericks illustrated the incredible breadth of talent that finds a temporary home here. Mornings in the artist camp, with rows of articulated lorries turned into bespoke homes, each adorned with DJ booths or jam spaces gave me a glimpse into the hidden village that powers the spectacle.

I arrived at Boomtown nervous I would be out of place. I left Boomtown with boxes of exposed sheets waiting to be developed, dozens of numbers to send pinhole and portraits to, and a renewed conviction that what we do matters. Traditional photography is far from obsolete. In a culture awash with digital overload and increasing AI slop, the deliberate slowness and tangible imperfection of traditional photography offers something real.

Share this post:

Comments

Dean Lawrence on Booked for Boomtown at Fifty Years Old – Will They Care About Pinhole Photography?

Comment posted: 23/10/2025

A cracking article with some wonderfully captured "moments".

Comment posted: 23/10/2025

Michael Jardine on Booked for Boomtown at Fifty Years Old – Will They Care About Pinhole Photography?

Comment posted: 23/10/2025

I've found that people of any age can't help but go nuts for large-format portraits. I was at a 40th party a couple of years ago and set up a darkroom in a sauna (I knew the venue, and that this space could be easily made light-proof) and did 'instant portraits', with a 4x5 field camera on regular Ilford MG resin-coated paper, with the contact prints made with the wet paper sticking itself together with the paper negative... I'm sure you know the drill! It wasn't quite as instant as I'd hoped as we'd spent the afternoon in the local brewery tap-room (https://briarbank.org/) but people were so thrilled to be made to look like 1900s Australian outlaws!

Comment posted: 23/10/2025

Alan Withington on Booked for Boomtown at Fifty Years Old – Will They Care About Pinhole Photography?

Comment posted: 23/10/2025

Gary Smith on Booked for Boomtown at Fifty Years Old – Will They Care About Pinhole Photography?

Comment posted: 23/10/2025

Interesting gathering.

Thanks for posting.

Adrien Grelet on Booked for Boomtown at Fifty Years Old – Will They Care About Pinhole Photography?

Comment posted: 23/10/2025

Thank you !

Comment posted: 23/10/2025

Jeffery Luhn on Booked for Boomtown at Fifty Years Old – Will They Care About Pinhole Photography?

Comment posted: 25/10/2025

Great writing and photos! Ambitious concept to hand out pinhole cameras! It worked!

Jeffery

Comment posted: 25/10/2025