“The camera is just a light-tight box.”

If you spend time on photography websites and forums, you’ve probably encountered this dictum before – often as an admonition from veterans to newbies who want to know what camera to buy.

I disagree with the “just a light-tight box” theory for a number of reasons. The camera body determines the film format or sensor size, which has a big impact on the image. The size and shape of the body, and even the loudness of the shutter, can influence where and how you use the camera. Automation can make a camera easier to use (though not always).

And then there’s the viewfinder.

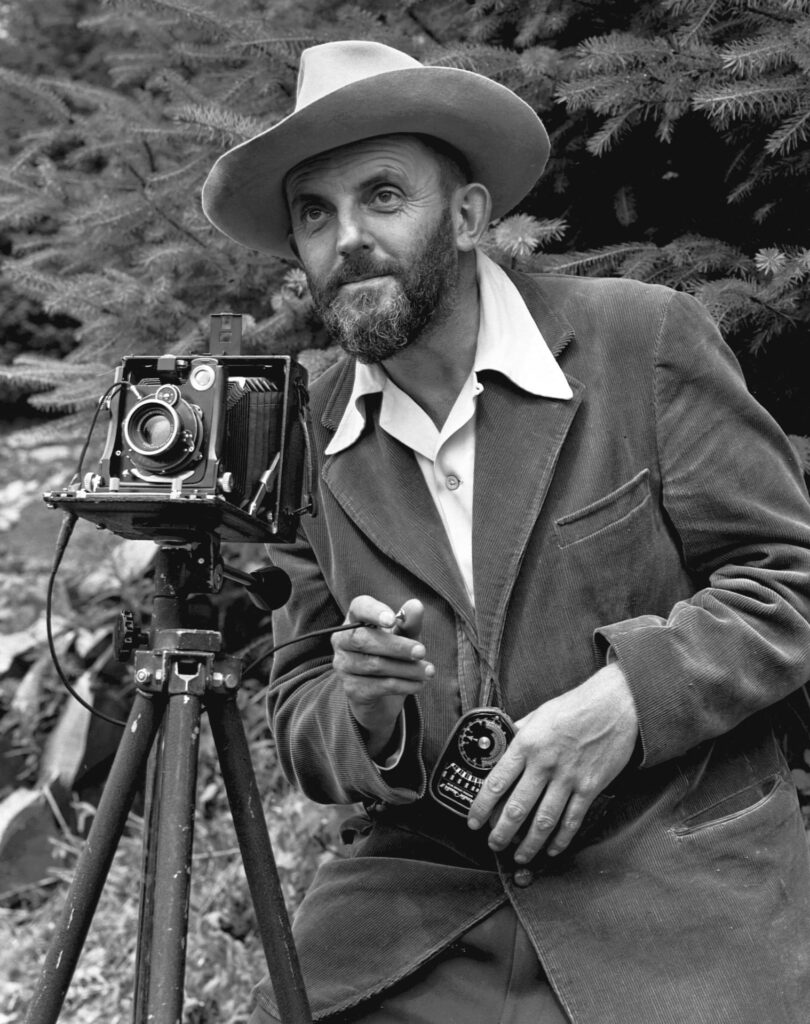

It’s true that the lens – the “taking lens”, to be precise – creates the photographic image, but the viewfinder is the device through which the photographer sees and creates. And as Ansel Adams put it, “The single most important component of a camera is the twelve inches behind it.”

Indeed, the viewfinder is so important that it has “determined and defined most different basic camera types” (the quote is from Mike Johnston’s excellent article about SLR finders). SLRs, TLRs, venerable view cameras, modern mirrorlesses – all these camera-types are literally named after the means by which an image of the scene is delivered up to the photographer’s eye.

Life-like and photo-like finders

There are many ways to classify viewfinders.

One common distinction, especially since the rise of mirrorless cameras, is between optical and electronic finders. Finders can also be classified according to the basic design (SLRs, TLRs, direct optical finders like those found on compact cameras…), the type of focusing aid (split-image, rangefinder, ground glass…) and in various other ways.

For some time now, I’ve been thinking about a new classification – or rather, a spectrum. Some viewfinders, I believe, are more life-like, by which I mean, the view is closer to what we see with the naked eye. Others are more photo-like, that is, the view more closely resembles the eventual photograph.

This post is the first in a two-part series about life-like and photo-like finders. In this part, I’ll talk about some common viewfinder designs, and how they can be arranged on a spectrum ranging from the “most life-like” to the “most photo-like” (let’s call this the L–P spectrum, for short).

In part 2, I’ll discuss some of the pros and cons of life-like versus photo-like finders. I’m less interested in the technical aspects – magnification, resolution, and so forth. Rather, I want to focus on something which is in a way simpler, but also harder to pin down. How does it feel to look through a life-like or photo-like finder? Does viewfinder design affect our relationship with the slice of the world that we perceive through the finder, and with photography in general? Can viewfinders help us to learn “how to see without a camera”?

But first, let’s define a viewfinder.

What is a viewfinder?

Wikipedia defines a viewfinder as “what the photographer looks through to compose, and, in many cases, to focus the picture.” For purposes of this post, I would add “looks through or at“, so as to include screens (both analogue ground-glass screens and LCDs).

Some cameras don’t have a finder at all. Examples include my homemade pinhole cameras, and the Mamiya Watcher A surveillance camera. Finder-less cameras, while obviously interesting, fall outside the L–P spectrum.

The L–P spectrum

The life-like/photo-like distinction is somewhat abstract and subjective. You may not agree with me as to where certain types of finders fall on this spectrum, or how I have grouped them together. That’s okay; I’m not trying to establish some objective ordering (yours may be different from mine). Nor am I suggesting that one finder type is somehow better than another. Rather, I am simply proposing a certain way of thinking about viewfinders. By reflecting on our choices – the types of finders available to us, and how they see the world – perhaps we can be better and more mindful photographers.

For each category of finder described below, I’ve included three basic details.

L–P rank: The most life-life finder, in my scheme, has an L–P rank of zero. The most photo-like has a rank of 5.

Position: For a given type of finder, this refers to how the camera is typically held. Some are designed to be used at eye-level or at waist-level. Others are flexible, like a modern LCD-equipped camera or smartphone.

Type of image: Some viewfinders, like those on a typical compact camera, form a virtual image. Others, like SLRs, TLRs and view cameras, form a real image which is projected on a ground-glass screen. Most digital cameras can display an electronic image, roughly corresponding to what the sensor “sees”.

Optic-less finders

| L–P rank | 0 |

| Position | Eye-level |

| Type of image | No image |

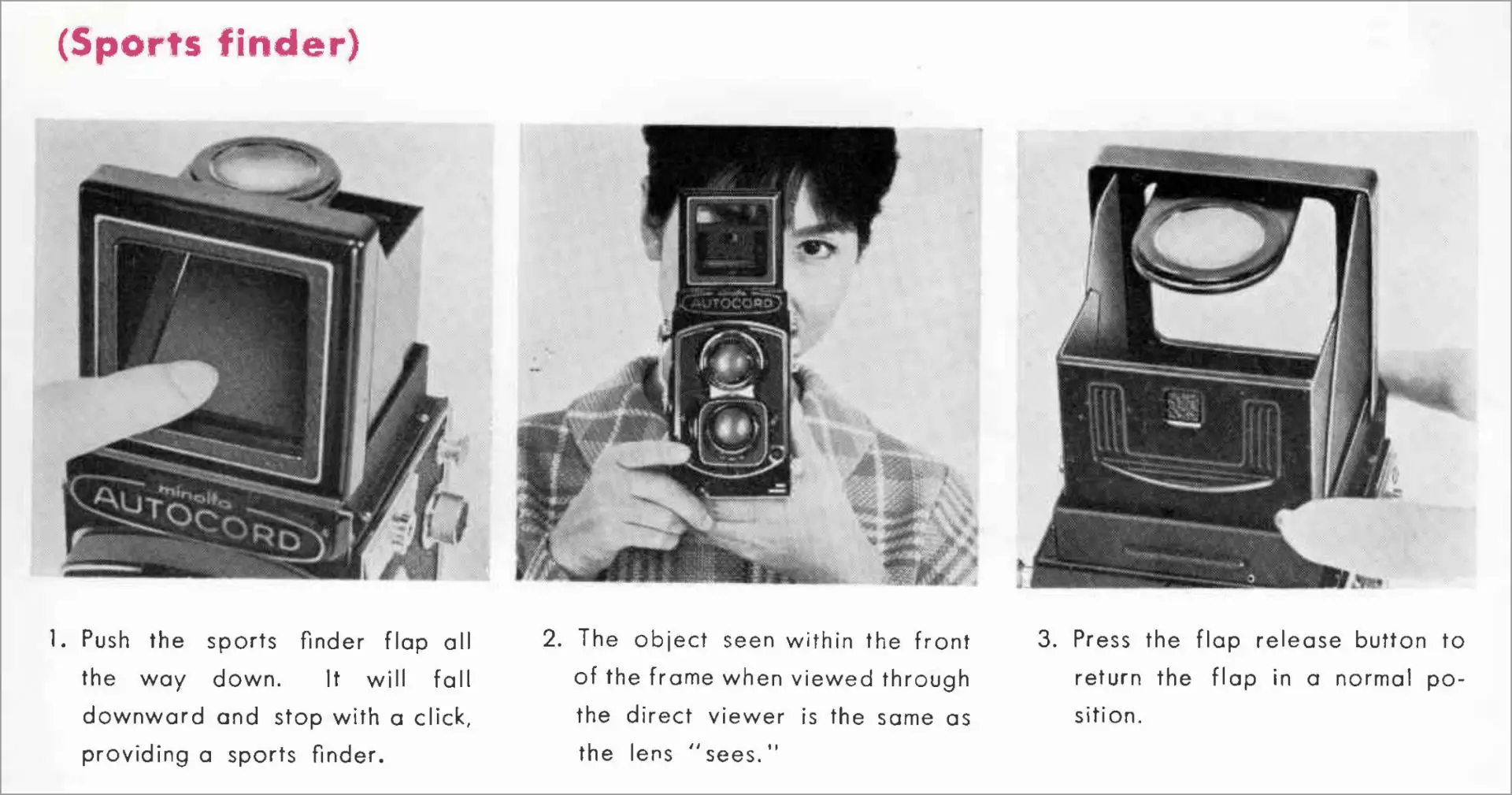

The most life-like finders are those which have no optics at all. These are called frame finders or sports finders. With optic-less finders, you simply look through a rectangular frame at the real scene, with no glass or other elements in the way. It doesn’t get more life-like than this – you are literally looking at the scene itself, with just a frame to mark the picture boundaries. A direct, unmediated view. Nothing between, just low-dispersion air.

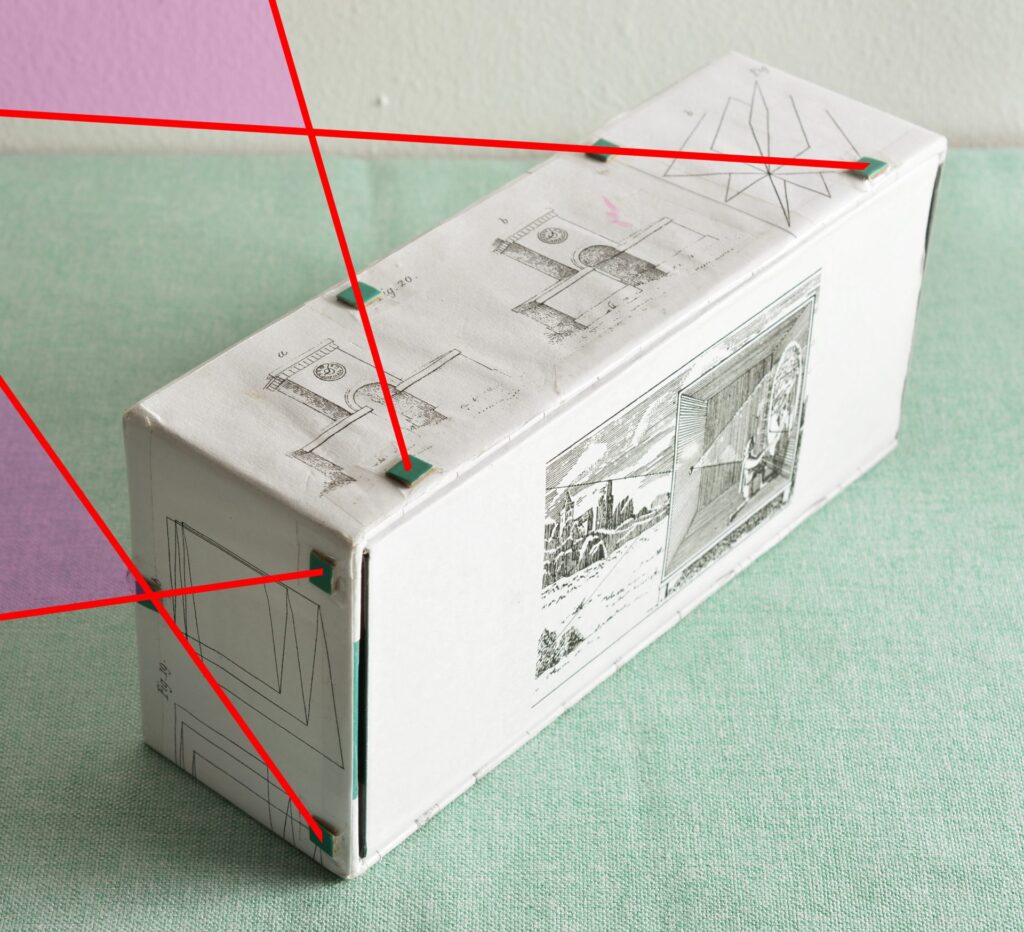

The Austrian Sport-Box is one example of a camera which only has a frame finder. The primary finder on my Minolta Autocord is the typical TLR ground glass, but it also sports (see what I did there) a sports finder.

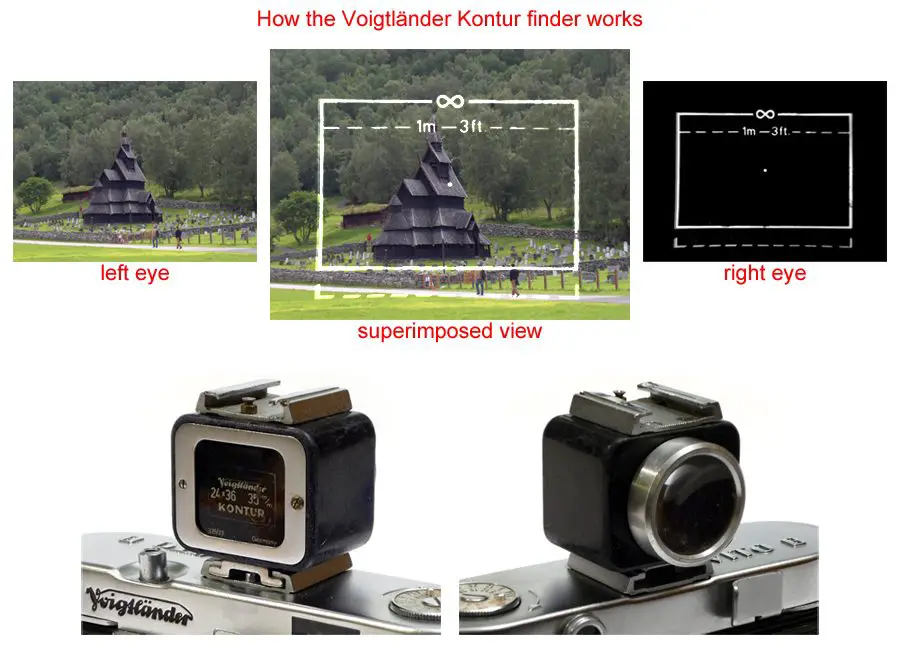

My favourite optic-less design is the Voigtländer Kontur accessory finder. The design is simple but utterly ingenious. You use it with both eyes open. One eye views the scene directly; the other eye looks through the finder which is otherwise dark, but has bright, projected framelines. Your brain superimposes the two, so that the framelines appear to float in your field of view.

Technically the Kontur does have an optic – a lens projecting the framelines at infinity. But that lens is only for the framelines; the view through the other eye is perfectly unmediated.

Direct optical finders

| L–P rank | 1 |

| Position | Eye-level |

| Type of image | Virtual image |

Direct optical finders are commonly found on compact and rangefinder cameras. Unlike an SLR, the image of the scene which reaches the photographer’s eye is not formed through the “taking lens”, i.e. the lens which forms the photographic image. Instead, the viewfinder is a separate, independent optical arrangement.

What optical arrangement? Now we’re getting nerdy. The most common design for direct optical finders is the reverse Galilean: a negative (diverging) lens in front, and a positive (converging) lens as the eyepiece.

More obscure direct optical finder designs include:

- Newtonian finders: a negative lens in front, and a simple targeting aid near the user’s eye, like on the Plate Tenax; and

- Keplerian finders aka astronomical finders: two positive lenses which come to a common focus at a point between them, often with a prism to erect the image, like on the Canon Demi, Kowa SW and Leitz VIDOM accessory finder (1932).

But these two are marginal cases. Most direct optical finders are of the reverse Galilean type, ranging from the simple two-lens affairs on toy cameras, to more complicated finders which incorporate features like rangefinder focusing aids, projected framelines and parallax compensation.

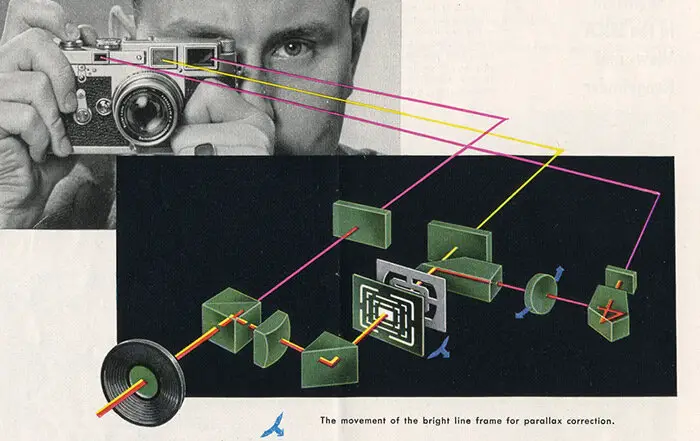

Just how complicated can you get? In his excellent article, Looking Forward: The Development of the Eye Level Viewfinder, Rick Oleson writes:

“The first viewfinder to combine automatic parallax compensation, projected framelines, and a rangefinder into a single optical system proved to be the high water mark in viewfinder development. Even now, 33 years after its introduction (note: this article was originally written in 1987), no optical viewfinder has surpassed in complexity of design, in versatility, in precision, or in ease of use, the system which appeared on the Leica M3 in 1954. Leitz solved Argus’ optical dilemma by building a complete astronomical telescope into the rangefinder assembly.”

Regardless of these variations, direct optical finders – whether on a toy camera or a Leica M3 – have one thing in common: the entire image is in focus. This is similar to how we perceive the world with the naked eye. (In reality, not everything is in focus at the same time, but our eyes rapidly change focus while scanning objects at different distances, creating the impression of an overall in-focus scene.) For this reason, I find direct optical finders to be more life-like – that is, closer to what the human eye sees – compared to, say, SLR or TLR finders.

Eye-level SLR finders

| L–P rank | 2 |

| Position | Eye-level |

| Type of image | Projected on a screen |

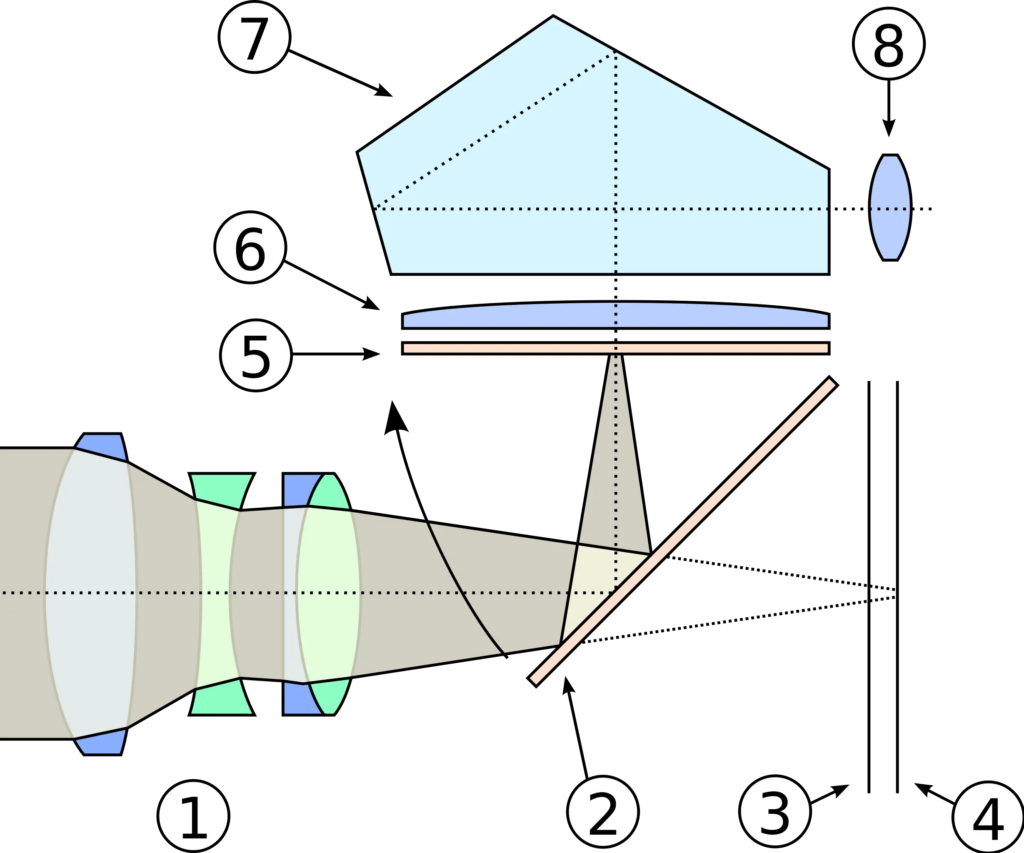

With a typical SLR, the photographer sees through the taking lens itself. Light from the lens is reflected up (or sideways if you’re using an Olympus Pen), forming an image on a matte focusing screen. That image is then righted by a pentaprism (or pentamirror) and seen through the eye-piece. The resulting image is thus almost identical to what the lens sees (but not exactly, since most SLR finders have less than 100% coverage).

With SLRs, we generally focus and compose with the aperture fully open. This produces a brighter image, and makes it easier to achieve accurate focus. But it also means that unlike a direct optical finder, an SLR finder has selective focus. With a fast lens, the depth-of-field (DoF) can be very shallow indeed. In that sense, the image seen through an SLR finder feels less life-like – at least to me – compared to a direct optical finder.

In an SLR finder, the plane of focus depends on how you turn the focus ring. Our eye can’t flit freely between objects which are closer and further away, adjusting focus on the fly, as we do in real life – or when looking through a direct optical finder.

So is an SLR finder “photo-like” than a direct optical finder? I think it is. If you shoot at wide apertures, the photo will have shallow DoF, just like the SLR viewfinder image. If you stop down, the photo will have more depth – but this too can be approximated on some SLR finders with the DoF preview function.

The SLR finder is also more faithful to focal length – the finder’s angle of view gets wider or narrower depending on the lens which is mounted on the camera (or if you zoom out or in). Direct optical finders, by contrast, typically show the same view, regardless of lens choice. (Interchangeable-lens rangefinders, like the Leica M series, have adjustable framelines, but the overall field of view does not change. Some direct optical finders, like the Canon VI and Contax G series, have adjustable magnification or “zoom” features, but these are the exception rather than the rule.)

Ground-glass screens

| L–P rank | 3 |

| Position | Waist-level or flexible |

| Type of image | Projected on a screen |

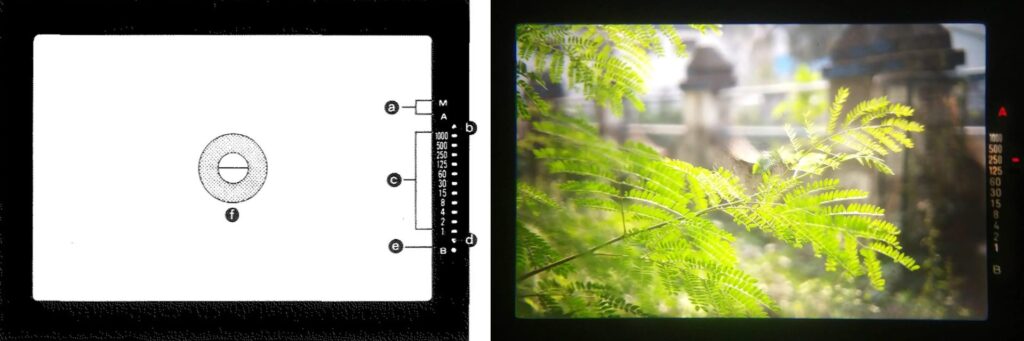

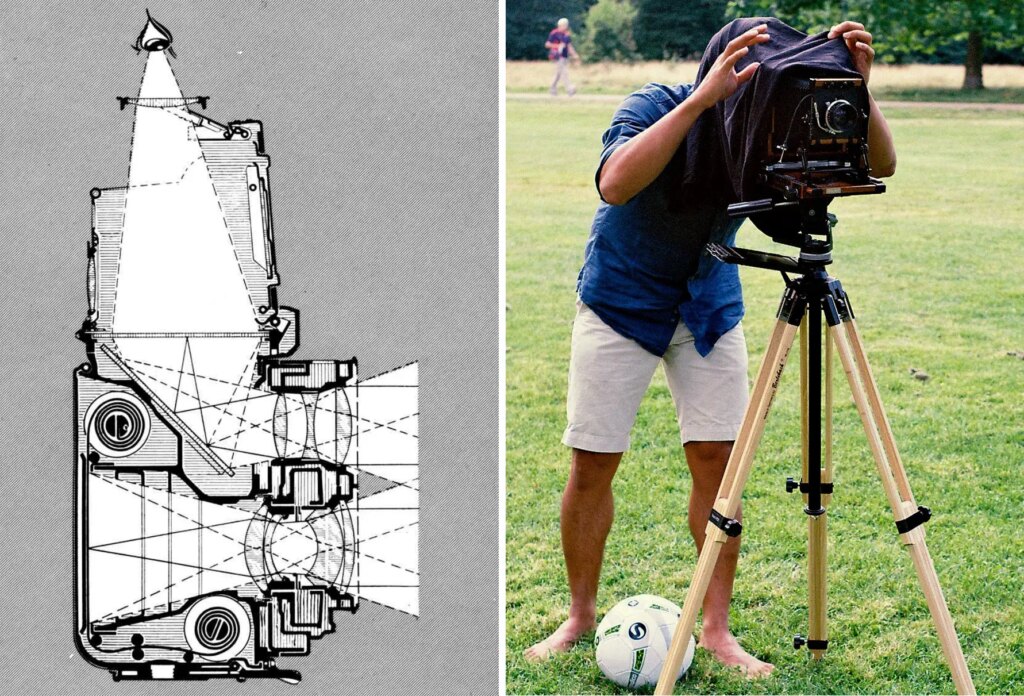

There are at least three distinct camera types which use ground-glass screens for composition and focusing: view cameras, TLRs, and SLRs with waist-level finders.

The actual mechanics of light propagation are all different. In view cameras, the taking lens forms an image directly on the ground glass. In reflex cameras, the image is formed by a separate viewing lens (TLRs) or by the taking lens itself (SLRs), reflected by a mirror, and then projected onto a focusing screen. As such, it may seem strange to lump all three together, but I think they occupy roughly the same space on the L–P spectrum.

Ground-glass screens – like eye-level SLR finders (see above) – have selective focus, which is a photo-like feature. Likewise, the finder image is formed through the taking lens (or in case of TLRs, through a lens very similar to the taking lens), so it closely approximates the angle of view. But to me, a ground-glass screen is even more photo-like than an eye-level SLR finder, because the ground glass is patently a two-dimensional object.

It’s true that with eye-level SLR finders, we are technically looking at an image projected on a ground-glass screen. But since we’re looking through an eye-piece (not at a screen), to me it feels more three-dimensional (and therefore less photo-like) than looking directly at the ground-glass screen itself.

Of course, the image on a ground-glass screen is inverted – laterally for SLRs and TLRs, both laterally and vertically for view cameras. But with practice, at least in my experience, the brain just “corrects” for it, and I don’t think the inversion makes them any less photo-like.

Electronic finders

| L–P rank | 4 |

| Position | Eye-level (EVF) or flexible (LCD) |

| Type of image | Electronic |

Electronic viewfinders (EVFs) and live-view screens (LCDs) – which I’ll collectively refer to as electronic finders – show roughly what the sensor sees. I say roughly because “what the sensor sees” is a philosophical question (electrical pulses? zeroes and ones?) Moreover, a RAW capture will have more information than what we see in the electronic finder (the latter is like a JPEG rendition). And of course, flash, long exposure and other “tricks” can result in a photo that is very different from the finder image.

But for practical purposes, electronic finders are extremely photo-like – effectively a preview of the photo itself. Exposure compensation can be visualised in real time, with the image getting brighter or dimmer. In B&W mode, the finder shows us a B&W image, achieving what analogue-era photographers tried to do with Wratten #90 filters. Their photo-like nature is especially evident in low light, where the EVF image can be much brighter than “real life”. At least with current technology, it doesn’t get more photo-like than this.

Or does it?

Phone screens

| L–P rank | 5 |

| Position | Flexible |

| Type of image | Electronic |

A phone screen is of course a type of electronic display, but I place it in a different category because for me, it is even more photo-like than an LCD on a dedicated camera. This is because, for the first time in the history of photography, the “viewfinder” is often the same device as the one on which the photo will eventually be viewed.

I took this photo backstage in a Teochew (traditional Chinese) opera production in Singapore. The actor’s assistant is taking a phone pic.

…and a few minutes later, they are looking at the photo on the same device.

For much of the history of photography, there has been a marked difference between the preview and the display. The difference was both temporal (an interval, sometimes weeks or months, between seeing an image through a finder, and eventually as a print) as well as material (the viewfinder was a fundamentally different object from the print).

The advent of instant film narrowed the temporal gap, and digital photography – with LCDs and instant playback – narrowed it even further. Suddenly, the interval between the preview and the final image (on the LCD) was down to a split second. However, the material difference remained. The LCD is good for chimping, but typically, photographs made with digital cameras are subsequently viewed on other devices, or as prints.

But most phone pics, I suspect, are also viewed on phones – whether on the same phone or, after being shared electronically, on other phones. The material difference has also collapsed. The viewfinder-device and the display-device are one and the same; the snake has swallowed its tail. In that sense, the phone-screen is the most photo-like finder of all.

Miscellaneous finders

In the classification above, I tried to include the most common viewfinder designs from past and present. I’m not trying to make an exhaustive list here, but there are a few other designs which I thought are worth talking about. I included them under “miscellaneous” because the first two are rather obscure, and the third, as far as I know, is only produced by one camera manufacturer.

The brilliant finder – see photos on this page, and the diagram here – is basically a Kepplerian finder (described above), but with a mirror in the optical path deflecting the image by 90°. The Sellar finder – photos and diagram here – is essentially a concave mirror. The brilliant and Sellar finder are both operated at waist-level, but like a direct optical finder (and unlike a TLR), all parts of the image appear to be in focus.

The other type of viewfinder worth mentioning is the revolutionary hybrid finder found on Fuji X100 and X-Pro series cameras (see this page for an overview of some of the design decisions that went into the hybrid finder, and this page to get a sense of what it’s like to look through it). As far as I know, the Fuji X100 and X-Pro series are the only cameras ever to combine an optical finder (L–P rank: 1) and an electronic finder (L–P rank: 4) in the same finder system, allowing the photographer to choose which one they want to use at any given time.

Summing up

Traditionally, viewfinders are classified based on how they work – the underlying technology. But we can also classify finders on a more subjective (or even philosophical) basis, namely whether they are “life-like” or “photo-like”. This article – the first of a two-part series – was an overview of some common viewfinder types, and where they fall on the L–P spectrum.

This classification, as I said, is somewhat subjective. You might think, for example, that an SLR finder is more life-like than a direct optical finder – and that’s fine by me. Nor do I wish to suggest that certain types of finders are objectively better than others. (Do you like some more than others? Let us know in the comments!)

Rather, what is more interesting to me is how life-like or photo-like finders affect our experience of photography, and how we see the world. And that’s something I’ll elaborate on in Part 2 of this series.

Thanks for reading. For more of my work, feel free to check out my Instagram.

References:

- R. A. Oleson, Looking Forward: The Development of the Eye Level Viewfinder

- Rudolf Kingslake, Lenses in Photography (1951)

- Sidney F. Ray, Applied Photographic Optics (2002)

- Mike Johnston, Understanding Viewfinders

- Camera-wiki: Viewfinder

- Wikipedia: Viewfinder

Share this post:

Comments

Bill Brown on Life-like Finders and Photo-like Finders Part 1: The L–P spectrum

Comment posted: 26/12/2023

Your article discusses more details about viewfinders than I've ever personally researched in my 40 years of shooting. I've just always accepted the finder as part and parcel with whatever camera I want to shoot with. Although, the sports finder option for my F1-n did influence my decision to buy that camera in 1984. I haven't shot with as many different cameras as you so maybe that affects my opinion here. I've never been into the technical specs of my cameras, just does it do what I'm looking for and how seamlessly does it mesh with my shooting style. That's my two cents worth.

Comment posted: 26/12/2023

Wouter Willemse on Life-like Finders and Photo-like Finders Part 1: The L–P spectrum

Comment posted: 27/12/2023

Also appreciate any resistance against that default forum answer that the camera doesn't matter. It's such nonsens. The way a camera fits your hands, whether its controls are easy to reach and operate, the viewfinder, the way to focus - it all does matter. Acting like you can ignore all that would (to me anyway) remove a vital part of the photo-making process. Part of the fun is operating the camera. Using a camera you don't like because it doesn't fit you will certainly have an effect on your photography... as you'll stop doing it. So, yes, the camera does matter :-)

Comment posted: 27/12/2023

rajat Srivastava on Life-like Finders and Photo-like Finders Part 1: The L–P spectrum

Comment posted: 27/12/2023

Comment posted: 27/12/2023

Simon Cygielski on Life-like Finders and Photo-like Finders Part 1: The L–P spectrum

Comment posted: 04/01/2024

I'm pretty sure AA's comment referred to the photographer's head, not the viewfinder.

Cheers,

S.

Sroyon on Life-like Finders and Photo-like Finders Part 1: The L–P spectrum

Comment posted: 09/01/2024